“Oh, there are some good ones among the bad. Hard to find, it’s true, but they are there.”

I shook my head. I kept seeing my father—why did I have to go on calling him my father?—I kept seeing Robert Tressidor cowering in that bed.

“It upset him terribly,” went on Rosie. “I reckon it killed him really. He had that first stroke soon after that. He must have been almost out of his mind … when he thought what it could mean. I wouldn’t have gone that far, though. I reckon I’ve been paid fair and square. Didn’t stop him changing that rotten will about you, though, did it?”

I shook my head. “Why should it?”

“Oh, he was very pompous and sanctimonious about your mother. We heard quite a bit when that little thing was going on. Such a great good man with such a naughty wife! How could she? And all the time there was sir, going to Crawley’s for a little bit of slap and tickle on the sly.”

“It’s so horrible,” I said.

“Do you think I’m awful?”

“No.”

“A woman who sells her body, who’s not averse to a little blackmail?”

“I’m glad you got something out of him, Rosie. It’s the hypocrisy, the deceit, I can’t bear. You were never like that.”

“Open as the day, that’s me. Well, I had to leave that night, you see. That’s why I wasn’t there to let you in. I had to pack up and be right out of the house by the time he came back. It was part of the bargain.”

“I understand, Rosie.”

“It took me a long time to decide whether to tell you or not. Then I heard you were going to France. How did I know? Servants! They talk. I mix a bit on the edge of society, too. There’s gossip. They were all talking about you being cut out and not his daughter and all that. That’s common knowledge. And I thought, ‘Poor Caroline. She’s got a hard row to hoe.’ And I thought I’d ask you to come and I’d tell you this. If ever you wanted a friend, Rosie’s here to help you. I’d ask you to stay here, but that wouldn’t be right for you. I do have the occasional gentleman friend … my own choice though this time. And I’ve got a bit of a reputation. One of these days I might settle down. I saw a little fellow the other day playing in the Park with his nanny. I thought … I dunno, there’s something about kids. Who knows, your old friend Rosie might fall for that lark one day. And when, and if, I do, I’ll have the right sort of place to bring it up. There! But remember this, if ever you think I could be of any help to you, you know where I am.”

“Thank you, Rosie,” I said.

She rang for the tea to be cleared away. I watched her with faint amusement mingled with awe.

She was a very clever woman, and in spite of the fact that she had been a part-time prostitute and was confessedly a blackmailer, she seemed to me to be a better human being than quite a number I could name.

I made my way thoughtfully back to the house.

Yes indeed, I was growing up fast.

NIGHT IN THE MOUNTAINS

I had come to Paris with the Rushtons as we had arranged, and they had very kindly seen me onto the train which was to make its journey to the South of France.

It was difficult to believe that so much was happening to me. The journey did not bother me. Going away to school had given me a certain self-reliance, and this was not my first visit to France, although I was scarcely a seasoned traveller.

As I looked out of the train window I kept telling myself that I must put behind me all that had happened. I must start a fresh life. I might well discover that my true place was with my parents. I was romancing again.

I think what had shocked me almost as much as the knowledge that it was not me but my inheritance that Jeremy had wanted, was what I had just heard of the man whom I had believed to be my father. I could not keep out of my mind the picture of him on that bed. I could understand his need for sexual satisfaction but not his hypocrisy. How could he make those speeches about fallen women when he himself was indulging in the practices he pretended to deplore?

“There’s lots like him,” Rosie had said, and Rosie knew men.

And Jeremy? I would never forget opening that letter and realizing that I had been living in a fantasy world.

But it was over. I had to start again.

And here I was speeding through the French countryside …past farms, buildings, fields, rivers, hills. At least I was going to my mother and she wanted to see me. I thought of Captain Carmichael. He would be with her, I supposed, and the thought of that cheered me. I had been fascinated by him when I was young, and not at all displeased to discover that he was my father.

It seemed a long journey. Miss Bell would have said: “France is a big country, much bigger than our own.” I smiled fleetingly. Miss Bell would have known the exact proportions.

That was long ago—in the past. I had to turn my back on all that life—stop thinking of it, because when I did I could only see those two deceivers—Jeremy Brandon and Robert Tressidor.

When I arrived at the station and left the train a trap was waiting for me.

I was told that Madame Tressidor was expecting me, and that the journey was not very long.

My fluent French was a great help to me, and my driver was delighted that I could speak the language. He pointed out the line of mountains in the distance and told me that beyond them was the sea.

We stopped before a house. It was white—neither big nor very small. There were balconies at two of the windows in the front and bougainvillea made a colourful purple splash against the walls.

As I alighted a woman came out of the house.

“Everton!” I cried.

“Welcome, Miss Caroline,” she said.

I took her hand and in my excitement would have kissed her, but Everton drew back, reminding me of her place.

“Madame is glad that you were coming,” she said. “This isn’t one of her good days … but she wants to see you as soon as you arrive.”

“Oh,” I said, feeling a little deflated. I had expected my mother or Captain Carmichael to be waiting to greet me, though I was glad, of course, to see the familiar Everton.

“Come on in, Miss Caroline. Oh, there’s your baggage.”

The driver helped carry it into a tiled hall.

I thanked him, gave him some coins, and he touched his cap. Everton was coolly aloof.

There was a bowl of flowers on the table in the hall and their pungent scent hung in the air.

“This is a very small establishment,” Everton explained. “We only have one domestique—as they call them here—and a man for the garden twice a week. You’ll find it very different from …”

“Yes, I suppose so. May I see my mother now?”

“Yes, come up.”

I was taken up a staircase and into a room. The shutters were closed and it was dark.

“Miss Caroline is here,” said Everton. “I’ll open the shutters, shall I, just a little?”

“Oh yes. And are you really there, my darling? Oh, Caroline!”

“Mama!” I cried, and running to the bed threw myself into her arms.

“My dear child, it is wonderful to see you. But you will find everything here … so different.”

“You’re here and I’m here,” I said. “I like the difference.”

“It is so wonderful that you are here.”

Everton went quietly to the door. She looked at me for a moment and said: “You must not tire her.” Then she went out.

“Mama,” I said, “are you ill?”

“My dear, let us not talk of unpleasant things. Here you are and you are going to stay with me for a while. You can’t imagine how I have longed to see you.”

I thought: Then why didn’t you make an effort to do so? But I said nothing.

“I used to say to Everton, if only I could see my girls … Caroline particularly. Of course, you see how I live now … in penury.”

“I thought it seems a very pleasant house. The flowers are lovely.”

“I’m so poor, Caroline. I could never really adjust myself to poverty. Did you know we have only one domestique and one gardener … and not full time at that.”

“I know, Everton told me. But you have her.”

“How could I do without her?”

“Apparently you don’t have to. She seems as devoted as ever.”

“She’s a bit of a tyrant. Good servants often are. She treats me as though I’m a baby. Of course, I suffer quite a lot. There is so much I miss. This is not London, Caroline.”

“That is obvious.”

“When you think of what life was before …”

“Mama,” I said, “what of Captain Carmichael?”

“Oh Jock … poor Jock. He couldn’t stand it, you know. It was idyllic in the beginning. We didn’t seem to mind the poverty at first. We neither of us had been used to it, you know.”

“But you were in love. You had each other.”

“Oh yes. We were in love. But there was nothing to do here. For me … nothing. For him, too. No racing. He loved the races. And then, of course, there was his career … the Army.”

“He gave all that up … for you.”

“Yes. It was sweet of him. And for a while it was wonderful … even here. Your father … I mean my husband … so vindictive. You know all about that now, I gather, from Mr. Cheviot. He’s been a good friend. He looked after everything, you know. He sends the money regularly. I don’t know what I should do without that. My income from my father is infinitesimal. Jock had very little apart from his soldier’s pay, and you know, that’s not much. He was always in debt. No one should attempt to hold a commission in the Queen’s regiments unless he has a good income.”

“But what happened? Where is he now?”

She took a lace handkerchief from under her pillow and held it to her eyes. “He’s gone. He died. It was in India. It was some awful disease he caught there. He had to resign his commission, you see. Poor darling, it was all because of the scandal, you know. He went out there. He was going into some sort of business with people he knew. He was going to make a lot of money and come back to me. But the Army was the only thing he really wanted to do. The Carmichaels were all soldiers. He’d been brought up to it. But he used to say it was all worth while … in the beginning.”

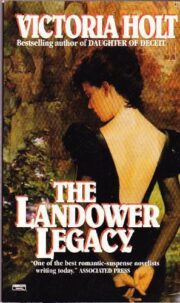

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.