I wished it were always like that. It occurred to me how different life would have been if we had had someone like Captain Carmichael for a father.

He was a most exciting man. He had travelled the world. He had been in the Sudan with General Gordon and was actually in Khartoum during the siege. He told us stories about it. He talked vividly; he made us see the hardships, the fear, the determination—though I suppose he skirted the real truth as too horrible for our youthful ears.

When tea was over he rose and my mother said: “You mustn’t run away now, Captain. Why don’t you stay the night? You could go first thing in the morning.”

He hesitated for a while, his eyes bubbling over with what could have been mischief.

“Well … perhaps I might play truant.”

“Oh, good. That’s wonderful. Darlings, go and tell them to prepare a room for Captain Carmichael … or perhaps I’ll go. Come along, Captain. I am so glad you came.”

We sat on—Olivia and I—bemused by the fascinating gentleman.

The next morning we all went riding together. My mother was with us and we were all very merry. The Captain rode beside me. He told me I sat a horse like a rider.

“Well, anyone is a rider who rides a horse,” I replied, argumentative even in my bliss.

“Some are sacks of potatoes—others are riders.”

That seemed to me incredibly funny and I laughed immoderately.

“You seem to be making a success with Caroline, Captain,” said my mother.

“She laughs at my jokes. The nearest way to a man’s heart, they say.”

“I thought the quickest way was to feed him.”

“Appreciation of one’s wit comes first. Come, Caroline, I’ll race you to the woods.”

It was wonderful to ride beside him with the wind in my face. He kept glancing at me and smiling, as though he liked me very much.

We went into the paddock because he said he would like to see how we jumped. So we showed him what our riding master had taught us recently. I knew I did a great deal better than Olivia, who was always nervous and nearly came off at one of the jumps.

Captain Carmichael and my mother applauded and they were both looking at me.

“I hope you are going to stay for a long while,” I said to the Captain.

“Alas! Alas!” he said, and, looking at my mother, raised his shoulders.

“Another night perhaps?” she suggested.

He stayed two nights and just before he left my mother sent for me. She was in her little sitting room and with her was Captain Carmichael.

He said: “I have to go soon, Caroline. I have to say goodbye.”

He put his hands on my shoulders and looked at me for a few seconds. Then he held me against him and kissed the top of my head.

He released me and went on: “I want to give you something, Caroline, to remember me by.”

“Oh, I shan’t forget you.”

“I know. But a little token, eh?”

Then he brought out the locket. It was on a gold chain. He said: “Open it.”

I fumbled with it and he took it from me. The locket sprang open and there was a beautiful miniature of him. It was tiny but so exquisitely done that his features were clear and there was no doubt that it was Captain Carmichael.

“But it’s lovely!” I cried, looking from him to my mother.

They both looked at me somewhat emotionally and then at each other.

My mother said practically: “I shouldn’t show it to anyone if I were you … not even Olivia.”

Oh, I thought. So Olivia is not getting a present. They thought she might be jealous.

“I should put it away until you’re older,” said my mother.

I nodded.

“Thank you,” I murmured. “Thank you very much.”

He put his arms about me and kissed me.

That afternoon we said goodbye to him.

“I shall be back for the Jubilee,” he told my mother.

So that was how I received the locket. I loved it. I looked at it often. I could not bear to hide it away though, and it gave me added excitement because I had to keep it secret. I wore it every day under my bodice, and kept it under my pillow at night. I enjoyed it not only for its beauty, but because it was a secret thing, known only to myself, my mother and Captain Carmichael.

We came up to London on the fourteenth of June—that was a week before the great Jubilee day. Coming into London from the country was always exciting. We came in from the east side and the Tower of London always seemed to me like the bulwarks of the city. Grim, formidable, speaking of past tragedies, it always set me wondering about the people who had been imprisoned there long ago.

Then we would come into the city and on past Mr. Barry’s comparatively new Houses of Parliament, so magnificent beside the river, looking, deceptively, as though they had weathered the centuries almost as long as the great Tower itself.

I could never make up my mind which I loved more—London or the country. There was a cosiness about the country, where everything seemed orderly; there was a serenity, a peace, which was lacking in London. Of course Papa was rarely in the country and on those occasions when he came, I had to admit peace and serenity fled. There would be entertaining when he came, and Olivia and I had to keep well out of the way. So perhaps it was a matter of where Papa was that affected us so deeply.

But I was always excited to be returning to London, just as I was pleased to go back to the country.

This was a rather special return, for no sooner did we reach the metropolis than we were aware of the excitement which Miss Bell called “Jubilee Fever.”

The streets of the city were full of noisy people. I watched them with glee—all those people with their wares who rarely penetrated our part of London; they were there in full force in the city—the chairmender, who sat on the pavement mending cane chairs, the cats-meat man with his barrow full of revolting-looking horseflesh, the tinker, the umbrella mender, and the girl in the big paper bonnet carrying a basket full of paper flowers to be put in fireplaces during the summer months when there were no fires. Then there were the German bands which were beginning to appear frequently in the streets, playing popular songs of the musical halls. But what I chiefly noticed were the sellers of Jubilee fancies—mugs, hats, ornaments. “God Bless the Queen,” these proclaimed. Or “Fifty Glorious Years.”

It was invigorating, and I was glad we had left the country to become part of it.

There was excitement in the house too. Miss Bell said how fortunate we were to be subjects of such a Queen and we should remember the great Jubilee for the rest of our lives.

Rosie Rundall showed us a new dress she had for the occasion. It was white muslin covered in little lavender flowers; and she had a lavender straw hat to go with it.

“There’ll be high jinks,” she said, “and there is going to be as much fun for Rosie Rundall as for Her Gracious Majesty—more, I shouldn’t wonder.”

My mother seemed to have changed since that memorable time when Captain Carmichael had given me the locket. She was pleased to see us, she said. She hugged us and told us we were going to see the Jubilee procession with her. Wasn’t that exciting?

We agreed that it was.

“Shall we see the Queen?” asked Olivia.

“Of course, my dear. What sort of Jubilee would it be without her?”

We were caught up in the excitement.

“Your father,” said Miss Bell, “will have his duties on such a day. He will be at Court, of course?”

“Will he ride with the Queen?” asked Olivia.

I burst out laughing. “Even he is not important enough for that,” I said scornfully.

In the morning when we were at lessons with Miss Bell, my parents came up to the schoolroom. This was so unexpected that we were all dumbfounded—even Miss Bell, who rose to her feet, flushing slightly, murmuring: “Good morning, Sir. Good morning, Madam.”

Olivia and I had risen to our feet too and stood like statues, wondering what this visit meant.

Our father looked as though he were asking himself how such a magnificent person as he was could possibly have sired such offspring. There was a blot on my bodice. I always got carried away when writing and made myself untidy in the process. I felt my head jerk up. I expected I had put on my defiant look, which I invariably did, so Miss Bell said, when I was expecting criticism. I glanced at Olivia. She was pale and clearly nervous.

I felt a little angry. One person had no right to have that effect on others. I promised myself I would not allow him to frighten me.

He said: “Well, are you dumb?”

“Good morning, Papa,” we said in unison. “Good morning, Mama.”

My mother laughed lightly. “I shall take them to see the procession myself.”

He nodded. I think that meant approval.

My mother went on: “Both Clare Ponsonby and Delia Sanson have invited us. The procession will pass their doors and there will be an excellent view from their windows.”

“Indeed yes.” He looked at Miss Bell. Like myself, she was determined not to show how nervous he made her. She was, after all, a vicar’s daughter, and vicar’s families were always so respectable that daughters of such households were readily preferred by employers; she was also a lady of some spirit and she was not going to be cowed before her pupils.

“And what do you think of your pupils, eh, Miss Bell?”

“They are progressing very well,” said Miss Bell.

My mother said, again with that little laugh: “Miss Bell tells me that the girls are clever … in their different ways.”

“H’m.” He looked at Miss Bell quizzically, and it occurred to me that not to show fear was the way to behave in his presence. Most people showed it and then he became more and more godlike. I admired Miss Bell.

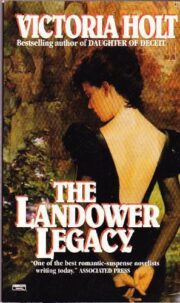

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.