“You’ve grown up now, Caroline,” she said, “and I know what’s happened. You’re not the heiress everyone thought you’d be. You’ve got a bit, but not much.”

“How do you know all this?”

“Gossip, dear. It was the talk of the town, wasn’t it? That great, good man dying … him who’d looked after all the Fallen Women.” She was consumed with laughter. “That’s the bit I like,” she went on. “And so he ought … considering he might on one or two occasions have tripped them up.”

“What do you mean, Rosie?”

“Well, I’m coming to that. I couldn’t have told you before … though I wanted to, on account of you thinking I might have let you down that night. You’re on your own now. You’re not one of the protected ones. You’ve got to know about things … life and all that. I figured that now all the wool should be pulled away from your eyes. You’ve got to look at what they call stark reality.”

“I agree with that. I’ve been a fool … ignorant … dreaming away … making everything look so lovely and quite different from what it really is.”

“That’s how most of us are, love, when we start out. But we’ve got to grow up and the sooner we start doing it the better for us. You remember when I was working at the house … the parlourmaid with a difference, eh? Well, the difference was that I didn’t want to be a parlourmaid all my life. I had plans and I had the face and the figure and the brains to make my ideas work. I had to be in London. I had to have somewhere to live. I had to be right in the center of things. So those nights … once a week … I used to go to Madam Crawley’s in Mayfair. It was a beautiful house, very pleasant … the most expensive in London … or one of them … and she wouldn’t take anybody. Now this might shock you a bit, but as I said you’ve got to face up to life. I used to go to Madam Crawley’s to, er … entertain gentlemen.”

She leaned back to look at me and I felt the colour slowly flow into my face.

“I see you understand,” she said. “Well, these things go on, and there’s all sorts in them … people you wouldn’t expect. Do you know I earned more in a few hours at Madam Crawley’s than I did in a whole year in service. I worked it out. I was once as innocent as you used to be. I’d been in service from the time I was fourteen. There was the master of the house who took a fancy to me. He seduced me. I was too frightened to say anything. And after that I met someone in a teashop and she told me how she went on and how she was saving to make a life for herself and perhaps get married and live decent ever after.”

“I understand, Rosie, I do.”

“I knew you would. There’s always rights and wrongs of any situation. Nothing’s all good … nothing’s all bad. I learned a lot, and I saved money … quite a tidy bit. I had plans to retire by the time I was thirty, say. Then I’d be very comfortable … but I had a windfall, and it’s that I want to tell you about.”

Coming in addition to everything else that had happened so recently this left me quite bemused. I should have guessed something like it of course … those evenings out, those fine clothes … everything pointed to it. But perhaps that was how it seemed now that I knew. I was sure no one else in the house had had any notion of how Rosie spent her nights out.

“I was doing very well,” she went on. “I had my nice nest-egg.

And then there was this night. Oh I could almost die of laughing thinking of it. Caroline, are you sure you understand … that you want me to go on?”

“Of course I do.”

“Well, you’re a big girl now. Cast your mind back to that night. There you were … all got up as Cleopatra. I was to open the door for Olivia and then nip round to the back and let you in. It was one of my nights out, remember? Well, as soon as you’d left for the ball I went out. I had to be back by eleven. Old Winch and Wilkinson were very sharp on that. They would have liked to stop my jaunts but I wasn’t having any of that. They didn’t want to get rid of me. I was a good parlourmaid. The mistress and master liked me to be seen by the guests. The right sort of parlourmaids are a very important part of a well-run household.”

“I know that, Rosie. Do get on.”

“Well, on that night when you were at the ball, I went to Crawley’s. Madam said, ‘There’s a rich gentleman coming tonight. One of our best clients. I’m glad your visit coincides with his.’ She shook her head at me and said, as she was always saying, ‘I could put such good business in your way, if you would live in.’ But I wasn’t for that. I wanted my freedom to come and go and once a week is all a girl needs at this sort of game. I had a beautiful silk dressing-gown which I used to receive my gentlemen in. There I was with nothing on but that and I went into the room where I found my gentleman. And there he was stark naked … lying on a bed waiting for me. I stared at him. Who do you think he was?”

“I can’t guess. Tell me.”

“Mr. Robert Ellis Tressidor, pioneer of good causes, saviour of fallen women, advocate for the poor unemployed.”

“Oh no! It couldn’t be.”

“Sure as I’m sitting here. He just sat up in bed and stared at me. I said, ‘Good evening, Mr. Tressidor.’ He couldn’t speak, he was so dumbfounded. His confusion was terrible. I even felt sorry for him. He was trembling. I doubt anyone’s ever been caught so red-handed, you might say. It was his face that was red. And I didn’t wonder at that. I reckon he could see the headlines in the paper. He said, ‘What are you doing here? You’re supposed to be a respectable parlourmaid.’ That sent me into hoots of laughter. ‘Me?’ I said. ‘It’s clear what I’m doing here, sir. The funny thing is what are you doing here, Mr. Protector of Fallen Women. Helping them to fall a bit farther?’ I was scared really and when I’m scared I always fight hard. Not for a moment did I doubt that he was in a worse position than I was. I was there in my dressing gown. All he had was the sheet to cover him up. It was the funniest thing I ever saw. Me … the parlourmaid standing there and him the high and mighty, one of God’s good men, lying naked on a bed.

“He calmed down a bit. He said, ‘Rosie, we shall have to sort this out.’ All very cajoling, equals now, none of the master and parlourmaid. He was a very frightened man. He said, ‘You shouldn’t be living this life, Rosie.’ ‘Should you, sir?’ I asked. ‘I admit,’ he replied, ‘to a certain weakness.’ That made me laugh. Then I saw the possibilities and I said, ‘I could make things very difficult for you, Mr. Tressidor.’ He didn’t deny it. I could see he was thinking … hard. It was in his eyes. Money, he was thinking. Money straightens out most things and he was right about that. ‘Rosie,’ he said. ‘I’ll make it worth your while.’ And I said, ‘Now you’re talking.’

“I can laugh now. Him in the bed there and me standing there in my dressing-gown—and we made terms. He wanted me out of the house. I understood that. He couldn’t have me there all the time reminding him. And he wanted me out at once. He would give me a large sum of money as the price of my silence. He became quite human in his fear, and, by God, Caroline, he was afraid. He could see what I could see. ‘Philanthropist Robert Tressidor discovered in a brothel …’ Well, we made an amicable arrangement. He would pay me well and I should leave at once. I should go to an hotel for the night … at his expense, of course, and stay there until something could be arranged for me. He owned a great deal of property in London and he would see what could be done about accommodation for me. He gave me all the money he had on him and promised to pay me a large sum. That would be an end of it. He had no intention of giving way to further blackmail. I did not want that either. It’s a dangerous game. All I wanted was a good start in life—just what some people get by being born into it and others have to fight for. He quite understood my desire to break away from a life of service—my ambition, he called it, and he had a great respect for ambition. After all he had a good deal of it himself. He was frank in a way, and do you know, I liked him better lying there in bed naked and being a bit humble … and in a way understanding … than I ever had the virtuous philanthropist. I said, ‘Look here, Mr. Tressidor, you play fair with me and I’ll play fair with you. I could expose you to the papers. There’s nothing they’d like better than that sort of scandal. You’d be ruined.’ He admitted this, and said that he would honour his promises to me. But I was clever enough to understand he would not endure perpetual blackmail. He would pay the initial amount but that must be the end of the matter. I agreed. I’m not a blackmailer by nature, but I’m a girl who has to fight, and when you’ve got all the odds against you, you can’t be over-nice. There! What do you think of that?”

“I can’t stop thinking of him … always pretending to be so good … the way he behaved to my mother. Is the world full of deceitful people?”

“Quite a large number of the population, I shouldn’t wonder. There! Was I right to tell you?”

“It’s always best to know everything.”

“You’ve got to fight through life as I have had to. It’s better to know people. The world is not always a pretty place. Oh, I reckon some go through and never see the seamy side. But look at your father … I mean Robert Tressidor. He was a man who had desires like most men. I know the sort. There were a lot of them like that at Crawley’s. They’re what they call sensual, and they can’t get what they want at home. They have to play the gentleman there and maybe are ashamed to do what they really want, so they go for girls like me. Then they can do what they like. They don’t have to worry about showing themselves for what they are. That’s what it’s all about.”

“I’m glad you told me, Rosie. I want to know everything. I never want to imagine things are not what they seem again. I think I hate men.”

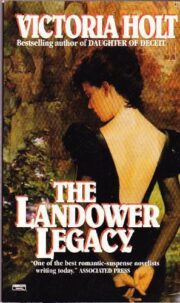

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.