“But even if I was not to be married he would still have left me with—what is it? Fifty pounds a year. Of course, he is such a good man. He has taken such care of all those philanthropic societies. It is no wonder that he cannot concern himself with his wife’s daughter.”

Mr. Cheviot looked pained. “I am afraid recriminations do not help the situation, Miss Tressidor. Well, I had my duty to perform and I have done that.”

“I understand that, Mr. Cheviot. I … I never thought of money before.” He did not speak, and I went on: “Do you know where my mother is?”

He hesitated and then said: “Yes. There have been occasions when it was necessary, when acting for your father, to be in touch with her. He had made her a small allowance which he considered his duty for in spite of her misdemeanours she was his wife.”

“And you will give me her address?”

“I can see no reason why it should be denied to you now.”

“I should like to see her. I haven’t done so since the time of the Jubilee. She has never written to me or my sister.”

“It was a condition of her receiving the allowance that she did not get in touch with you. Those were Mr. Tressidor’s terms.”

“I see.”

“I will have the address sent to you. She is in the south of France.”

“Thank you, Mr. Cheviot.”

When I left him I went straight to my room. Olivia came to me. She was very distressed.

“It’s terrible, Caroline,” she cried. “He has left me so much … and you nothing.”

I told her what the solicitor had told me. She listened wide-eyed.

“It can’t be true.”

“Don’t you remember how we went to Waterloo Place? It was my fault, Olivia. I blurted out that we’d been there. He saw the locket. Oh, you didn’t know about the locket. Captain Carmichael gave it to me. It had his picture in it. You see, it was his way of telling me he was my father.”

“It’s not the same between us, is it? We’re not the same sisters.”

“We’re half sisters, I suppose.”

“Oh, Caroline!” Her beautiful eyes were full of tears. “I can’t bear it. It’s so unfair to you.”

I said defiantly: “I don’t mind. I’m glad he wasn’t my father. I’d rather have Captain Carmichael than Robert Ellis Tressidor.”

“It was cruel of him,” said Olivia, and then stopped short, realizing she was speaking ill of the dead.

I said: “I shall get married … soon.”

“You can’t while we’re in mourning.”

“I shall not stay in mourning. After all, he is not my father.”

“It’s so … hateful.”

I laughed rather hysterically. “We always shared everything … governess … lessons … everything. Now you’re the heiress and I’m the penniless one … well, not exactly penniless. I have enough to stop myself starving, I suppose. And you Olivia, quite suddenly, have become a very rich woman.”

“Oh Caroline,” she cried, “I’ll share all I have with you. This is your home. I’ll always be your sister.”

We clung together, half laughing, half crying.

I had arranged to take another look at the bijou house with Jeremy and I decided that I would not let what had happened stand in the way of that.

Jeremy was strangely subdued. I supposed he was thinking of the funeral. I did not want to talk of it, I told him I wanted to look at the house and think about the future.

As soon as we opened the door and stepped inside he seemed to throw off his gloom. Hand in hand we went through the rooms; we discussed what we would turn them into, what colour carpets, what sort of curtains.

Then we went to the garden and stood under the pear tree, looking back at the house.

“It really is a gem,” said Jeremy. “I could have been so happy living here with you.”

“Well, we are going to,” I replied.

“How shall we pay for it, Caroline?”

“Pay for it. I hadn’t thought of that.”

“It’s customary when buying something to have to pay for it, you know.”

“But …” I looked at him in astonishment.

He said with some embarrassment: “You’ve always known I haven’t much. The allowance from my father is adequate … but this would require a lump sum.”

“Oh I see, you thought … like everyone else … that I should have some money.”

“I thought that your father would help us with the house. A sort of wedding present. My family would have come up with something but I know they could never afford to buy the house outright.”

“I see. We shall have to find something less expensive.”

He nodded solemnly.

“Oh well, never mind. Houses are not all that important. I’d be happy anywhere with you, Jeremy.”

He held me tightly in his arms and kissed me with growing passion.

I laughed. “Why are we looking at this house if we can’t afford it?”

“It’s nice to look at what might have been. Just for this afternoon I want to pretend that we are going to live here.”

“I want to get out of this house right away. I want to forget all about it. It’s rather old. It’s probably damp. And look at this tiny garden. One small pear tree. But it doesn’t have any pears on it and when it does they’ll be sour, I know. We’ll rent … chambers. Is that what they call them? Somewhere right on the roof tops … on the top of the world.”

“Oh,” he said, “I do love you, Caroline.”

I did not notice the regret in his voice.

It was two days later when I received the letter from him. I guessed it had taken him a long time to find the right words.

“My dearest Caroline,

“You will always be that for me. This is very hard for me to say, but I do not think it would be wise for us to marry. Love on the rooftops sounds delightful and it would be … for a time. But you would hate poverty. You have always lived in luxury and I have had enough. We should be so poor. My allowance and yours together … two people couldn’t live on it.

“The fact is, Caroline, I’m not in a position to marry … in the circumstances.

“This breaks my heart. I love you. I shall always love you. You will always be someone very special to me, but I know you will see that it is simply not practical to marry now.

“Your heartbroken

“Jeremy, who will love you till he dies.”

It was the end. He had jilted me. He had believed that because I was supposed to be the daughter of a very rich man he would be marrying an heiress.

He had been mistaken.

I felt my happy world collapsing about me.

His love for me had all been the greatest fantasy I had ever imagined. I did not weep. I was numb with wretchedness.

It was Olivia who comforted me. She kept assuring me that we should always be together. I must forget all that stupid talk about money. I was her sister. She would make me an allowance and I should marry Jeremy.

I laughed at that. I said I would never marry him. I would never marry anyone. “Oh, Olivia, I thought he loved me … and it was your father’s money that he wanted.”

“It wasn’t quite like that,” insisted Olivia.

“How was it then? I was ready to marry him … to be poor. He was the one who could not endure it. I never want to see him again. I have been foolish. I feel I’ve grown up suddenly. I shan’t believe anyone any more.”

“You mustn’t say that. You’ll grow away from it. You will. You will.”

Then I looked at her and I thought: “I believe she was in love with him. She didn’t say so. She let me go ahead … and discover what he was worth.”

“Oh, Olivia,” I cried. “My dear, sweet sister, what should I ever do without you?”

Then I found the tears came and I felt better for crying there with her.

But there was a terrible bitterness growing in my heart.

REVELATIONS OF AN INTIMATE NATURE

I had changed. I even looked different. I had grown up suddenly. There was a glitter in my eyes, which had become a more vivid green. I piled my hair on top of my head; it gave me height. I began to think about money—something I had never considered before. I was going to have to be very careful if I were to live on my income.

I noticed a change in the attitude of the servants towards me. There was less deference than there had once been. I remembered a time when Rosie Rundall had laughed over the protocol in the servants’ hall. The ranks of society there were more clearly defined and far more numerous than above stairs.

Now I was no longer in the position of daughter of the house. I was present more or less on sufferance. Respect for Olivia had increased a hundredfold. She would one day be mistress of the house.

This was for me a transient period—a time of decision. I would wake in the morning and say, “What are you going to do?” And then I would think of Jeremy Brandon and all I had hoped and planned. I had been so guileless, a foolish romantic girl who had never realized for one instance that when he saw our little home where we were to be so idyllically happy, he was seeing the fortune he expected me to inherit.

I was wretched. Sometimes I yearned for him; but at most times I hated him. I think my hatred was more fierce than my love had ever been. I had made a complete volte face. Previously I had seen the world peopled by gods and goddesses.

Now I saw it inhabited by deceitful, scheming people whose entire concern was to get what they could at the expense of others.

Olivia was the exception. She only was good and it was to her I continually turned for comfort, and she gave herself up entirely to the task of comforting me.

It did not matter that the money had been left to her, she insisted. It was ours. And as soon as it was hers she would give me half.

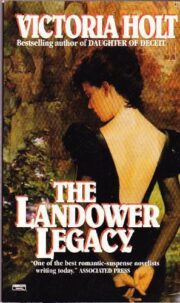

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.