It was not only with Moira that my stock had risen.

I was invited to several houses. I took tea at the Massinghams’ and Lady Massingham regarded me with approval. There were other mothers present. I was something of a phenomenon—the girl who had acquired a fiance without the cost of an enormously expensive season.

How I revelled in my glory.

I was sorry for Olivia, who after two years had failed to achieve what I had before starting.

Even Aunt Imogen deigned to notice me now.

“It is the best thing that could have happened,” she said. “The money your maternal grandfather left you is to be released. It is not much. There is a lump sum of a few hundred pounds, which was to come to you when you were twenty-one or on your marriage; and then you will have an income of fifty pounds a year. It is not a great deal. Your mother’s family were not rich.” She sniffed with a certain degree of elegance to indicate her contempt for my mother’s family. “The money will be useful and we can start to plan your trousseau. June is a good month for weddings.”

“Oh, but we don’t want to wait as long as that.”

“I think you should. You are very young. You have never been launched into society. It is most fortunate that this young man has offered to marry you.”

“He thinks he is rather fortunate,” I said complacently.

She turned away.

I thought: We are not going to wait until June. But when I broached the matter with Jeremy he said: “If that is what your family want we should go along with it.”

We looked at houses. What a happy day that was when we found the little house in a narrow street—one of the byways of Knightsbridge. The rooms were not large but it had an air of elegance. There were three storeys with three rooms on each floor and a small garden in which a pear tree grew. I knew I could be happy in such a house.

The servants regarded me with a new respect. Jeremy was allowed to call at the house and he and I could go out together on certain occasions. I lived in a whirl. I was in love; I had never been so happy in my life—and I believed it would go on like that for the rest of it.

Jeremy of course was not exactly the catch of the season. He had just scraped into the magic circle set up by what he called the Order of the Questing Mamas. It was through family connections rather than wealth, and to make the perfect catch a man must have both. But one, in certain circumstances, could be regarded as enough.

How we laughed together! The days seemed full of sunshine, though I did not notice the weather. The wind could blow; the rain could teem down; and life was still full of sunshine. We were constantly together and so delighted because my father had given his consent—not that we could not have surmounted that difficulty, said Jeremy; but it was better not to have to. I was mildly surprised how much store he set by that. He said that he did not want any impediments. He was passionate and irritated by the restraints which were put upon us. He told me how he longed for the time when we could be together all through the days and nights.

I lived in an enchanted dream until one morning when our household was thrown into confusion.

When my father’s manservant had gone to his room he found him dead. He had had another stroke—a massive one this time—and it had killed him.

Death is sobering—even that of people one has never really known. I suppose I could say I had never known my father; certainly there had been no demonstrative love between us, but he had been there in the house, though a figure who represented virtue and godliness. I had always imagined God was rather like my father. And now he was not there.

The Careys came at once and took over control. All the servants were in a state of tension, speculating as to what changes would be made in the household. There would certainly be some and they might well be out of employment.

Gloom pervaded the house. To smile would have been considered showing a lack of respect to the dead. Outside the house a funeral hatchment—a diamond-shaped tablet with the Tressidor armorial bearings—was fixed to a wall; and there were notices in the papers, besides his obituary which extolled his virtues and set out in detail the good works he had accomplished during a lifetime “devoted to the service of his fellow men.” He had been a selfless man, we were told. He was one of the greatest philanthropists of our age. Many societies working for the good of the community were grateful to him and there would be mourning all over England for the passing of a great good man.

Miss Bell cut out all the notices to preserve them for us, she said; and there was a great deal of activity over what was called “The Black.”

We all had to have new black garments and we should attend the funeral with veils over our faces. We should be in mourning for six months, which was the specified period for a parent; Aunt Imogen escaped with two months since she was a sister merely; but if I knew anything about her she would extend that period.

So Olivia and I should be in our black for six months and then, said Miss Bell, we should emerge gradually into greys perhaps. No bright colours for a whole year.

I said I couldn’t see why one couldn’t mourn just as sincerely in red as black.

Miss Bell said: “Show some respect, Caroline.”

Many of the servants were given black dresses and the men wore crepe armbands.

Everyone—not only in the house but in our circle—talked of the goodness of my father, of his selfless devotion to his philanthropic work which had never flagged even when he suffered ill health and domestic trials.

I was relieved when the day of the funeral arrived.

People gathered in the streets to watch the cortege, which was very impressive. I saw it through my veil which gave a hazy darkness to the scene. The horses magnificently caparisoned in their black velvet and plumes; the solemn black-clad men in their deep mourning clothes and shiny top hats; Olivia seated opposite me, looking white-faced and bewildered and Aunt Imogen upright, stern, now and then putting her black-edged handkerchief to her eyes to wipe away a tear which was not there, while her husband, seated beside her, contorted his face into the right expressions of grief.

And then to the family vault—grim and menacing with its dark entrance and its gargoyle-like figures defacing—rather than decorating —the marble.

I was glad to ride back to the house—far more quickly than we came. There were sherry and biscuits provided for the mourners, and all I guessed were waiting for what I was sure was for them the great event of the day—the reading of the will.

The family was present in the drawing room and Mr. Cheviot, the solicitor, was seated at a table with documents spread out before him.

I listened without paying a great deal of attention to the legacies for various people and the large sums of money which were to be put in trust for some of the societies in which my father was interested.

He expressed appreciation of his dear sister, Imogen Carey, and she was rewarded financially for her support. He was a very wealthy man and I gathered that Olivia would be a considerable heiress. I was surprised when Mr. Cheviot finished reading the will that I had not been mentioned. I was not the only one who was surprised. I was very much aware of the looks which were, somewhat furtively, cast in my direction.

Aunt Imogen came to me and said that Mr. Cheviot would like to see me alone as he had something very important to say to me.

When I sat facing him in that room which had been my father’s study, he looked at me very solemnly and said: “You must prepare yourself for a shock, Miss Tressidor. I have an unpleasant duty to perform and I greatly wish that it was not necessary for me to do so, but duty demands that I should.”

“Please tell me quickly what it is,” I begged.

“Although you have been known as the daughter of Mr. Robert Ellis Tressidor, that is not the case. It is true that you were born after your mother’s marriage to Mr. Tressidor, but your father is a Captain Carmichael.”

“Oh,” I said slowly. “I ought to have guessed.”

He looked at me oddly. He went on: “Your mother admitted that your father was this man, but not for some years after your birth.”

“It was at the time of the Jubilee.”

“June 1887,” said Mr. Cheviot. “It was at that time when your mother made a full confession.”

I nodded, remembering: the locket, my mother’s sudden departure, the manner in which he had ignored me. I could understand it now. He must have hated the sight of me because I was the living evidence of my mother’s infidelity.

“There was a separation at the time,” went on Mr. Cheviot. “Mr. Tressidor could have divorced your mother but he refrained from doing so.”

I said rather defiantly: “He would not have wanted the scandal … for himself.”

Mr. Cheviot bowed his head.

“Understandably he has left you nothing. But you will have a small inheritance from your mother’s father, who left this money in trust for you when you came of age, or on your marriage, or at any time the trustees should consider it should be passed to you. I am happy to tell you that in view of your sudden impoverishment, the money is to be released to you immediately.”

“Some of it has already been released.”

“Yes, that was at the request of Lady Carey.”

“It has been spent on my trousseau … or most of it has.”

“I understand you are shortly to be married. That is very satisfactory and will solve many difficulties, I do not doubt. Mr. Tressidor did say before he died that it was a solution for you who could not after all be blamed for the sins of your parents.”

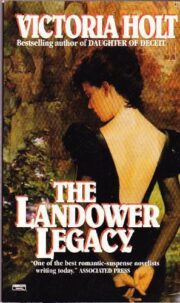

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.