Olivia began to laugh.

The next day she said: “I was talking to Moira Massingham at the Dentons’ place and she said you ought to go. Why not? she said. No one would know and you could be like Cinderella and slip away before the stroke of midnight and the unmasking.”

The idea appealed to me.

“But I would be an uninvited guest,” I said.

“Not if Moira knew. After all it’s for her. Surely she can ask her friends.”

The prospect of going to the masked ball added zest to the days. Moira Massingham was thrilled by the idea. It had to be secret. She visited us for tea, which we were allowed to have together and alone—a tribute to Olivia’s maturity—and I was not sure whether I was expected to be present, but I managed to be.

“It’s a shame you’re not ‘out,’ ” said Moira to me when Olivia had gone out of the room to get something she wanted to show to Moira. “Perhaps they want to get Olivia married off first and think you might spoil her chances.”

“Why ever should I?”

“Because you’re more attractive.”

“That hadn’t occurred to me.”

“Never mind. You’re coming to the ball.”

Olivia returned and I could not stop thinking of what Moira had said. I wondered if Olivia believed the same. Poor Olivia, she already had a notion that nobody found her attractive.

Getting me to the ball would need a certain amount of manoeuvring. If it were discovered, the project would immediately be stopped. The fact that Moira wanted me to go eased my conscience about gate crashing. But how was I to get out of the house in my finery without being noticed?

When Rosie Rundall heard of it—and we could not resist telling her—she immediately took over command. “It’ll be tricky,” she admitted, “but we’ll manage. Leave it to me.”

She decided that Thomas, the coachman, would have to be a collaborator.

“He’ll do it for me,” she said with a laugh. “He’s the only one who would be ready to risk his job because he knows he couldn’t easily be replaced. They wouldn’t find the mews in such good order if Thomas wasn’t there. He’ll help us.”

So it was arranged that I should go to the back door through a corridor which was not used very much, and out across the garden to the mews where Thomas would be waiting with the carriage. Rosie would see that the coast was clear. I should get into the carriage, cower back so that I could not be seen while Thomas brought the carriage round to the front door to pick up Olivia.

“Do you think Aunt Imogen will be going with Olivia?” I asked.

There was a problem. If she did go the whole plot would fail.

“I’ll make them see that the whole idea of a masked ball is that nobody knows who is who,” said the forceful Moira. “I’ll impress on my mother that chaperones must be excluded on this occasion. I’ll say we’ll only ask the girls who can take care of themselves. None of the starters, the just-out-brigade.”

We were all giggling at the prospect and gave ourselves up to the fun of planning.

“What will you go as, Caroline?” asked Moira, who was going as Lady Jane Grey.

“Oh, we’ve discussed that,” said Olivia. “Caroline thinks of the maddest things.”

“I rather fancy Boadicea.”

“You’d have to have a chariot.”

“I should love to ride in scattering all before me.”

“Talk sense,” said Moira.

“Diana the Huntress. That would be fun. Helen of Troy. Mary Queen of Scots.”

“Think of the costume.”

“None of those is impossible.”

We went through Olivia’s wardrobe. She had a beaded jacket with beads which reminded me of hieroglyphics. I tried it on and shook out my dark hair. I had come back to my original idea. I would be Cleopatra.

Moira clapped her hands. “It’s perfect,” she said. “With a long black skirt. Here it is. Try it on.”

She looked at me critically, her head on one side, and said she had a necklace which looked like a snake. It had belonged to her great-grandmother. “There is your asp.”

Excitedly we planned.

I was sure Olivia was more interested in my costume than her own, which Aunt Imogen had helped to create. She was to be Nell Gwynn with a basket of oranges as her badge of identity.

Thomas was eager to help—perhaps mainly to please Rosie. I think quite a number of servants thought I was badly treated and were eager to perform little services for me.

We were all waiting with the utmost eagerness for the night of the ball. Moira brought our masks. It was imperative that they should all be the same, she said. They were large and black and covered our faces so well that it would be difficult for anyone to recognize us.

Rosie tried on our dresses and would not have needed much persuasion, I felt, to come herself; but when I mentioned this she said: “Oh no, ducks. It’s one of my nights off. I’ve got my own fish to fry.”

The arrangement was that when we returned she should let me in by way of the back door. Olivia would be dropped at the front door, which would be opened by Rosie in her capacity of parlourmaid—for she must return from her own night out by eleven o’clock—and she was in fact to sit up to perform this duty. Then Thomas would drive me round to the mews. I would then cross the garden to the back door where Rosie would be waiting to let me in, making sure that I was not seen.

The evening came. We were on the alert all the time while Olivia helped me to dress. She had taken the precaution of locking the door. Finally I was ready in my beaded hieroglyphics and my snake necklace. My hair, which had been dressed by Olivia, fell over my shoulders. I wore a headdress which we had contrived from stiff cardboard, painted red, blue and gold. It looked most effective, and I believe I did bear a resemblance—if a faint one—to the celebrated Queen of Egypt.

The dangerous moment had come, which was to get me out of the house undetected. We had eluded Aunt Imogen and Miss Bell; but the most perilous moments lay ahead, and I do not know what we should have done without Rosie. She it was who made sure that all was safe, and I crept out of the house to the mews where Thomas was waiting with the air of a conspirator. He bundled me into the carriage.

“Crouch down, Miss Caroline,” he said. “My, you’ll be the belle of the ball. What you supposed to be?”

“Cleopatra.”

“Who’s she when she’s out?” Thomas prided himself on his modernity and had all the catch-phrases of the day on his tongue.

“She was a Queen of Egypt.”

“Well, you’ll be queen of the ball, Miss Caroline, and that’s nearer than Egypt, eh?”

He laughed immoderately. Another of Thomas’s characteristics was to laugh heartily at what he considered his jokes. The trouble was that no one else saw them in that light.

“Now keep out of sight,” he warned. “Otherwise we’ll be in trouble, and Miss Rundall wouldn’t like that at all, would she? I’d be in the doghouse, I can tell you.”

We came round to the front of the house and Thomas leaped down to make sure that no one helped Olivia into the carriage but himself. Rosie stood at the door watching, all dressed in her night-out finery, and ready to set off for the frying of that fish she had mentioned. Olivia hurried into the carriage, nearly dropping her oranges, overcome as she was with excitement and nervousness.

Then we were trotting along to the Massinghams’.

Theirs was a large, imposing residence backing onto the Park, and carriages were already lining up at the door while their masked occupants alighted. Passers-by watched with amusement as we went into the house.

There was no formal greeting for the whole idea was that nobody knew who anyone else was.

“Ten minutes to midnight,” said Olivia warningly, as we left the carriage. “No later, Thomas.”

Thomas touched his cap. “I know, Miss Olivia. Before they take off their masks, eh? Wouldn’t do for anyone to see who’s who.” He was overcome with amusement.

“That’s the idea, Thomas,” I said.

“Well, ladies, I hope you enjoy it. You can rely on old Thomas to get you back.”

He went off chuckling and Olivia and I went to the ball.

The salon was on the first floor and it made a sizeable ballroom. It looked very grand decorated with flowers, and the musicians were playing as we entered. From the windows I could see the garden below— looking very romantic in moonlight. White chairs and tables had been set up down there, and beyond, the Park looked like a mysterious forest. I caught a glimpse of silver through the trees and guessed that to be the Serpentine.

I kept close to Olivia. Two men came up. One was dressed as a Saxon in a tunic and cross-over laces about his legs, and the other was a very elaborate gentleman from a long-ago Court of France.

“Good evening, lovely ladies,” said one of them.

We returned their greeting. One had taken my arm, the other Olivia’s.

“Let’s dance,” said one.

I had the Saxon and Olivia went into a waltz with Richelieu or whoever he was supposed to be.

The Saxon’s arm tightened about me. “What a crowd!”

“What did you expect?” I asked.

“I shouldn’t be surprised if there are some uninvited guests here tonight.”

I felt myself go cold with fear. He knows! I thought. But how? Then I calmed my fears. He was just making conversation.

“It would not be difficult to walk in,” I said.

“Easiest thing possible. I assure you / received my invitation from Lady Massingham.”

“I am sure you did,” I said.

It was difficult to dance, so crowded was the floor. He said: “Let us sit down.”

So we did, at a table in a corner among some green palms.

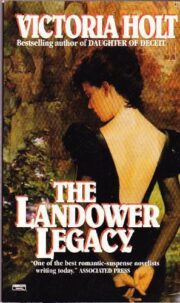

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.