We discussed school and coming out—both with their hazards— and our mother.

Olivia had heard that she was abroad with Captain Carmichael and that he had had to resign his commission in the Army because of the scandal. It seemed strange to me that our mother could leave without wanting to see us—or at least to hear from us. And our father certainly did not want to see me. How different it had been with Cousin Mary!

There was an ache in my heart every time I thought of her.

Then life began to change—not suddenly, but gradually. I went away to school and after the first few weeks enjoyed it. I was extremely good at English literature and had a flair for languages. Miss Bell had taught us a little French and German and I rapidly progressed in those tongues. I played lacrosse with some success; I learned ballroom dancing and to play the piano, and in none of these activities was I a dunce, though I did not exactly excel in any of them.

I began to like school, my new friends, rivalries and all the drama and comedy which seemed to arise out of trivialities. I was not too different from the normal to arouse enmity, yet I had something which was unusual. I think it was a vitality, a tremendous interest in everything that was going on, and a willingness to try everything once. It brought me friends and it made my school life very acceptable.

But I always enjoyed coming home for holidays and in the beginning deluded myself into believing that it would all be changed. My mother would return; my father would be pleased to see me and everything would be happy. Why I should have thought this I could not imagine. It had never been so before.

Olivia was in the throes of “coming out” and after the first few months finding it not so bad as she had thought it might be. She was not an outstanding success in society but she had never expected to be; all she hoped for was to get by, which was just what she was doing. She went to balls and even on occasions to Court—the Court of the Prince and Princess of Wales, that was. The Queen was not given to frivolity and was at Windsor most of the time or hiding herself away in the Isle of Wight. The Prince and Princess of Wales were those who held court and were courted.

But those occasions were rare. The Prince of Wales was what was called a little “fast” and so the society which surrounded him was considered not ideal for young girls on the threshold of their entrance into society.

Between Miss Bell and Aunt Imogen, Olivia was very closely guarded; and she had overcome the dread she had felt at first and was beginning to find life not unpleasant. She still suffered from shyness; and wished that I could accompany her on her engagements. So did I. When there was a ball at the house I was not allowed to go and was resigned to my usual post at the top of the staircase—rather undignified for a girl who was fast becoming an adult.

My father then decided that I should go to a finishing school in France. Once again I was appalled and once again I was soon enjoying it. We lived in a chateau in the mountains, and parties of us would walk into the town once a week and have a cup of coffee and the most delicious pastries, sitting outside a cafe under a brightly coloured sunshade while we talked of what would happen to us when it was our turn to “come out.”

Time was passing. I had forgotten what Captain Carmichael looked like, though when we drank lemonade I remembered vividly sitting at the window on the day of the Jubilee, and how happy we had been then. But I never forgot Paul Landower. I used to sketch his face in one of the sketch-books which we took with us on rambles in the mountains. He grew more and more handsome, more and more noble with the passing of time. Girls would peer over my shoulder and say: “There he is again. I do believe, Caroline Tressidor, that he is your lover.”

They were always talking about lovers. I used to listen and smile and pretend a little … well, perhaps more than a little. It gave one enormous prestige to have had an admirer. I began to hint at a romantic attachment. I invented episodes which had taken place during my stay in Cornwall. Paul Landower had been in love with me but nothing could be done about that because he considered me too young. He was waiting for me to grow up. I almost had now. It became my favourite relaxation—making up little scenes between us, and I told them with such conviction that I began to believe them myself.

I mentioned that he was troubled and this made him even more attractive in their eyes. He was melancholy; he was like Lord Byron, said someone; and I did not deny it. It was no fault of his that his great house had had to be given up. If he had had time he would have retrieved his family’s fortunes.

I told the story of how I had played ghosts with his younger brother. Later, I romanced, I had confessed to Paul. He had taken me into his arms to comfort me. “There!” he said. “It is no fault of yours. You are not to blame.” “And you don’t love me any less for what I did?” I asked. “I love you more than ever … because of it. You did it for me. I love you infinitely.”

Sometimes I came out of my fantasies and laughed at myself. We laughed a lot. Finishing school was fun. Discipline was not the same and as long as we spoke French all the time, that was all that was required of us.

Then it was over. I was seventeen. I would now go home and I supposed my “coming out” would begin. I imagined that I should be drilled by Aunt Imogen as Olivia had been. I thought the dressmakers would be coming to measure me and sew for me as they had for Olivia. But it did not turn out that way.

Once Olivia asked Aunt Imogen when I was going to come out and she reported that Aunt Imogen put her lips together in that way she had and which was like a trap shutting. She had turned away and not answered.

It seemed very strange.

Olivia would have been delighted if we could have gone to the parties together. She had a wardrobe full of beautiful dresses and I longed to have some like them.

“One can only wear them once or twice,” said Olivia. “It’s the same people everywhere and it wouldn’t do for them to think you were so poor you had to go on wearing the same things over and over again.”

“Would it matter?”

“Of course. It’s a sort of parade, isn’t it? Everyone is supposed to be beautiful and rich. It’s all part of one’s assets.”

“Like a cattle market.”

“Yes,” she said thoughtfully, “it is really. Papa is quite well off and nobody seems very eager to take me. I suppose I am not attractive enough even though Papa has enough money to make me worthwhile in the other respect.”

“Oh, Olivia, you sound cynical. I never thought you would be that.”

“I suppose it’s the way life goes. You’ll see when your turn comes.”

But my turn did not come.

Then I noticed a change in Olivia. She seemed to have grown prettier; she was absent-minded; I would find her staring into space, and when I spoke to her she did not always hear me.

“I’ll tell you what,” said Rosie Rundall, with whom, now that we were growing up, we seemed to be on even more friendly terms than before. “Miss Olivia is in love.”

“In love! Olivia! Oh, Olivia, are you?”

“What nonsense,” she said, but she was flushed and confused, so we knew it was true.

“Who is it?” I demanded.

“It’s nothing. It’s no one.”

“But you can’t be in love with no one.”

“Stop teasing,” she pleaded. “What would be the good of my being in love with someone. He wouldn’t be in love with me, would he?”

“Why not?” demanded Rosie.

“Because I’m too quiet and not pretty or clever enough.”

“Believe me,” said Rosie, “and I know what I’m talking about. There’s plenty who like their women that way.”

But however much we tried to probe, Olivia would tell us nothing. I presumed she nurtured a secret passion for someone who was scarcely aware of her existence. But she did not seem to dread going to parties so much—and even on some occasions looked forward to them. I confided in Rosie that it was because she hoped to see this young man, and Rosie thought that very likely.

Rosie herself seemed more lovely, more soignee than ever. She often used to come and show herself to us before going on those nightly jaunts of hers. We used to marvel at her clothes. Olivia, who had learned a great deal since coming out, said that the silk of her dress was of very good quality, and she wondered how Rosie could afford such garments.

Meanwhile I was more or less confined to the schoolroom. I did not have routine lessons but I used to read French with Miss Bell every day. Since my sojourn in France, I spoke that language better than Miss Bell did; candidly she admitted this, but decided it was good for me to “keep it up”—so we conversed and read daily in French.

Olivia came in one day excited because there was to be a ball at Lady Massingham’s. Everyone would be in fancy dress and masked. She liked the idea. “When my face is covered up I don’t feel so shy,” she said. “I think I rather like masked balls.”

“Very exciting not to know to whom you are talking,” I agreed.

“Yes, and they unmask at midnight and you sometimes get a shock.”

“I wish I were going.”

“I can’t think why … Moira Massingham was saying it was very odd that you don’t come out. She says you’re old enough and her mother was saying it was rather strange.”

“I expect it will happen soon,” I said.

“In the meantime you can’t go to the masked ball.”

“Oh, how I wish I could.”

“What as?”

“Cleopatra, I think. I rather fancy myself in the role with an asp curled around my neck.”

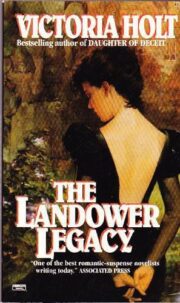

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.