When I asked where she went she gave me a little push and said: “Ah, that’s telling. I’ll tell you when you’re twenty-five.” That was a favourite expression of hers. “One of these days, when you’re twenty-five, you’ll know.”

I was always interested to see the important people who came to the house. In the hall there was a beautiful staircase which wound round and round to the top of the house, with a well in the middle so that from the top floor—where the servants’ sleeping quarters, the nurseries and the schoolroom were situated—one could look right down and see what was happening in the hall. Voices floated upwards and it was often possible to glean all manner of surprising pieces of information in this way. There was nothing so maddening—nor so intriguing—as to have a conversation cut short at some vital point. It was a game I thoroughly enjoyed, although Olivia thought it was somewhat shameful.

“Listeners,” she said, quoting adult philosophy, “never hear any good of themselves.”

“Dear sister,” I retorted, “when do we ever hear anything of ourselves—good or evil?”

“You never know what you might hear.”

“That’s true and that’s what makes it exciting.”

The plain fact was that I enjoyed eavesdropping. There was so much which was kept from us—unfit for our ears, I supposed. I just had an irresistible desire to know these things.

So peering down at the guests as they arrived was a source of great enjoyment. I liked to watch our beautiful mother standing at the top of the stairs at the first floor on which were the drawing room and salon where well-known artistes—pianists, violinists and singers—often came to perform for our guests.

Poor Olivia would squat beside me in torment lest we should be discovered. She was a very nervous girl. I was always the ringleader when it was a question of acting adventurously, although she was two years my senior.

Our governess, Miss Bell, used to say: “Speak up, Olivia. Don’t let Caroline call the tune every time.”

But Olivia was always retiring. She was really quite pretty, but the sort of person people simply did not notice. Everything about her was pleasant but ordinary. Her face was small and pale; I was already taller than she was; her features were small, except her eyes, which were large and brown. “Like a gazelle’s,” I told her, at which she did not know whether to be pleased or hurt. That was characteristic of Olivia. She was never sure. Her eyes were beautiful but she was short-sighted and that gave her a helpless look. Her hair was straight and fine, and no matter how it was restricted, strands would escape, to the despair of Miss Bell. There were times when I felt I had to protect Olivia; but for the most part I was urging her to reckless adventure.

I was quite different in looks as well as in temperament. Miss Bell used to say that she would not have believed two sisters could be so unlike. My hair was darker, almost black; and my eyes were a definite shade of green which I liked to accentuate by wearing a green ribbon in my hair, for I was very vain and aware of my striking colouring. Not that I went so far as to think of myself as pretty. But I was noticeable. My rather snub nose, wide mouth and high forehead—in an age when low ones were fashionable—precluded me from a claim to beauty, but there was something about me—my vitality, I think—which meant that people did not dismiss me with a glance, and they invariably took a second look.

This was the case with Captain Carmichael. To think of him always gave me a thrill of pleasure. He was magnificent in his uniform— the scarlet and the gold—but he always looked very handsome in his riding clothes or dressed for the evening. He was the most elegant and fascinating gentleman I had ever seen and he had one quality which made him irresistible to me: he singled me out for his especial notice. He would smile at me and, if there was an opportunity, would speak to me, treating me as though I were an important young lady instead of a child who had not yet emerged from the schoolroom.

So when I peeped through the stairs I was always looking for Captain Carmichael.

There was a secret I shared with him. My mother was in it, too. It concerned a gold locket, the most beautiful ornament I had ever possessed. We were not allowed to wear jewelry, of course, so it was really very daring of me to wear this locket. True it was under my bodice, which was always tightly buttoned up so that no one could see the locket; but I could feel it against my skin and it always made me happy. It was exciting, too, because it was hidden.

It had been given to me when we were in the country.

Our country house was about twenty miles from London—a rather stately Queen Anne building standing in parklands of some twenty acres. It was very pleasant, but it was not Tressidor Manor, I had heard my father say with some bitterness.

However, most of our days were spent there, our needs provided for by a bevy of servants and Miss Lucy Bell, whom I called the matriarch of the nursery. She seemed old to us, but then everyone over twenty seemed ancient. I think she was about thirty years old when she came to us and at this time she had been with us for four years. She was very eager to fulfil her duties adequately, not only because she needed to earn a living, but, I was sure, because she was in a way fond of us.

In the country we had our nurseries—large pleasant rooms full of light—at the top of the house, giving us delightful views over woodland and green fields. We had our own ponies and rode a good deal. In London we rode in the Row, which was exciting in a way because of the people who bowed to our mother on those occasions when she rode with us; but for the sheer joy of galloping over the springy turf, there was nothing like riding in the country.

It was about a month before we came up to London when our mother arrived unexpectedly in the country. She was accompanied by Everton with hatboxes and general luggage and everything my mother needed to make life agreeable. It was rarely that she came to the country and there was a great deal of bustle throughout the house.

She came to the schoolroom and embraced us both warmly. We were overawed by her beauty, her fragrance, and her elegance in the light grey skirt and the pink blouse with its tucks and frills.

“My dear girls,” she cried. “How wonderful to see you! I wanted to be alone for a while with my girls.”

Olivia blushed with pleasure. I was delighted, too, but perhaps a little sceptical, wondering why she should suddenly be so anxious to be with us when there had been so many opportunities which she had allowed to slip by without any apparent concern.

It was then that the thought occurred to me that she was perhaps less easy to understand than Papa. Papa was omnipotent, omniscient, the most powerful being we knew—under God, and then only just under. Mama was a lady with secrets. At that time I had not been given my locket, so I had no great secret of my own—but I did sense something in Mama’s eyes.

She laughed with us and looked at our drawings and essays.

“Olivia has quite a talent,” said Miss Bell.

“So you have, darling! Oh, I do believe you are going to be a great artist.”

“Hardly that,” said Miss Bell, who was always afraid that too much praise might be harmful.

Olivia was blissful. There was a lovely innocence about her. She always believed in good. I came to think that was a great talent in life.

“Caroline writes quite well.”

My mother was looking blankly at the untidy page presented to her and murmured: “It’s lovely.”

“I did not mean her handwriting,” said Miss Bell. “I mean her construction of sentences and her use of words. She shows imagination and a certain facility in expressing herself.”

“How wonderful!”

The expression in the lovely eyes was vague as she regarded the sheet of paper; but they were alert for something else.

The next day the reason for Mama’s visit to the country arrived. It was one of those important occurrences which I did not recognise as such at the time.

Captain Carmichael called.

We were in the rose garden with Mama at the time. She made a pretty picture with the two girls seated at her feet while she held a book in her hand. She was not reading to us, but it looked as though she might be.

Captain Carmichael was brought out to us.

“Captain Carmichael!” cried my mother. “What a surprise.”

“I was on my way to Salisbury and I thought: Now that’s the Tressidors’ place. Robert would never forgive me if I were in the neighborhood and did not call. So … I thought I would just look in.”

“Alas, Robert is not with us. But it’s a lovely surprise.” My mother rose and clapped her hands together looking like the child who has just been awarded the fairy from the top of the Christmas tree.

“You can stay and have a cup of tea with us,” she went on. “Olivia, go and tell them to bring tea. Caroline, you go with Olivia.”

So we went, leaving them together.

What a pleasant tea-time that was! It was early May, a lovely time of the year. Red and white blossom on the trees and the scent of the newly cut grass in the air, the birds singing and the sun—a nice benign one, not too hot—shining on us. It was wonderful.

Captain Carmichael talked to us. He wanted to hear how we were getting on with our riding. Olivia said little, but I talked a great deal and he seemed to want me to. He kept looking at my mother and their glances seemed to include me, which made me very happy. One thing Olivia and I lacked was affection. Our bodily needs were well catered for, but when one is growing up and getting used to the world, affection, really caring, is what one needs most. That afternoon we seemed to have it.

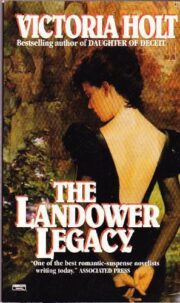

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.