I knew afterwards that I should never have agreed to this mad adventure. But who cannot be wise after the event?

Trying to suppress our laughter we came down the stone staircase. I had to tread cautiously for such medieval staircases were dangerous at the best of times, but with a long skirt which was far too big for me trailing at my feet, I had to watch every step.

Jago, ahead of me, impatiently urged me on, through the corridor to the side door. He drew aside the curtain and we walked in. For a fraction of a second, which seemed at least like ten, we stood there. Jago had miscalculated. Our intended victim was not in the hall as he had planned; she was actually in the gallery. I saw her face freeze into an expression of absolute fear and horror. She screamed. She stepped backwards and caught the rail of the balustrade. It came away in her hands and she fell forward, and down into the hall below.

We stood there for a few seconds staring at her. There was a shout. Mr. Arkwright ran to her. I saw him bending over her. Paul was running towards them.

Jago had turned pale. He drew me back hastily behind the curtain. I could hear Paul shouting orders.

“Come … quickly,” said Jago; and grasping my hand he pulled me out of the gallery.

We stood in the attic, the open trunk before us.

“Do you think she was badly hurt?” I whispered.

Jago shook his head. “No … no … Just a fall … nothing more.”

“It was a long way to fall,” I said.

“They were all there to look after her.”

“Oh, Jago … what if she dies?”

“Of course she won’t die.”

“If she dies … we’ve killed her.”

“No … no. She killed herself. She shouldn’t have been so scared … just at two people dressed up.”

“But she didn’t know we were dressed up. She thought we were ghosts. That’s what we intended.”

“She’ll be all right,” he said. But I was not sure that I thought so.

“We ought to go and see what’s happened.”

“What good would that do? They’re doing all that can be done.”

“But it was our fault.”

He took me by the arm and shook me. “Look! What good can it do? Let’s get out of these clothes. No one will ever know that we wore them. What we’ve got to do now is slip out. We’ll go the way we came. Get that dress off quickly.” He had already stripped off his doublet and was getting into his riding coat.

With trembling fingers I took off the gown. In a few moments we were completely dressed and the trunk was shut. He took my hand and pulled me out of the attic.

We went out the way we had come in and reached the stables without being seen.

We mounted our horses and rode away.

I had said not a word. I was deeply shocked and filled with a terrible remorse.

He said goodbye to me and I rode home to Tressidor. I stayed in my room until dinner time.

I wanted to be alone to think.

The next day I heard the news. Cousin Mary told me.

She said: “There was an accident at Landower. Some people came to see the place and a young woman fell from the gallery into the hall. I told you the place was falling apart. The balustrade in the minstrels’ gallery gave way. Apparently they had been warned about it, but the young woman fell all the same.”

“Is she badly hurt?”

“I don’t know. She’s staying there apparently. The father is there, too. I think they couldn’t move her.”

“She must be badly hurt then.”

“I should think that would put them off buying the place.”

“Did they say why she fell?”

“I didn’t hear. I take it she leaned against the woodwork and it gave way.”

I went about in a dream that day. I had forgotten even that my departure was imminent. I did not see Jago. I wondered whether he avoided me as I did him.

Once more I had the news from Cousin Mary.

“I don’t think she’s all that badly hurt but they’re not sure yet. Poor girl. She says she saw ghosts in the gallery. The father pooh-poohs the idea. They’re very practical, these Yorkshire types. The Landowers are making a great fuss of them … looking after them, showing them a bit of that gracious hospitality which they’ve come to find. At least that’s what I’ve heard.”

“I don’t suppose they’ll want the place now.”

“I’ve heard to the contrary. They’re growing more and more fond of it … so one of the servants told our Mabel. I gather that the man has convinced his daughter that it was the shadows which made her fancy she saw the ghost.”

The time was passing. One more day and Miss Bell was due.

I went round to say goodbye to the people I had known. I lingered at the lodge and had tea with Jamie McGill. He shook his head very sadly and said the bees had told him that I would be back one day.

I did see Jago before I left. He looked sad and was a different person to me now. We were not young and carefree any more.

Neither of us could forget what we had done.

I said: “We ought not to have run away afterwards. We ought to have gone down to see what we could do.”

“There wasn’t anything we could have done. We would have only made it worse.”

“At least she would have known that she had not seen any ghosts.”

“She’s half convinced that she imagined she did. Her father keeps telling her so.”

“But she saw us.”

“He says it was a trick of the light.”

“And she believes him?”

“She half does. She seems to have a high opinion of Pa. He’s always been right. You want to confess, don’t you, Caroline? I believe you’ve got a very active conscience. That’s a terrible thing to go through life with. Get rid of it, Caroline.”

“Is she very bad?”

“She can’t walk yet, but she’s by no means dying.”

“Oh, I wish we hadn’t done it.”

“So do I. Moreover, it’s had the opposite effect from what I planned. They’re staying in the house. Paul’s treating them like honoured guests … and so is my father. They’re liking the place more. They’ve decided to buy it, Caroline.”

“It’s a judgement,” I said.

He nodded mournfully.

“Oh, I do hope she is not going to be an invalid for life.”

“Not Gwennie. Pa wouldn’t allow it. They’re tough, these Arkwrights, I can tell you. They didn’t get all that brass by being soft.”

“And I shall be leaving tomorrow.”

He looked at me mournfully.

So all our schemes had come to nothing. Landower was to be sold to the Arkwrights and I was going home.

The next day Miss Bell arrived, and the day after that we left for London.

THE MASKED BALL

Three years had passed since my return from Cornwall and my seventeenth birthday was approaching.

For the first six months I thought often of Cousin Mary at Tressidor Manor, James McGill at the Lodge and Paul and Jago at Landower Hall. I particularly thought of Paul. I experienced a feeling of nostalgic longing every morning when I awoke. I told and retold my adventures to Olivia, who was avid to hear of them and listened entranced. Maybe I embellished them a little. Perhaps Landower Hall sounded like the tower of London and Tressidor Manor a little like Hampton Court. I talked of Paul Landower more than anyone else. He had become a handsome hero endowed with every noble quality. He was something between Alexander the Great and Lancelot; he was Hercules and Apollo; he was noble and invincible. Olivia’s lovely shortsighted eyes glowed with sentiment when I talked of him. I invented conversations with him. Olivia envied me my adventures; she was horrified at the outcome of the ghostly episode, and it never occurred to her to wonder why the omnipotent Paul had failed to save his own home. Cousin Mary had written only once. She was not a letter writer, I soon discovered, though I was sure that if I went back to the Manor we should take up our relationship where it had left off. In that one letter she did tell me that Landower Hall had been sold to the Arkwrights and that Miss Arkwright could not have been really badly hurt because she was now walking about. The Arkwrights were established in the Hall and the Landowers had moved to a farm on the edge of their estate. Apart from that everything was much the same as usual.

I wrote back and that letter remained unanswered. I did not write to Jago but I was sure that the old farmhouse, which was now the home of the Landowers, would be a very melancholy household indeed.

My father expressed no pleasure at my return. In fact I did not see him until I had been back three days; and then he scarcely looked at me.

Resentment flamed into my heart and I felt wretchedly hurt and longed for the casual affection of Cousin Mary.

Miss Bell was her old self. She behaved as though I had never been away; but my great consolation was Olivia, who implied a hundred times a day how pleased she was to have me back.

She had her own problems and the greatest of these was her “coming out.” She was extremely nervous and was being groomed by Aunt Imogen—an ordeal if ever there was one—and there were so many do’s and don’ts that she was becoming quite bewildered.

I had not been home more than three weeks when I heard I was to go away to school at the beginning of the September term. This was a blow no less to Olivia and Miss Bell than it was to me.

Olivia had not gone away to school. I could only believe that my father still remembered that if it had not been for me he might have gone on in blissful ignorance of my mother’s love affair with Captain Carmichael, and for this reason could not bear the sight of me.

Olivia was going to miss me. Miss Bell was anxious about the post of governess; but she was reassured almost immediately. She was to stay on and look after Olivia and presumably me during holidays from school when—I imagined most reluctantly—my father would have to allow me to return to the family home.

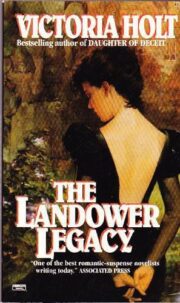

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.