“It’s been nice talking to you,” said Mr. Arkwright. “Come from these parts, do you?”

“Not far away.”

“Do you know the place well?”

“I know it.”

“Lot of rot about ghosts and things.”

Jago put his head on one side and shrugged his shoulders. “Best of luck,” he said. “Good day to you.”

We came out into the open and made our way to the smithy.

“Can you imagine them at Landower?” I asked.

“I refuse to think of it.”

“I believe you frightened Miss Gwennie.”

“I hope so.”

“Do you think it will do any good?”

“I don’t know. He’s only got to see the place to want it. He’s got what he calls the ‘brass,’ and he’s got his lawyer and he’ll drive a hard bargain, I don’t doubt.”

“I pin my hopes on Gwennie. You really scared her with the ghosts.”

“I rather thought I did.”

We started to laugh and ran the rest of the way to the smithy.

I had agreed to meet Jago that afternoon. He looked excited and I guessed that he had one of his wild plans in his mind and that he wanted to talk to me about it. I was right.

“Come to the house,” he said. “I’ve got an idea.”

“What?” I asked.

“I’ll explain. First come along.”

We put our horses in the Landower stables and went into the house. He took me in by way of a side door and we were in a labyrinth of corridors. We mounted a stone spiral staircase with a rope banister.

“Where are we?” I asked.

“This part of the house isn’t used much. It leads directly to the attics.”

“You mean the servants’ quarters?”

“No. The attics which are used for storage. I had an idea that there might be something of value tucked away there … something which would save the family fortunes. Some Old Master. Some priceless piece of jewellery … something hidden away at some time, perhaps during the Civil War.”

“You were on the side of the Parliament,” I reminded him, “and saved everything by changing sides.”

“Not till they were victorious.”

“There is no virtue in that, so don’t sound so smug.”

“No virtue … only wisdom.”

“I believe you’re a cynic.”

“One has to be in this hard world. However, we saved Landower, whatever we did. I’d do a lot to save Landower, and that’s been the general feeling in the family throughout the ages. Never mind that now. I’ll show you what I’m driving at.”

“Do you mean you’ve really found something?”

“I haven’t found that masterpiece … that priceless gem or work of art or anything like that. But God works in a mysterious way and I think He has provided the answer to my prayers.”

“How exciting. But you are as mysterious as God. You are the most maddening creature I know.”

“God,” he went on piously, “helps those who help themselves. So come on.”

The attic was long, with a roof almost touching the floor at one end. There was a small window at the other which let in a little light.

“It’s eerie up here,” I said.

“I know. Makes you think of ghosts. Dear ghosts, I think they are coming to our aid. The ancestors of the past are rising up in their wrath at the thought of Landower passing out of the family’s hands.”

“Well, I’m waiting to see this discovery.”

“Come over here.” He opened a trunk. I gasped. It was full of clothes.

“There!” He thrust his hands in and brought out a pelisse of green velvet edged with fur.

I seized it. “It’s lovely,” I said.

“Wait,” he went on. “You’ve seen nothing yet. What about this?” He brought out a dress with large slashed sleeves. It was made of green velvet and very faded in some places, but I was sure the lace on the collar had once been very fine. There was an overskirt which opened in the front to reveal a petticoat-type skirt beneath. This was of brocade with delicately etched embroidery. Some of the stitching had worn away and there was a faintly musty smell about the garment. It was not unlike a dress one of the Tressidor ancestresses was wearing in her portrait in the long gallery at the Manor, so I judged it to be the mid-seventeenth century. It was amazing to contemplate that the dress had been in the trunk all that time.

“Look at this!” cried Jago. He had slipped off his coat and put on a doublet. It was rather tightly fitting, laced and braided, of mulberry velvet, and must have been very splendid in its day. Some of the braid was hanging off and it was badly faded in several places. He took out a cloak which he slung over one shoulder. It was of red plush.

“What do you think?” he asked.

I burst out laughing. “You would never be mistaken for Sir Walter Raleigh, I fear. I do believe that if we were out of doors in the mud you would spread your cloak for me to walk on.”

He took my hand and kissed it. “My cloak would be at your service, dear lady.” I laughed, and he went on: “Look at these hose and shoes to go with it. I should be a real Elizabethan dandy in these. There’s even a little hat with a feather.”

“Magnificent!” I cried.

“Well, you in that dress and me in my doublet and hose … what impression do you think we’d make?”

“They’re different periods for one thing.”

“What does that matter? They’d never know. I thought that in the shadows … in the minstrels’ gallery, we’d make a good pair of ghosts.”

I stared at him, understanding dawning. Of course, the Arkwrights were coming to view the house this afternoon.

“Jago,” I said, “what wild scheme have you in mind just now?”

“I’m going to stop those people buying our house.”

“You mean you’re going to frighten them?”

“The ghosts are,” he said. “You and I will make a jolly good pair of ghosts. I’ve got it all planned. They’re in the hall. You and I stand in the shadows in the minstrels’ gallery. We’ll appear and then … disappear. But not before Gwennie Arkwright has seen us. She’ll be so scared that Mr. A. for all his brass will have to give way to entreaties.”

I laughed. It was typical of him.

“Full marks for imagination,” I said.

“I’ll have them for strategy as well. How could it fail? I want your help.”

“I don’t like it. I think that girl would be really scared.”

“Of course she will be. That’s the object of the exercise. She’ll insist that Pa does not buy the place and they’ll go off somewhere else.”

“It only postpones the evil day. Or do you propose that when the next prospective buyer comes along we perform our little ghostly charade again? You forget. I shan’t be here to help you.”

“By that time I’m going to find something of real value in the attics. All I want is time. I’m also working on some way of keeping you here.”

“I’m afraid you’d never frighten Miss Bell away with ghosts.”

“My dear Caroline, I have so many ideas going round and round in my head. I shall think of something. There is still time. What we have to concentrate on now is the Arkwrights. You are going to help me, aren’t you?”

“Wouldn’t one ghost do?”

“Two’s better. Male and female. Come on. Don’t be a spoil-sport, Caroline. Put on the dress. Just see how you look.”

I couldn’t help falling in with the plan. The dress was too big for me but it did look effective. There was an old mirror in the attic. It was mottled and gave back a shadowy vision. Reflected in it we certainly did look like two ghosts from the past.

We rolled about, laughing at each other. I was sober suddenly, wondering how we could give way to such merriment with disaster hanging over both our heads. He was about to lose his beloved home and I was soon to leave a life which had become interesting and exciting to go back to one of dreary confined routine. Yet there could be these moments of sheer enjoyment. I was grateful to him for making me forget even for such a short while.

I said: “I’ll help.”

“All we have to do is stand there. We want to catch Gwennie on her own if we can. Perhaps while Pa is examining the panelling and calculating how much brass will be required to put it in order. There is a movement from the gallery. Gwennie looks up and sees standing there, glaring down at her, two figures from the past. Perhaps we shake our heads at her dismally … warningly … menacingly … but clearly indicating that she should not bring her father to Landower.”

“You make the wildest schemes.”

“What’s wild about this? It’s sheer logic.”

“Like keeping me in the dungeons with rats for company?”

“That was a figure of speech. I hadn’t worked that out properly. This is all carefully thought out.”

“When do they arrive?”

“Any time now. Paul will show them round … or my father will. We’ll choose our moment. We must be prepared.”

“What about my hair?”

“How did they wear it in those days?”

“Frizzy fringes, as far as I know.”

“Just tie it right back. But perhaps if you have it piled up …”

“I’ve no pins. I wonder if there is anything in the trunk. A comb or something.”

We looked. There were no combs but there were some ribbons. I tied my hair with a bow of ribbon, so that it stuck out like a tail at the top of my head. The ribbon didn’t match the dress but it was quite effective.

“Splendid!” cried Jago. “Now we’ll take up our places in the gallery so that we are all ready for the great moment.”

I giggled at myself wearing the elaborate dress with my riding boots protruding incongruously from the skirt.

“They won’t see your feet,” said Jago consolingly. “Now we reach the gallery by way of a side door. It’s the door through which the musicians enter. It’s concealed by a curtain. When we leave we can cut through a corridor to the stone staircase and up to the attics. Couldn’t be better.”

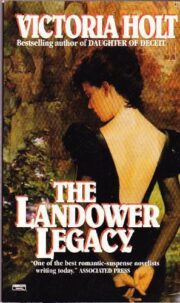

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.