We were taken into a sitting room and almost immediately hot soup was brought in.

I think Miss Bell would have preferred to wash first, but she knew that one in her position did not go against the wishes of people in authority and there was no doubt that Cousin Mary was accustomed to command.

The room was cosy and panelled, but I was too uncertain and tired to notice very much and in any case I should have plenty of time to discover my surroundings. The soup was served immediately and we did need it. There was cold ham to follow and apple pie with clotted cream—and cider to drink.

Cousin Mary had left us while we were eating.

I whispered to Miss Bell: “I do wish you could have stayed for a day or so.”

“Never mind. Perhaps it is better thus.”

“Just think. You’ll have that long journey again tomorrow.”

“Well, I shall have the satisfaction of knowing that you are here.”

“I am not sure that I am going to like it. Cousin Mary is rather … rather …”

“Hush. You don’t know what she is like yet. She seems to me very … worthy. I am sure she is a lady of great integrity.”

“She is like my father.”

“Well, they are first cousins. There is often a family resemblance. It is better than being among complete strangers.”

“I wonder what Olivia is doing.”

“Wondering what you are doing, I imagine.”

“I wish she were here.”

“I daresay she wishes she were.”

“Oh, Miss Bell, why did I have to go away so suddenly?”

“Family decisions, my dear.”

Her lips were clamped together. She knew something which she was not going to tell me.

I was surprised that I could eat so heartily, and as we were finishing the meal Cousin Mary came back.

“Ah,” she said. “That’s better, eh? Now, if you’re ready I’ll take you to your rooms. You’ll have to be up early in the morning, Miss Bell. Joe will take you to the station. You should get a good night’s sleep. We’ll give you a packed lunch and return you to my cousin in the good order you left. Come with me now.”

We mounted the staircase. The long gallery was on the first floor. As we passed through it, long dead and gone Tressidors looked down on me. The fast fading light gave it an eerie look.

There was a staircase at the end of the gallery and this we mounted. We were in a corridor in which there were many doors. Cousin Mary opened one of them.

“This is yours, Caroline, and Miss Bell’s is next to it.” She patted the bed. “Yes, they’ve aired it. Oh, there’s your trunk. I shouldn’t unpack it until tomorrow. One of the maids can help you then. There’s hot water. You can wash off the train smell. Always think you carry that with you for a while. And then I should think a good night’s sleep—and in the morning you can start to explore … get to know the house and our ways. Miss Bell, if you’d step along with me...

At last I was alone. My bedroom was high-ceilinged, the walls panelled; a little light filtered through the thick glass of the windows. I noticed the candles in their carved wooden sticks over the fireplace. My trunk had been placed in one corner; my hand-case was on a chair. I had a nightgown and slippers in it so I could well leave unpacking until the morning. The floor sloped a little and mats covered the boards; the curtains were heavy grey velvet; and there was a court cupboard which looked solid and ancient, and an oak chest on which stood a Chinese bowl. On a dressing table with numerous drawers was a sling-back mirror. I took a look at myself. I was paler than usual and my eyes looked enormous. There was no mistaking the apprehension in them. Who would not be apprehensive in such circumstances?

The door opened and Cousin Mary came in.

“Goodnight,” she said brusquely. “Go to bed. We’ll talk tomorrow.”

“Goodnight, Cousin Mary.”

She gave just a nod of the head. She was not unwelcoming, but she was not warm either. I was not sure yet of Cousin Mary. I sat down on the bed and resisted the impulse to cry weakly. I was longing for my familiar room, with Olivia seated at the dressing table plaiting her hair.

There was a knock on the door and Miss Bell came in.

“Well,” she said. “Here we are.”

“Is it how you thought it would be, Miss Bell?”

“Life is rarely what one thinks it will be—so therefore I make no pre-judgments.”

I felt myself smiling in spite of everything.

Oh, how I was going to miss my precise Miss Bell!

She sensed my emotion and went on: “We are both exhausted, you know. Much more tired than we realize. What we need to do is rest. Goodnight, my dear.” She came to me and kissed me. She had never done that before and it aroused a sudden emotion in me. I put my arms round her and hugged her.

“You’ll be all right,” she said, patting me brusquely, ashamed now of her own emotion. “You’ll always be all right, Caroline!”

Comforting words!

“Goodnight, my child.”

Then she was gone.

I lay in bed. Sleep eluded me at first. Pictures crowded into my mind, shutting out my tiredness. The men on the train, the great fortress which was their home, Joe driving the trap, the man with the bees … and finally Cousin Mary who was like my father and yet … quite different.

In time I should know more of them. But now … I was very tired and even my apprehension could not keep sleep at bay.

I was awakened by Miss Bell sitting on my bed, ready for her journey.

“Are you going … already?”

“It’s time,” she said. “You were in a deep sleep. I wondered whether to wake you, but I thought you would not want me to go without saying goodbye.”

“Oh, Miss Bell, you’re going. When shall I see you again?”

“Very soon. It’s just a holiday, you know. I shall be there when you come back.”

“I don’t think it is going to be quite like that.”

“You’ll see. I’ll have to go. The trap is down there. I must not miss that train. Good luck, Caroline. You’re going to have an interesting time here and you won’t want to come back to us.”

“Oh, I shall. I shall.”

“Goodbye, my dear.”

For the second time she kissed me, and then she hurried from the room.

I lay wondering, as I had so many times before, what life was going to be like.

There was a knock on my door and Betty, the maid I had seen on the previous evening, came in with hot water.

“Miss Tressidor said not to disturb you if you be sleeping, but the lady what brought you be gone and I reckoned her’d come and say goodbye, wouldn’t her?”

“She did, and I am awake and glad to have the hot water.”

“I’ll take away last night’s,” she said. “And Miss Tressidor says that if you’re up you can have breakfast with her at half-past eight.”

“What’s the time now?”

“Eight o’clock, Miss.”

“I’ll be ready then. Where will she be?”

“I’m to be here to take you down to her. You can get lost in this house till you know it.”

“I’m sure you can.”

“Anything you want, Miss. Just ring the bell.”

“Thank you.”

She went on. My homesickness was being replaced by a desire for discovery.

Precisely at eight-thirty Betty appeared.

“This be the bedrooms up here, Miss,” she told me, “and there’s another floor above, too. We’ve got plenty of bedrooms. Then above them is the attics … servants’ quarters as they say. Then there’s the long gallery and the solarium … then there’s the rooms on the ground floor.”

“I can see I have a lot to learn if I am to find my way about.”

We came down the staircase.

“This be the dining room.” She paused, then she knocked.

“Miss Caroline, Miss Tressidor.”

Cousin Mary was seated at the table. Before her was a plate of bacon, eggs and devilled kidneys. “Oh, there you are,” she said. “The governess left half an hour or more ago. Did you have a good night? Yes, I see you did, and now you’re ready to take stock of your surroundings, eh? Of course you are. You’ll want to eat a good breakfast. Best meal of the day, I always say. Stock yourself up. Help yourself.”

She showed a certain amount of concern for my well-being, which was comforting, but her habit of asking a question and answering it herself made for a certain one-sided conversation.

I went to the sideboard and helped myself from the chafing dishes.

Cousin Mary took her eyes from the plate and I felt them on me.

“Feel a bit strange at first,” she said. “Bound to. You should have come before. I should have liked to have visits from you and your sister … and your father and mother … if he’d been different. Families ought to keep together, but sometimes they’re better apart. It was my inheriting this place they didn’t like. There was no doubt about that. I was the rightful heir, but a woman, they said. There’s a prejudice against our sex, Caroline. I don’t suppose you’ve noticed it much yet.”

“Oh yes, I have.”

“Your father thought he should step over me and take this place because I was a woman. Only over my dead body, I said; and that’s what it amounts to. If I died, I suppose he’d be the next. That’s a consummation devoutly to be wished—for him, I don’t doubt. But I feel very differently about the matter, as you can imagine.” She gave a little laugh which was rather like a dog’s bark.

I laughed with her and she looked at me with some approval.

“Cousin Robert is a very able man but he still lacks the power to get rid of his Cousin Mary.” Again that bark. “Well, we’ve done without each other all these years. You can imagine how taken aback I was when I got the letter from Cousin Imogen telling me that they’d be glad if I invited you for a month or so.”

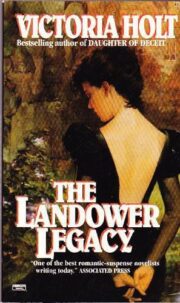

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.