“Closer to nine, I think,” Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore said. “We met for the first two months in Gwen’s parlor. But it soon became obvious that would not do.”

“For the purposes of?”

“Why, acquainting women with the benefits of travel, of course.” Aunt Guinevere beamed. “And providing expert assistance and guidance through lectures and brochures and touring services to fulfill their dreams of adventure through travel.”

“And for this expert assistance—” He glanced down at the paper in front of him. “You charge your membership a full one pound sterling every month.” He looked up at the ladies. “Is that correct?”

“It’s really quite reasonable,” Aunt Guinevere chided.

“And if you pay for an entire year at once, we give you a discount. A mere ten pounds.” Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore smiled. “We are a bargain.”

Mrs. Higginbotham nodded. “There is a great deal to take into account when one is traveling beyond England’s shores, you know, Mr. Saunders.”

“Yes, I can imagine,” he said. “And for these alleged benefits—”

“I would dispute the word alleged,” Mrs. Higginbotham said under her breath.

“You now have—” Derek sifted through the papers “—some ninety members. Is that right?”

“Actually, we’re approaching one hundred.” Pride curved Aunt Guinevere’s lips. “We had no idea we’d grow so quickly.”

“You can see why we could no longer meet in Gwen’s parlor.” Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore leaned forward in a confidential manner. “You’d be surprised at how many women are longing to throw off the shackles of everyday existence and live an adventurous life of travel. It’s quite remarkable.”

“No doubt.” Derek’s gaze shifted from one lady to the next. “So, the society brings in nearly one hundred pounds a month. And for their dues your members receive?”

The ladies exchanged resigned glances.

“Our expert advice on traveling the world,” Aunt Guinevere said in a well-rehearsed manner.

“The companionship and camaraderie of like-minded women,” Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore added.

“As well as knowledgeable guidance and, for a minor additional fee, the providing of arranged travel services,” Mrs. Higginbotham finished with a flourish.

“And that, dear ladies, is where we have a problem.” Derek folded his hands together on the stack of papers and studied the women. All three had adopted blameless expressions, and all three had nearly identical glints of cunning in their eyes. “I shall grant you that the society does indeed provide a convivial atmosphere for ladies with similar interests in travel.”

“That was mine.” Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore smirked.

“However.” Derek’s tone hardened.

Mrs. Higginbotham sighed. “I do so hate it when men use the word however in that forbidding tone. Nothing good ever came of a man starting a sentence with however.”

Derek’s jaw tightened. “Nonetheless—”

“Nonetheless is just as bad.” Mrs. Higginbotham huffed.

He ignored her. “According to your membership brochure—”

“Isn’t it lovely?” Aunt Guinevere said. “Poppy designed it herself. Don’t you think it’s fetching with her drawing of the pyramids in Egypt and the Colosseum in Rome and those charming American natives? Poppy is quite an accomplished artist.”

“Goodness, I wouldn’t say I was accomplished. I am scarcely more than an amateur.” Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore blushed and waved off the comment in a modest manner. “I had hoped to be an artist when I was young, but that was one of those silly, girlish dreams and best forgotten.”

“Nevertheless,” Mrs. Higginbotham said staunchly. “You’re very good.”

“The brochure is indeed extremely well done.” Derek struggled to keep the impatience from his voice. “However—”

Mrs. Higginbotham grimaced.

“Aunt Guinevere, it’s my understanding that you rarely, if ever, traveled with Uncle Charles, which would seem to negate the claim of expert in regard to your knowledge of travel.”

“I suppose...” Aunt Guinevere hedged. “If one goes strictly by personal travel...”

“I suspect as well—” his gaze shifted between his great-aunt’s coconspirators “—neither Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore or Mrs. Higginbotham have substantially more travel experience than you do.”

“On the contrary, Mr. Saunders.” Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore sniffed. “I resided for nearly six weeks in Paris as a girl.”

“And the late Colonel Higginbotham and myself spent several summers in the Lake District.” Mrs. Higginbotham paused. “Admittedly, that does not equate to foreign travel but it is some distance from here.”

“Domestic travel as it were,” Aunt Guinevere said helpfully.

“And yet I imagine when your members speak of their dreams of adventure through travel, Lake Windermere is not the first destination that comes to mind.”

“Lovely spot, though,” Mrs. Higginbotham murmured.

“There is no need to raise your voice, dear.” Aunt Guinevere cast him a disapproving frown.

“I did not raise my voice. In fact, I have been doing my very best not to raise my voice.” He drew a steadying breath. “Correct me if I’m in error, ladies, but by no stretch of the most fertile imagination could any of you be considered experts in travel or the arrangement of travel.”

Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore heaved a long-suffering sigh. “I suppose if one wanted to base judgment on actual experience alone, that might be considered inaccurate.”

“Nonsense,” Mrs. Higginbotham said. “I lived with the colonel for thirty-seven years, and he traveled continuously to the most interesting and exotic places. I would think the years spent in his company listening to his endless tales would negate the minor detail that I did not actually accompany him.”

Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore nodded. “Nor did I accompany my dear Malcolm, but he did keep me apprised of his adventures and very often asked my opinion when he was planning one expedition or another.”

“As did your uncle Charles,” Aunt Guinevere added. “Why, he frequently said he could not step a foot off English shores without the benefit of my advice.”

Derek stared in stunned disbelief.

“So you see...” Aunt Guinevere smiled pleasantly, but triumph glittered in her eyes. “Even though we have not traveled extensively, we do have extensive travel knowledge.”

All three ladies shared equally smug looks.

“Let me put it this way.” Derek struggled to keep his voice level. “While it could possibly be argued that you have a certain level of expertise as it relates to travel, most rational individuals would think your claim ridiculous. As would a magistrate or any court of law. What you are engaged in here, ladies, is fraud.”

“Don’t be absurd, Derek.” Aunt Guinevere scoffed.

“I’m not being absurd, I only wish I were. At the very least, the consequences of your activities are scandal. At the worst—prison.” He fixed them with a firm look. “You are falsely representing yourselves as being able to supply a service you are not qualified to provide. And for that you are taking money from women who trust you.”

“Well, we had to do something,” Mrs. Higginbotham snapped. “Minimal pensions and minor inheritances are simply not enough to survive on even with the most frugal manner of living.”

Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore nodded. “It’s not easy getting on in years. It would be one thing if our dear husbands were still with us, but as they are not, we have each found ourselves tottering precipitously on the very edge of financial despair.”

“To be blunt, Derek,” Aunt Guinevere said coolly, “we have outlived our financial resources. We were very nearly penniless.”

“But you all have families,” he said before he thought better of it. He tried to ignore a fresh wave of guilt. He’d had no idea of his great-aunt’s circumstances, and he doubted his mother did, either. Aunt Guinevere had not seen fit to inform them, although, admittedly, they had not taken it upon themselves to inquire after her, either.

“Distant and disinterested.” Mrs. Higginbotham sniffed.

“None of us were fortunate enough to have had children.” Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore shrugged. “Nothing can be done about that now, although I suppose, in hindsight, breeding like rabbits would have provided some sort of insurance against being left alone in dismal financial circumstances. Still, I daresay poor Eleanor Dorsey has not found it so and she had nine children.”

The other ladies murmured in agreement.

“Even so,” Derek began.

“We have all lived relatively independent lives, Derek.” Aunt Guinevere raised her chin a notch and met his gaze firmly. “We took care of ourselves and each other when our husbands were off doing all those things men so enjoy and do not for a moment think women would appreciate, as well. We do not, at this point in our lives, relish the thought of throwing ourselves on the mercy of relations who barely acknowledge our existence. Nor do we intend to.”

Mrs. Fitzhew-Wellmore squared her shoulders. “I will not be relegated to the category of poor relation.”

“And if it came to that, we would much prefer, all three of us...” Mrs. Higginbotham’s eyes blazed with determination. “Prison.”

“I doubt that,” he said sharply, then drew a deep breath. “Forgive me, ladies. I do see your position. Truly I do, and I promise you I shall do everything I can to help alleviate your financial woes, but you must understand you cannot continue this endeavor.”

“I don’t see why not.” Mrs. Higginbotham crossed her arms over her chest. “Our members flock to our meetings and lectures and are quite content with our services. Thus far, we have not had one resign her membership. Why, we’ve had no complaints whatsoever from our members.”

“Not from members perhaps.” He leaned forward in his chair. “But do you recall a Miss India Prendergast?”

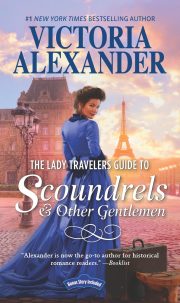

"The Lady Travelers Guide to Scoundrels and Other Gentlemen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Lady Travelers Guide to Scoundrels and Other Gentlemen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Lady Travelers Guide to Scoundrels and Other Gentlemen" друзьям в соцсетях.