“It’s none of your concern.” Her glass was empty, and he refilled it, surprised that she did not protest. “But it’s not a secret. My employer asked me to telegraph him regularly and inform him of our progress.” She raised her glass to him. “He doesn’t trust you, either.”

He gasped in feigned dismay. “And what, pray tell, have I done to earn his distrust?”

“Good Lord, Derek, you have quite a reputation.”

“Yes, you mentioned that in London.”

“It bears repeating. You can’t be so dim as to not be aware of your tarnished image.”

“I am well aware of it. However, I am in the process of reform.”

She stared at him for a long moment, then snorted in disbelief. “Come now. Men like you do not reform.”

“Men like me?”

“Your misdeeds are public knowledge. Your name can scarcely come up in conversation without someone relating one unfortunate incident or another.” She set down her glass and ticked the points off on her fingers. “One of your best known indiscretions involved Lady Philbury—”

“Who was estranged from her husband,” he said casually.

“But married nonetheless. There was an incident centered on an indecent painting—”

“A youthful error in judgment on my part.” He waved off her comment. “Surely such transgressions can be forgiven?”

“But never forgotten. There was a questionable sporting event in Hyde Park. A race I believe.”

“Scarcely worth mentioning.” He snorted in dismissal. “And might I point out neither animal nor human suffered the tiniest injury. Other than perhaps to their dignity.”

“There was a wager involving the auction of undergarments of a royal personage.”

He winced. “Yes, well, that was perhaps not one of my finer moments. Although it really wasn’t my idea.”

“Giving credit to someone else does not absolve you of responsibility,” she said primly. “There was a masked ball where the ladies in question—”

“That’s quite enough, but thank you for allowing me to relive my wicked ways.” He grinned. In hindsight, there were a great many things he’d done, and nearly as many that he’d failed to do, that now struck him as foolish and asinine. But nearly all of them had been fun at the time.

“Ways you say are in the past.”

“The very definition of reform.”

“That remains to be seen.”

“One does have to grow up at some point, you know.” He smiled wryly. “Whether one wants to or not.”

“One can only hope. But you can see why your past behavior does not engender complete trust in someone like Sir Martin.”

“I gather he is most trustworthy.”

“Well, he’s not prone to silly pranks and disgraceful behavior, so in that respect, yes. He is also honorable, respectable and quite brilliant.”

“He sounds perfect.”

“Good Lord, no.” She scoffed. “He is disorganized, prone to distraction and rarely sees anything through to completion.”

“I see. Quite a handful then for Lady Luckthorne,” he said even though he already knew there was no Lady Luckthorne.

“Oh, there is no Lady Luckthorne.”

“Then who manages his household, his staff, his social engagements? That sort of thing.”

“I do, of course.”

“I thought you were a secretarial assistant?”

“I fear the term is rather broad when it comes to Sir Martin.” She sipped her wine. “I do very nearly everything he needs so that he needn’t waste his valuable time and can spend it in more beneficial pursuits. Mostly of an intellectual or academic or scientific nature. Experiments and inventions and the like. As well as research, writing, collecting—that sort of thing.”

“And this honorable, respectable, brilliant gentleman sees nothing the least bit improper about an unmarried man working in close proximity with an unmarried woman in his own home.”

“Not at all.” She waved off the charge. “As there is nothing nor has there ever been anything untoward between us. Not that I would permit such a thing.”

“No doubt,” he said under his breath.

Her eyes narrowed. “What do you mean by that?”

“Scandal, my dear India, is as often as not in the eyes of the beholder. As aboveboard and innocent as it might be, some people might view your employment with Sir Martin to be more of an arrangement than a legitimate position.” He braced himself.

She stared at him for a long moment, then snorted back what might have been a laugh. “Then some people have never met either Sir Martin or myself.”

“Yes, well, trust me when I say it’s not necessary to know someone personally to spread tales about their misdeeds. I am a prime example of that.”

“In your case, there are witnesses to your misadventures.” She smiled in a smug manner. “Dozens I would say, perhaps hundreds.”

“And there are no witnesses as to what transpires between an odd sort of chap and his lovely assistant behind closed doors.”

“Do not attempt to charm me, Derek, with words like lovely. It will not work. And furthermore nothing goes on behind closed doors with Sir Martin. I do feel a certain...sisterly affection for him. In the manner I imagine I would an older brother. And I’m certain any feelings that he might have for me are very much the same.” She paused to finish her wine. “Goodness, I’ve worked for the man for eight years. I would think he would have said something by now if he felt otherwise.”

“And if he did?”

“I would leave his employment at once.” She held out her glass to be refilled yet again. “I will not allow myself to be put in an awkward position.”

“And yet you insisted on traveling with me.”

“That’s entirely different. We—” she aimed a pointed finger at him “—are traveling in pursuit of a higher purpose. A noble calling, if you will. We are off to rescue Heloise.”

“Whether she wants rescuing or not.”

“And we have chaperones,” she added. “Nothing here for witnesses to spread gossip about.”

“Come now, India, I would have thought you far smarter than that.” He met her gaze directly. “Surely you realize, whether it’s true or not, the most interesting, most tantalizing, juiciest gossip is about that behavior that has no witnesses at all.”

“Regardless, that doesn’t mean one can do whatever one wants. There are rules, Derek. And rules are meant to be followed.”

“Always?”

“Yes,” she said firmly, then paused. “Although I suppose there might be extreme circumstances under which it might be acceptable to bend or even break a rule. I can’t think of an example offhand, but I am willing to acknowledge the possibility.”

“How very broad-minded of you,” he said with a grin and raised his glass to her. “Here’s to finding an example.”

CHAPTER ELEVEN

One should keep in mind where one is bound when selecting attire for a journey. A wardrobe for the Egyptian desert would not be appropriate in the Bavarian Alps. However, one can never go far afield with a good-quality skirt and sturdy walking boots. The knowledgeable lady traveler always checks her luggage more than once to make certain it is properly labeled. Lost luggage will disrupt the trip of even the most steadfast among us.

—The Lady Travelers Society Guide

EVEN AT THE house she shared with Heloise in London, India dressed for dinner. It was proper and expected. But her gray suit was simply not up to the task of dining yet again in Lord Brookings’s ornate Parisian dining room with its mural-painted walls and sparkling gold-and-crystal chandelier. Still, she made do—she had no choice. It would have been rude to have stayed in her room. Nonetheless, being impolite might well have been better than being present at dinner. She wouldn’t have believed it possible but she felt even more out of place at the table with his lordship, Derek and the Greers than she had in the lobby of the first Grand Hotel although the second, third and all the way through today’s seventh, while not quite as grand, were still impressive.

It was early evening when Derek decreed they were finished for the day and insisted they return to his stepbrother’s house. Her trunk had still not been located, but Suzette assured her it had probably simply been placed in the wrong room, more than likely in the wrong wing, and every effort was being made to find it. India wasn’t sure she completely believed the woman. What she’d seen of the household staff did not inspire confidence in their efficiency. It was not the least bit surprising that they had misplaced her trunk. However, she had to admit, the food here was excellent, if a bit rich. Still, there was too much on her mind to enjoy the meal or partake in the lively conversation. No one seemed to notice.

It was obvious that Estelle had fallen under the spell of both Derek and Lord Brookings, given the way the older lady fluttered her lashes and emitted the occasional giggle, not to mention the look of adoration in her eyes. As if she were a schoolgirl and not a woman in her late fifties.

Professor Greer seemed to have succumbed to their charms, as well, and much of the conversation consisted of reminiscences of his student days in Paris thirty-some years ago. The three men dedicated a considerable amount of time to comparing and contrasting the Paris of today—with its newly widened boulevards and recently constructed edifices—with the Paris of the professor’s youth. And as much as he appreciated the modern look of the city, he did speak longingly of twisted medieval streets, narrow passageways and ancient buildings. There was a touch of longing, as well, in his memories of some of the more unsavory entertainments Paris had offered, and Lord Brookings assured him some things never change. Thankfully, Derek quickly directed the conversation toward other topics.

No, India would have preferred to avoid dinner altogether and wouldn’t have minded avoiding Derek, as well. She had not been inebriated at the café, but the wine had served to loosen her tongue. But when she reflected upon their conversation, there was little she said that she would not have said without the wine. Although she probably owed him an apology. Her dismissal of his desire not to disappoint was beyond rude; it was petty of her and unkind. A distinct sense of shame washed through her at the thought. He’d been nothing but nice to her, and she’d returned his kindness with sarcasm and disdain. Indeed, she couldn’t help but wonder if he wasn’t quite the scoundrel she’d thought he was but rather misguided in his attempt to prove his worth. It was a thought worth further consideration.

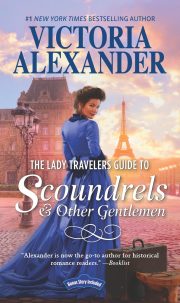

"The Lady Travelers Guide to Scoundrels and Other Gentlemen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Lady Travelers Guide to Scoundrels and Other Gentlemen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Lady Travelers Guide to Scoundrels and Other Gentlemen" друзьям в соцсетях.