Katherine’s early years with her parents who fought for every inch of their kingdom shows in every decision she and Thomas Howard make together. Though everyone left in England complains that they are guarded by an old man and a pregnant woman, I believe that these two are better commanders than those in France. She understands the dangers of a battle ground and the deploying of a troop as if it were the natural business of a princess. When Thomas Howard musters his men to march north, they have a battle plan that he will attack the Scots in the north, and she will hold a second line in the Midlands, in case of his defeat. It is she who defies her condition to ride out to the army on a white horse, dressed in cloth of gold, and bawls out a speech to tell them that no nation in the world can fight like the English.

I watch her, and I can hardly recognize the homesick girl who cried in my arms at Ludlow. She is a woman indeed, she is a queen. Better than that, she is a queen militant, she has become a great Queen of England.

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, AUTUMN 1513

Katherine is filled with bloodthirsty delight, and I laugh as she dances round the room, singing a battle song in Spanish. I take her hands and beg her to sit, be still and be calm; but she is completely her mother’s daughter, demanding that the head of James of Scotland be sent to her, until we persuade her that an English monarch cannot be so ferocious. Instead, she sends his bloodstained coat and torn banners to Henry in France, so that he shall know she has guarded the kingdom better than any regent has ever done before, that she has defeated the Scots as no one has ever done before, and London celebrates with the court that we have a heroine queen, a queen militant, who can hold the kingdom and carry a child in her womb.

She is taken ill in the night. I am sleeping in her bed and I hear her moan before the pain breaks through her sleep. I turn and raise myself up on one elbow to see her face, thinking that she is having a bad dream, and that I will wake her. Then I feel under my bare feet the wetness in the bed, and I flinch from the sensation, jump out of bed, pull back the sheets, and see my own nightgown is red, terribly stained with her waters.

I tear to the door and fling it open, screaming for her ladies and for someone to call the midwives and the physicians, and then come back to hold her hands as she groans as the pains start to come.

It is early, but it is not too early; perhaps the baby will survive this sudden urgent, fearful rush. I hold Katherine’s shoulders as she leans forward and then I sponge her face as she leans back and gasps with relief.

The midwives shout for her to push, and then suddenly they say, “Wait! Wait!” And we hear, we all can hear, a tiny gurgling cry.

“My baby?” the queen asks wonderingly, and then they lift him, his little legs writhing, the cord dangling, and rest him on her slack, quivering belly.

“A baby boy,” someone says in quiet wonderment. “My God, what a miracle,” and they cut the cord and wrap him tightly and then fold the warmed sheets across Katherine and put him into her arms. “A baby boy for England.”

“My baby,” she whispers, her face alight with joy and love. She looks, I think, like a portrait of the Virgin Mary as if she held the grace of God in her arms. “Margaret,” she says in a whisper. “Send a message to the king . . .”

Her face changes, the baby moves just slightly, his back arches, he seems to choke. “What’s the matter?” she demands. “What’s the matter with him?”

The wet nurse who was coming forward, undoing the front of her gown, rears back as if she is suddenly afraid to touch the child. The midwife looks up from the bowl of water and the cloth and lunges for him, saying, “Slap him on the back!” as if he has to be born and take his first breath all over again.

Katherine says: “Take him! Save him!” and bounds forward in the bed, thrusting him out to the midwife. “What’s wrong with him? What’s the matter?”

The midwife clamps her mouth over his nose and mouth, sucks and spits black bile on the floor. Something is wrong. Clearly, she does not know what to do, nobody knows what to do. The little body retches, a pool of something like oil spills from his mouth, from his nose, even from his closed eyes where little dark tears run down the tiny pale cheeks.

“My son!” Katherine cries.

They upend him like a drowned man from the moat, they slap him, they shake him, they put him over the nurse’s knees and pound his back. He is limp, he is white, his fingers and little toes are blue. Clearly he is dead and slapping will not return him to life.

She falls back on the bed, she pulls the covers over her face as if she wishes she were dead too. I kneel at the side of the bed and reach for her hand. Blindly, she grips me; “Margaret,” she says from under the covers as if she cannot bear that I should see her lips framing the words. “Margaret, write to the king and tell him that his baby is dead.”

As soon as the midwives have cleared up and gone, as soon as the physicians have given their opinion, which is nothing of any use, she herself writes to the king and sends the news by Thomas Wolsey’s messengers. She has to tell Henry, the homecoming conqueror in his moment of triumph, that although he has won proof of his valor; there is no proof of his potency. He has no child.

We wait for his return; she is bathed and churched and dressed in a new gown. She tries to smile, I see her practice before a mirror, as if she has forgotten how to do it. She tries to seem joyful for his victory, glad of his return, and hopeful for their future.

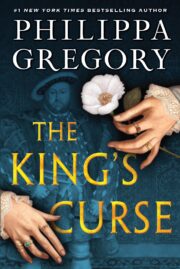

"The King’s Curse" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Curse". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Curse" друзьям в соцсетях.