The ladies of the queen’s chamber sew banners, keepsakes, and special shirts made from tough cloth to wear under chain mail; but Katherine, herself the daughter of a fighting queen, raised in a country at war, meets with Henry’s commanders and talks to them about provisions, discipline, and the health of the troops they will take to invade France. Only Wolsey understands her concerns, and she and the almoner are often closeted together, discussing routes for the march, provisions along the way, how to establish lines of messengers and how one commander can communicate with another and be persuaded to work together.

Thomas Wolsey treats her with respect, observing that she has seen more warfare than many of the noblemen at court, since she was raised at the siege of Granada. The whole court treats her with a secret smiling pride, for everyone knows that she is with child again, her belly starting to grow hard and curved. She walks everywhere, refusing to ride, resting in the afternoons, a plump, shining confidence about her.

CANTERBURY, KENT, JUNE 1513

The queen takes my hand as I kneel to pray beside her, and passes me her rosary, pressing it into my hand.

“What’s this?” I whisper.

“Hold it,” she says. “While I tell you something bad. I have to tell you something that will distress you.”

The sharp ivory crucifix digs into my palm like a nail. I think I know what she has to tell me.

“It’s your cousin Edmund de la Pole,” she says gently. “I am sorry, my dear. I am so sorry. The king has ordered that he be put to death.”

Even though I am expecting this, even though I have known it must come, even though I have waited for this news for years, I hear myself say: “But why? Why now?”

“The king could not go to war leaving a pretender in the Tower.” I can tell from the guilt in her face that she remembers the last pretender to the Tudor throne was my brother, killed so that she would come to England and marry Arthur. “I am so sorry, Margaret. I am so sorry, my dear.”

“He’s been imprisoned for seven years!” I protest. “Seven years and there has been no trouble!”

“I know. But the council advised it too.”

I bow my head as if in prayer, but I can find no words to pray for the soul of my cousin, dead under a Tudor axe, for the crime of being a Plantagenet.

“I hope you can forgive us?” she whispers.

Under the soaring chant of the Mass I can hardly hear her. I grip her hand. “It’s not you,” I say. “It’s not even the king. It’s what anyone would do to rid themselves of a rival.”

She nods, as if she is comforted; but I put my head in my hands and know that they have not rid themselves of Plantagenets. It is impossible to be rid of us. My cousin Edmund’s brother, Richard de la Pole, his heir, now the new pretender, has run away from England and is somewhere in Europe, trying to raise an army; and after him, there is another and another of us, unending.

DOVER CASTLE, KENT, JUNE 1513

I can think of nothing but my boys, especially my son Montague, whose duty will keep him at the king’s side and whose honor will take him into the heart of any battle. I wait till his warhorse is loaded on the ships and he comes to me and bends his knee for my blessing. I am determined to say a smiling good-bye, and try to hide my fear for him.

“But take care,” I urge.

“Lady Mother, I am going to war. I am not supposed to take care. It would be a very poor war if we all rode out taking care!”

I am twisting my fingers together. “Take care with your food at least, and don’t lie on wet ground. Make sure that your squire always puts a leather cloak down first. And never take your helmet off if you are anywhere near—”

He laughs and takes my hands in his own. “Lady Mother, I will come home to you!” He is young and lighthearted and thinks that he will live forever, and so he promises the thing that in truth he cannot: that nothing will ever hurt him, not even on a battlefield.

I snatch at a breath. “My son!”

“I’ll make sure Arthur is safe,” he promises me. “And I’ll come home safe and sound. Perhaps I shall capture French prisoners for ransom, perhaps I shall come home rich. Perhaps I shall win French lands and you will be able to build castles in France as well as England.”

“Just come home,” I say. “Not even new castles matter more than the heir.”

He bends his head for my blessing and I have to let him go.

The war goes better than anyone dreams possible. The English army, under the king himself, take Therouanne, and the French cavalry flee before them. My son Arthur writes to me that his brother has ridden like a hero and has been knighted by the king, for his bravery in battle. My son Montague is now Sir Henry Pole—Sir Henry Pole!—and he is safe.

RICHMOND PALACE, WEST OF LONDON, SUMMER 1513

The only man left in England able to command is Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, the old dog of war whom Henry left behind for his queen to deploy as she thinks best. The seventy-year-old warrior and the pregnant queen take over the presence chamber at Richmond, and instead of sheets of music and plans of dances spread on the table, there are maps of England and Scotland, lists of musters, and the names of landlords who will turn out their tenants for the queen’s war against Scotland. The queen’s ladies go through their household men and report on their border castles.

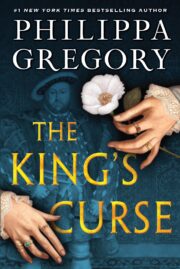

"The King’s Curse" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Curse". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Curse" друзьям в соцсетях.