I stand before him and I say the words that every condemned person is to say. I stress my loyalty to the king and recommend obedience to him. There is a moment when I feel like laughing out loud at this. How can anyone obey the king when his wishes change by the minute? How can anyone be loyal to a madman? I send my love and my blessings to the little Prince Edward, though I doubt that he will live to be a man, poor boy, poor accursed Tudor boy, and I send my love and blessings to the Princess Mary and I remember to call her Lady Mary and I say that I hope that she blesses me, who has loved her so dearly.

“That’s enough,” Philips interrupts. “I am sorry, your ladyship. You are not allowed to speak for long.”

The headsman steps forward and says: “Put your head on the block and stretch out your hands when you are ready for it, ma’am.”

Obediently, I put my hands on the block and awkwardly lower myself down to the grass. I can smell the scent of it under my knees. I am aware of the ache in my back and the sound of a seagull crying and someone weeping. And then suddenly, just as I am about to put my forehead against the rough top of the wooden block, and spread my arms wide to signal that he can strike, a rush of joy, a desire for life, suddenly comes over me, and I say: “No.”

It’s too late, the axe is up over his head, he is bringing it down, but I say: “No” and I sit up, and pull myself up on the block to get to my feet.

There is a terrible blow on the back of my head, but almost no pain. It fells me to the ground and I say “No” again, and suddenly I am filled with a great ecstasy of rebellion. I do not consent to the will of the madman Henry Tudor, and I do not put my head meekly down upon the block, and I never will. I am going to fight for my life and I say “No!” as I struggle to rise, and “No” as the blow comes again, and “No” as I crawl away, blood pouring from the wound in my neck and my head, blinding me but not drowning my joy in fighting for my life even as it is slipping away from me, and witnessing, to the very last moment, to the wrong that Henry Tudor has done to me and mine. “No!” I cry out. “No! No! No!”

Indeed, the more I have studied and thought about her life and her wide-ranging family, the Plantagenets, the more I have had to wonder if she was not at the center of conspiracy: sometimes actively, sometimes quietly, perhaps always conscious of her family’s claim to the throne, and always with a claimant in exile, preparing to invade, or under arrest. There was never a time when Henry VII or his son were free from fear of a Plantagenet claimant, and although many historians have seen this as Tudor paranoia, I wonder if there was not a constant genuine threat from the old royal family, a sort of resistance movement: sometimes active but always present.

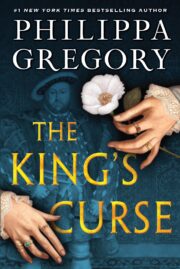

"The King’s Curse" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Curse". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Curse" друзьям в соцсетях.