And then, just after Terce, the doors to the street are flung open and the yeomen of the guard march into the entrance hall, to arrest my son Montague.

We were going to breakfast, and Montague turns as the golden leaves from the vine blow in from the street about the feet of the guards. “Shall I come at once, or take my breakfast first?” he asks, as if it is a small matter of everyone’s convenience.

“Better come now, sir,” the captain says a little awkwardly. He bows to me and to Constance. “Begging your pardon, your ladyship, my lady.”

I go to Montague. “I’ll get food and clothing to you,” I promise him. “And I’ll do what I can. I’ll go to the king.”

“No. Go back to Bisham,” he says quickly. “Keep far away from the Tower. Go today, Lady Mother.”

His face is very grave; he looks far older than his forty-six years. I think that they took my brother when he was only a little boy, and killed him when he was a young man; and now here is my son, and it has taken all this long time, all these many years, for them to come for him. I am dizzy with fear, I cannot think what I should do. “God bless you, my son,” I say.

He kneels before me, as he has done a thousand, thousand times, and I put my hand on his head. “God bless us all,” he says simply. “My father lived his life trying to avoid this day. Me too. Perhaps it will end well.”

And he gets up and goes out of the house without a hat or a cape or gloves.

I am in the stable yard, watching them pack the wagons for us to leave, when one of the Courtenay men brings me a message from Gertrude, wife to Henry Courtenay, my cousin.

They have arrested Henry this morning. I will come to you when I can.

I cannot wait for her, so I tell the guards and the household wagons to go ahead, down the frozen roads to Warblington, and that I will follow later on my old horse. I take half a dozen men and my granddaughters Katherine and Winifred and ride through the narrow streets to Gertrude’s beautiful London house, the Manor of the Rose. The City is getting ready for Christmas, the chestnut sellers are standing behind glowing braziers stirring the scorching nuts and the evocative scents of the season—mulled wine, cinnamon, woodsmoke, burnt sugar, nutmeg—are hanging in trails of gray smoke on the frosty air.

I leave the horses at the great street door, and my granddaughters and I walk into the hall and then into Gertrude’s presence chamber. It is oddly quiet and empty. Her steward comes forward to greet me.

“Countess, I am sorry to see you here.”

“Why?” I ask. “My cousin Lady Courtenay was coming to see me. I have come to say good-bye to her. I am going into the country.” Little Winifred comes close to me and I take her small hand for comfort.

“My lord has been arrested.”

“I knew that. I am certain that he will be released at once. I know that he is innocent of anything.”

The steward bows. “I know, my lady. There is no more loyal servant to the king than my lord. We all know that. We all said that, when they asked us.”

“So where is my cousin Gertrude?”

He hesitates. “I am sorry, your ladyship. But she has been arrested too. She has gone to the Tower.”

I suddenly understand that the silence of this room is filled with the echoes of a place that has been abruptly cleared. There are pieces of needlework on the window seat, and an open book on the reader in the corner of the room.

I look around and I realize that this tyranny is like the other Tudor disease, the Sweat. It comes quickly, it takes those you love without warning, and you cannot defend against it. I have come too late, I should have been earlier. I have not defended her, I did not save Montague, or Geoffrey. I did not speak up for Robert Aske, nor for Tom Darcy, John Hussey, Thomas More, nor for John Fisher.

“I’ll take Edward home with me,” I say, thinking of Gertrude’s son. He is only twelve, he must be frightened. They should have sent him to me at once, the minute his parents were arrested. “Fetch him for me. Tell him that his cousin is here to take him home while his mother and father are detained.”

Inexplicably, the steward’s eyes fill with tears, and then he tells me why the house is so quiet. “He’s gone,” he says. “They took him too. The little lord. He’s gone to the Tower.”

WARBLINGTON CASTLE, HAMPSHIRE, AUTUMN 1538

“What is it?”

His face is scowling with worry. “The Earl of Southampton and the Bishop of Ely to see you, my lady,” he says.

I rise to my feet, putting my hand to the small of my back where a nagging pain comes and goes with the weather. I think briefly, cravenly, how very tired I am. “Do they say what they want?”

He shakes his head. I force myself to stand very straight, and I go out into my presence chamber.

I have known William Fitzwilliam since he played with Prince Henry in the nursery, and now he is a newly made earl. I know how pleased he will be with his honors. He bows to me but there is no warmth in his face. I smile at him and turn to the Bishop of Ely, Thomas Goodrich.

“My lords, you are very welcome to Warblington Castle,” I say easily. “I hope that you will dine with us? And will you stay tonight?”

William Fitzwilliam has the grace to look slightly uncomfortable. “We are here to ask you some questions,” he says. “The king commands that you answer the truth upon your honor.”

I nod, still smiling.

“And we will stay until we have a satisfactory answer,” says the bishop.

“You must stay as long as you wish,” I say insincerely. I nod to my steward. “See that the lords’ people are housed, and their horses stabled,” I say. “And set extra places at dinner, and the best bedchambers for our two honored guests.”

He bows and goes out. I look around my crowded presence chamber. There is a murmur, nothing clear, nothing stated, just a sense that the tenants and petitioners in the room do not like the sight of these great gentlemen riding down from London to question me in my own house. Nobody speaks a disloyal word but there is a rustle of whispers like a low growl.

William looks uneasy. “Shall we go to a more convenient room?” he asks.

I look around and smile at my people. “I cannot talk with you today,” I say clearly, so that the poorest widow at the back can hear. “I am sorry for that. I have to answer some questions for these great lords. I will tell them, as I tell you, as you know, that neither I nor my sons have ever thought, done, or dreamed anything which was disloyal to the king. And that none of you has ever done anything either. And none of us ever will.”

“Easily said,” the bishop says unpleasantly.

“Because true,” I overrule him, and lead the way into my private room.

Under the oriel window there is a table where I sometimes sit to write, and four chairs. I gesture that they may sit where they please, and take a chair myself, my back to the wintry light, facing the room.

William Fitzwilliam tells me, as if it were a matter of mild interest, that he has been questioning my sons Geoffrey and Montague. I nod at the information, and I ignore the swift pang of murderous rage at the thought of this upstart interrogating my boys, my Plantagenet boys. He says that they have both spoken freely to him; he implies he knows everything about us, and then he presses me to admit that I have heard them speak against the king.

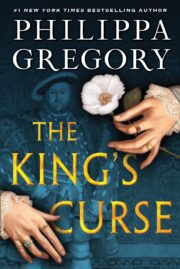

"The King’s Curse" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Curse". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Curse" друзьям в соцсетях.