“He’d never say anything that would hurt us,” I say. I find I am smiling, even in this danger, at the thought of my son’s loving, faithful heart. “He’d never say anything that would hurt any of us.”

“No, and besides, at the very worst, all we have done is warn a brother that he is in danger. Nobody could blame us for that.”

“What can we do?” I ask. I want to rush to the Tower at once, but my knees are weak, and I can’t even rise.

“We’re not allowed to visit; only his wife can go into the Tower to see him. So I’ve sent for Constance. She’ll be here tomorrow. And after she’s seen him and made sure that he’s not said anything, I’ll go to Cromwell again. I might even speak with the king when he comes back, if I can catch him in a good mood.”

“Does Henry know of this?”

“It’s my hope he knows nothing. It might be that Cromwell has overreached himself and that the king will be furious with him when he finds out. His temper is so unreliable these days that he lashes out at Cromwell as often as he agrees with him. If I can catch him at the right time, if he is feeling loving towards us, and irritated by Cromwell, he might take this as an insult to us, his kinsmen, and knock Cromwell down for it.”

“He is so changeable?”

“Lady Mother, none of us ever knows from dawn to dusk what mood he will be in, nor when or why it will suddenly change.”

I spend the rest of the evening and most of the night on my knees in my chapel, praying to my God for the safety of my son; but I can’t be sure that He is listening. I think of the hundreds, thousands of mothers on their knees in England tonight, praying for the safety of their sons, or for the souls of their sons who have died for less than Geoffrey and Montague have done.

I think of the abbey doors banging open in the moonlight of the English summer night, of the sacred chests and holy goods tumbled onto shining cobbles in darkened squares as Cromwell’s men pull down the shrines and throw out the relics. They say that Thomas Becket’s shrine, which the king himself approached on his knees, has been broken up and the rich offerings and the magnificent jewels have disappeared into Lord Cromwell’s new Court of Augmentations, and the saint’s sacred bones have been lost.

After a little while I sit back on my heels and feel the ache in my back. I cannot bring myself to trouble God; there is too much for Him to put right tonight. I think of Him, old and weary as I am old and weary, feeling as I do, that there is too much to put right and that England, His own special country, has gone all wrong.

L’ERBER, LONDON, AUTUMN 1538

“I’ve never seen him like this before,” she says. “I don’t know what I can do.”

“What is he like?” Montague asks gently.

“Crying,” she says. “Raging round the room. Banging on the door but no one comes. Taking hold of the bars of the window and shaking them as if he thinks he might bring down the walls of the Tower. And then he turned and fell on his knees and wept and said he could not bear it.”

I am horrified. “Have they hurt him?”

She shakes her head. “They’ve not touched his body—but his pride . . .”

“Did he say what they put to him?” Montague asks patiently.

She shakes her head. “Don’t you hear me? He’s raving. He’s in a frenzy.”

“He’s not coherent?”

I can hear the hope in Montague’s voice.

“He’s like a madman,” she says. “He’s praying and crying, and then he suddenly declares that he’s done nothing, and then he says that everyone always blames him, and then he says he should have run away but that you stopped him, that you always stop him, and then he says that he cannot stay in England anyway for the debts.” Her eyes slide to me. “He says that his mother should pay his debts.”

“Could you tell if he has been properly questioned? Has he been charged with any offense?”

She shakes her head. “We have to send him clothes and food,” she says. “He’s cold. There’s no fire in his room, and he has only his riding cape. And he threw that down on the floor and stamped on it.”

“I’ll do that at once,” I say.

“But you don’t know if he has been properly questioned, nor what he has said?” Montague confirms.

“He says that he has done nothing,” she repeats. “He says that they come and shout at him every day. But he says nothing for he has done nothing.”

Geoffrey’s ordeal goes on another day. I send my steward with a parcel of his warm clothes and with orders to buy food from the bakehouse near the Tower and take in a proper meal for my boy, although he comes back and says that the guards took the clothes but he thought they would keep them, and that he was not allowed to order a meal.

“I’ll go with Constance tomorrow, and see if I can command them to take him a dinner at least,” I say to Montague, as I enter the echoing presence chamber at L’Erber. It is empty of anyone, no petitioners, no tenants, no friends. “And she can take in a winter cape and some linen for him, and some bedding.”

He is standing at the window, his head bowed, in silence.

“Did you see the king?” I ask him. “Could you speak to him for Geoffrey? Did he know that Geoffrey is under arrest?”

“He knew already,” Montague says dully. “There was nothing I could say, for he knew already.”

“Cromwell acted with his authority?”

“That we’ll never know. Lady Mother. Because the king didn’t know about Geoffrey from Cromwell. He knew from Geoffrey himself. Apparently, Geoffrey has written to him.”

“Written to the king?”

“Yes. Cromwell showed me the letter. Geoffrey wrote to the king that if the king will order him some comforts, then he will tell all he knows, even though it touches his own mother, or brother.”

For a moment I hear the words but I cannot make out the meaning. Then I understand. “No!” I am horror-struck. “It can’t be true. It must be a forgery. Cromwell must be tricking you! It’s what he would do!”

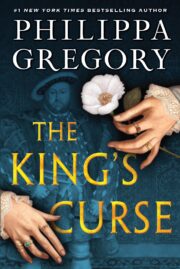

"The King’s Curse" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Curse". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Curse" друзьям в соцсетях.