Thus I returned to London for the first time since Edward’s funeral. It seemed to me a much longer stretch of time than the actual weeks since I had fled from the door of the Abbey with Joan’s triumphant prediction resounding in my ears. Momentarily my spirits leaped at the familiar noise and bustle, the sight of wealthy merchants and their wives in as much finery as Edward’s sumptuary laws would allow. The glimpse of the Thames between warehouses, opaque like gray glass in the winter air, drew me. I was not a natural country dweller and never would be—then I recalled with a cold squeeze of a hand around my heart that I was not here for the pleasures that London could offer.

I touched Windsor’s arm for reassurance, grateful when he covered my hand with his own. If affairs went badly for me, I might spend my days in a dungeon or banished from the realm. Or worse…Trying to reply to some bland comment made by Windsor as we wove a path between beggars and whores and the dregs of the London gutters that milled by the waterside, I swallowed against a knot of pure terror.

Dismounting at the Palace of Westminster, Windsor took charge of our horses and I questioned one of the officials. Where were the Lords intending to meet? I was directed to a chamber that Edward had sometimes used for formal audiences, such as the visit of the three kings so many years ago. So this too was to be very formal. But then there was no time to think. Windsor was pulling at my mantle and we walked briskly toward my fate. Guards barred our way at the door; the lords were not yet assembled. Impatiently, I turned to see a man sitting on one of the benches usually occupied by petitioners, waiting for us.

“Wykeham.” Windsor nodded briefly.

“Windsor,” Wykeham reciprocated.

The two men eyed each other with little warmth. That would never change.

“I thought that you of all people would have kept clear of this place,” I said, to hide my astonishment that the bishop should be here. “It’s not politic for a sensible man to be seen in my company.”

“You forget.” His grimace as he kissed my fingers was a praiseworthy attempt at a smile. “I’m a free man, pardoned and reinstated. I shine with honest rectitude. Parliament in its wisdom has turned its smiling face on me, so nothing can touch me.”

I had never heard him so cynical. “I hope I can say the same for myself after today, but I am not confident.”

“I expect you can talk them ’round.” His mordant humor had an edge. Warmed by his attempt to reassure me, however much an empty gesture it proved to be, I asked what I had never asked before.

“Pray for me, Wykeham.”

“I will. Even though I’m not sure it matters to you. You spoke for me when I needed it.” He pressed my fingers before releasing them. “I’ll do what I can, lady. The Lords might listen if I speak for you.…”

The unusual term of respect from Wykeham almost brought me to tears, and I curtsied deeply to him, as I had never done before.

“You have some strange friends, my love,” Windsor observed when Wykeham was gone. “The man—priest or not—is enamored of you. God help him!”

“Nonsense!” I replied, marshaling my scattered emotions. “I helped to get him dismissed.”

“And you reunited him with Edward. You are too hard on yourself.” He folded my hands in his and kissed my lips, my cheeks. “Remember what I told you,” he whispered against my temple.

And then I was on my own.

Without any fuss or fanfare, I was shown into the chamber. There was no chair placed for me this time: I was expected to stand throughout. Before me and beside me, on three sides, the ranks of hostile faces stared their enmity, just as I had imagined. And in the end Windsor could not keep his promise to be with me—he was barred at the door. He did not bother to argue when faced with the point of the guards’ halberds. I could imagine him pacing the chamber outside to no avail.

I looked ’round at those I knew and those I did not. Would there be justice? I thought not.

Be calm. Be reasoned. Be aware. Don’t allow yourself to be tricked into any admission that can be used against you. Tell the truth as much as you can. Use the intelligence God gave you. And don’t speak out of turn or with misplaced arrogance.

Windsor had been brutal in his advice.

But I was so alone. Even his love could not still the rapid trip of my heart.

“Mistress Perrers.”

I looked up sharply. Their spokesman, a sheaf of pages in his hand, was Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, Marshal of England. A close associate of Gaunt. I did not like this. I did not like it at all, but I clung to my resolve and I inclined my head.

“My lord.”

“You are summoned here to answer to charges of a most serious nature. Do you understand?”

So that was how it would be. Formal and legal, entirely impersonal. I still did not know what the charges were.

“Yes, my lord. I understand.”

“We require you to answer questions concerning your past conduct. There are outstanding charges against you.”

“And they are?” Fear bloomed against all my desires.

“Fraud, mistress. And treason. How do you plead?”

“Innocent,” I replied instantly. “To both. And I question the validity of any evidence against me.” I might be circumspect in my replies, but I would not be a fool. I knew what they were about, concocting some spurious occasion on which I had committed treason. Even fraud was a matter for debate.

“They are serious charges, mistress. Perhaps you should take time to consider.…”

“In what manner have I ever committed fraud?” I kept my voice clear and strong and confident, my spine straight as a halberd staff. “I have never used dishonest deception or trickery to benefit myself. I have never used false representations. If you are questioning my holding of royal manors, they were freely given to me by King Edward, gifts of his generosity, out of his affection for me.” Let them accept that statement! “Those I purchased in my own name were done so openly and legally, through the offices of my agent. I utterly deny the charge of fraud, my lords.”

My breathing, with great effort, was slow and controlled, my voice even and commanding. What evidence could they possibly have?

“But in the matter of treason, mistress…”

“Treason? On which occasion did I violate my sworn allegiance to my King?” I was on firm ground here. Not even this august body could find evidence of my bringing the state of the King into danger. “I challenge you to find any evidence of my being a danger either to the King’s health or to the security of the realm.” Perhaps not wise, but fear compelled me to state my case so bluntly. I appraised the faces turned toward me. Some met my gaze; some looked anywhere but at me. “Well, my lords? Where is your evidence?”

The Lords moved uneasily on their benches, whispered together. Northumberland shuffled his documents.

“We must deliberate, mistress. If you would wait in the antechamber?”

I stalked out.

“What’s happening?” Windsor was immediately there, drawing me to sit on the bench recently vacated by Wykeham.

“They are deliberating.”

“What, in God’s name? You were barely in there for five minutes!”

“I don’t know.” I could not sit, but prowled across the width of the room and back.

“I presume it’s not going well?”

“Nothing is going well. They charged me, but refused to produce any evidence against me. What do I make of that? If they have no evidence, why call me here? I am afraid, Will. I’m afraid of what I don’t know.”

“I wish I could be there with you.” He rose to prowl with me.

“I know.” I leaned into him. “But I don’t think it would do any good. Even the Archangel Gabriel himself could not keep the Lords from my tearing out my throat.”

Within the half hour I was called back.

“Mistress Perrers,” Northumberland said, with a self-satisfied air. “The Lords have debated the evidence against you. That you did wantonly and deliberately disobey the orders issued by the Good Parliament.”

What was this? A completely new direction? Fraud and treason had suddenly been abandoned, unless it was treason to disobey Parliament. In that moment I realized that the Lords had known from the beginning that these charges were untenable. But what was the implication here? I felt the ground shift under my feet. This was far more dangerous, a presentiment of it shivering along my spine. How I wished for Windsor’s strength beside me.

“Which orders?” I asked, genuinely puzzled. Had I not obeyed them to the letter? Surely this could not be witchcraft again? Nausea gripped my belly.

“The orders that banished you from the person of the King and from living anywhere in the vicinity of the royal Court…”

But had I not done what they asked of me?

“I reject that accusation.”

“Do you?” A complacent curve of Northumberland’s mouth attested to his certainty that my denial would hold no weight. “You were banished—and yet you returned to be with His late Majesty in the weeks before his death.…”

Be calm! They cannot prove your guilt on this.…

“I observed the orders,” I stated, choosing my words with care, whilst my heart galloped like a panicked horse. “I lived in retirement. I did not return to Court until my lord of Gaunt had the orders against me rescinded. I state this, a fact that must be well-known to all here present, as proof of my innocence.”

“This Chamber knows nothing of that. It believes that you are guilty of breaking the terms of your banishment by Parliament. A most heinous crime.”

“No! I did not! I was informed by the hand of my lord of Gaunt himself that I was free to return.”

“And you have proof of this?”

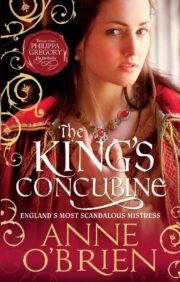

"The King’s Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.