The rain and winds abating, the roads were soon open again, and the Thames was once more busy with river traffic, so we heard of events in London and elsewhere. Some of them encroached on my existence not at all. How strange that was.

The boy Richard, clad in white and gold, was crowned on the sixteenth day of July. A Thursday, forsooth! Unusual, but chosen as the auspicious Eve of St. Kenelm, an undistinguished but martyred child King of the old Kingdom of Mercia.

“Doubtless Fair Joan thought the lad needed all the happy auguries he could get,” Windsor growled.

Which was a sound assessment. There were troubles afoot. In the absence of a strong English army with a king at its head, the French had seized the initiative with numerous incursions along the south coast of England, burning and pillaging all they came upon. The town of Rye became an inferno. Some French marauders even reached Lewes. In Pallenswick we felt safe enough.

How strange to have no association with such momentous events, to be entirely divorced from the King’s plans to drive the French out. Who would take on the direction of foreign policy? Gaunt, I supposed. I closed my mind to it, for it no longer touched me.

But some events, through association, touched me closely.

Wykeham, my dear Wykeham, was formally pardoned, thus confirming the healing of the wounds between Edward and his former Chancellor. At least I had been able to achieve that much for an old friend. Wykeham wrote:

I am restored to grace, but not to political office. I shall turn my mind to the matter of education at Oxford with the building of two new colleges. I know that will appeal to you—although no woman will set foot within their doors! I might owe you that—but we must both accept that it cannot be done.

It made me smile. How difficult for a priest to acknowledge a debt to a sinful daughter of Eve, but he had done it, and with such elegance. I wished him well. I thought we were unlikely to meet again.

Finally, there came some unsettling news that made me laugh—and then frown. With the meeting of Parliament, Gaunt was invited to join a committee of the Lords to deal with the threats from across the Channel.

“So, Gaunt’s star is in the ascendant,” Windsor remarked, reading Wykeham’s letter over my shoulder.

“To be expected,” I replied. “He has the blood and the experience.”

“Unfortunately no reputation for success!”

Windsor’s contempt did not disturb me. What would Gaunt’s waxing power mean for me now? Our ambitions no longer ran in parallel lines. But Windsor was thoughtful, taking Wykeham’s letter to reread at his leisure. It always worried me when he felt the need to brood over a cup of ale.

But I laughed when I read of Parliament’s outrageously high-handed petition to young Richard. How predictable of them! In the future, only Parliament should have the right to appoint Richard’s Chancellor, Treasurer, and every other high office of state they could discover. Parliament would control the King at every step. No one was ever to be allowed to do what I had done when Edward was too ill to do it for himself. There would never be another Alice Perrers, ruling the royal roost.

Yes, I laughed, but there was not much humor in it.

I found nothing to laugh at afterward. A heavy hammering on my door at Pallenswick, much like the thump of a mailed fist, brought me hotfoot from my receipts and estate records. Windsor, I knew, was engaged in draining water meadows over at Gaines. Nor would I expect him to knock on my door when he returned—we still led a strange peripatetic life, in no sense a united household, as if our marriage were still some unshaped business entity that sometimes demanded our intimacy and sometimes did not. No, Windsor would not knock. Rather he would fling the door wide and stride inside, his voice raised to announce his arrival, filling the house with his formidable, restless presence. This was not Windsor. My heart tripped with a fast rebirth of the fear that always lurked deep within me, but I would not hide.…I strode toward the repeated thud.

“A group of men, mistress.” My steward hovered uncertainly in the entrance hall. “Do I open to them?”

“Do so.” If this was a threat, I would face it.

“Good day, mistress.”

Not a mailed fist, but a staff of office, and potentially just as forceful. The man at my door was clothed in the sober garments of an upper servant: a clerk or a gentleman’s secretary. Or, a breath of warning whispering over my neck, a Court official. I did not know him. I did not like the look of him, despite his mild expression and his courteous bow, or the dozen men at his back. My courtyard was crowded with pack animals and two large wagons.

“Mistress Perrers?”

“I am. And who are you, sir?” I asked with careful good manners.

All had been quiet on the London front over the past months, Richard getting used to the weight of the crown and Joan queening it over the Court. I had not stirred from my self-imposed exile.

“Keep your head down,” Windsor had advised after my previous flirtation with danger. “They’ve too many problems to be concerned about you. Defense of the realm has taken precedence over the old King’s mistress. Another few months and you’ll be forgotten.”

“I don’t know if I like that thought.” Obscurity did not sit well with me. “Do I want to be forgotten?”

“You do if you’ve any sense. Stay put, woman.”

So I had, and as the weeks had passed with no further evidence of Joan’s malevolence, my dread had abated. But if Windsor was well-informed, as he usually was, what was this on my doorstep? It did not bode well. Mentally I cursed Windsor for his overconfidence, and for his absence. Why was a man never around when you needed him? And why should I need him, anyway? Could I not deal with this encroachment on my own property? I eyed my visitor. This man in his black tunic and leather satchel carried far too much authority for my liking. My throat dried as his flat stare moved over me from head to toe.

But they cannot arrest you. You have committed no crime. Gaunt stood for you! He rescinded the banishment!

I breathed a little more easily.

The official bowed again. At least he was polite, but his men had an avaricious gleam.

“I am Thomas Webster, mistress.” From the satchel, he took a scroll. “I am sent by a commission appointed by Parliament.” Soft-voiced and respectful despite those assessing eyes, he held out the document for me to take. I did so, unrolling it between fingers that I held steady as I scanned the contents. It was not difficult to absorb the gist of it within seconds.

My breathing was once more compromised. My hand crushed one of the red seals that spoke of its officialdom, and I pretended to read through it again whilst I forced a deep breath into my lungs. Then I stood solidly on my doorstep, as if it would be possible for me to block their entry.

“What’s this? I don’t understand.” But the words were black and clear before my eyes.

“I am given authority to take what I can of value, mistress.”

The beat of my heart in my throat threatened to choke me. “And if I refuse?”

“I wouldn’t if I were you, mistress,” he said dryly. “You’ve not the power to stop me. I have a list of the most pertinent items. Now, if you will allow me…?”

So they came in with a heavy clump of boots, Webster unfolding his abomination of a list. It was an inventory of all I owned, everything that Pallenswick contained that belonged to me.

Panic built, roaring out of control.

“The house is mine!” I objected. “It is not Crown property. It was not a gift from the King—I bought it.”

“But bought with whose money, mistress? Where did that money come from?” He might have smirked. “And whose are the contents? Did you buy those too?” He turned his back on me, beckoning to his minions to begin their task.

There was no answer I could give that would make any impression. I stood and watched as the order of Parliament’s commission was instigated. All my property was hauled out before me into the courtyard and stowed in the wagons and on the pack animals. My linen, my furniture, even my bed. Jewels, clothing, trinkets, and through it all Webster reading from his despicable list.

“A diadem of pearls. A gold chain set with rubies. A yard of scarlet silk ribbon. A pair of leather gloves, the gauntlets embroidered in silver and…”

“A yard of ribbon…?” A cry touching on hysteria gathered in my throat.

“Every little helps, mistress. We have a war to fund,” he replied caustically. “Those jewels will fetch by our reckoning close to five hundred pounds. Better a well-armed body of men to defend English soil than these pretty things ’round your neck!”

It was useless. I watched in silence as everything was carried out of my house. When I saw the robes clutched in the arms of a burly servant, a heap of fur and silk and damask in rich blue and silver, the robes that Edward had had made for me for a second great tournament at Smithfield, I choked back the tears. They had never been worn; that second tournament was never held. The robes were cast on the wagon with all the rest.

And there I was, left to stand in the empty entrance hall of my own house.

“Have you finished?”

“Yes, mistress. But I should warn you: Parliament has taken on the burden of your creditors. Any man with a claim against you is invited to put forward his demands.”

“My creditors?” It grew worse and worse.

“Indeed, mistress. Any man with a grievance for extortions or oppressions or injuries committed by yourself”—how he was enjoying this!—“can appeal to Parliament for redress.”

“Where…where did this order come from?” I demanded. Oh, I knew the answer!

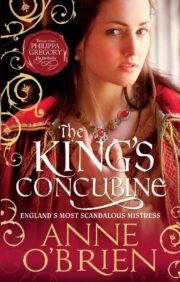

"The King’s Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.