The noisome, overcrowded squalor of London shocked me. The environs of Barking Abbey, bustling as they might be on market day, had not prepared me for the crowds, the perpetual racket, the stench of humanity packed so close together. But equally the city fascinated me: I did not know where to look next. At close-set houses in streets barely wider than the wagon, where upper stories leaned drunkenly to embrace one another, blocking out the sky. At shop frontages that displayed the wares, at women who paraded in bright colors. At scruffy urchins and bold prostitutes who carried on a different business in the rank courts and passageways. It was a new world, both frightening and seductive: I stared and gawped, as naive as any child from the country.

“Here’s where you get off.”

The wagon lurched and I was set down, directed by a filthy finger that pointed at my destination, a narrow house taking up no space at all, but rising above my head in three stories. I picked my way through the mess of offal and waste in the gutters to the door. Was this the one? It did not seem to be the house of a man of means. I knocked.

A woman, far taller than I, thin as a willow lath with her hair scraped into a pair of metallic cylindrical cauls on either side of her gaunt face, as if she were encased in a cage, opened it. “Well?”

“Is this the house of Janyn Perrers?”

“What’s it to you?”

Her gaze flicked over me, briefly. She made to close the door. Forsooth, I could not blame her: I saw myself through her eyes. My borrowed overgown had collected a multitude of creases and any amount of woolen fiber. I was not an attractive object. But this was where I had been sent, where I was expected. I would not have the door shut in my face.

“I have been sent!” I said, slapping my palm boldly against the wood.

“What do you want?”

“I am Alice,” I said, remembering, at last, to curtsy.

“If you’re begging, I’ll take my brush to you.…”

“I’m sent by the nuns at the Abbey,” I stated with a confidence I did not feel.

The revulsion in her stare deepened, and the woman’s lips twisted like a hank of rope. “So you’re the girl. Are you the best they could manage?” She flapped her hand when I opened my mouth to reply that yes, I supposed I was the best they could offer, since I was the only novice. “Never mind. You’re here now, so we’ll make the best of it. But in future you’ll use the door at the back beside the privy.”

And that was that.

I had become part of a new household.

And what an uneasy household it was. Even I, with no experience of such, was aware of the tensions from the moment I set my feet over the threshold.

Janyn Perrers: master of the house, pawnbroker, moneylender, and bloodsucker. His appearance did not suggest a rapacious man, but then, as I rapidly learned, it was not his word that was the law within his four walls. Tall and stooped, with not an ounce of spare flesh on his frame, and a foreign slur to his English usage, he spoke only when he had to, and then not greatly. In his business dealings he was unnervingly painstaking. Totally absorbed, he lived and breathed the acquisition and lending at extortionate rates of gold and silver coin. His face might have been kindly, if not for the deep grooves and hollow cheeks more reminiscent of a death’s head. His hair, or lack of, some few greasy wisps around his neck, gave him the appearance of a well-polished egg when he removed his felt cap. That was rare, as if he regretted his loss. I could not guess his age, but he seemed very old to me, with his uneven gait and faded eyes. His fingers were always stained with ink, his mouth too when he forgot and chewed his pen.

He nodded to me when I served supper, placing the dishes carefully on the table before him: It was the only sign that he noted a new addition to his household. This was the man who now employed me and would govern my future.

The power in the house rested on the shoulders of Damiata Perrers, the sister, who had made my lack of welcome patently clear. The Signora. There was no kindness in her face. She was the strength, the firm grip on the reins, the imposer of punishment on those who displeased her. Nothing happened within that house without her knowledge or permission.

There was a boy to haul and carry and clean the privy, a lad who said little and thought less. He led a miserable existence, but his face was closed to any offers of communication. He gobbled his food with filthy fingers and bolted back to his own pursuits in the nether regions of the house. I didn’t learn his name.

Then there was Master William Greseley, who was and was not of the household, since he spread his services farther afield, an interesting man who attracted my attention but ignored me with a remarkable determination. He was a clerk, a clever individual with black hair and brows, sharp features much like a rat, and a pale face as if he never saw the light of day, a man with as little emotion about him as one of the flounders brought home by Signora Damiata on market day. He ate and slept and noted down the business of the day. Ink might stain Master Perrers’s fingers, but I swore that it ran in Master Greseley’s veins. He wrote a fine hand and could guide a quill up and down the columns of figures, counting with impressive acumen. He disregarded me to the same extent that he was deaf to the vermin that scuttled across the floor of the room in which he kept the books and ledgers of money lent and reclaimed. I did not like him. There was a coldness to him that I found unpalatable.

And then there was me. The maidservant who undertook all the work not assigned to the boy. And some that was.

Thus my first introduction to the Perrers family. And since it was a good score of miles from Barking Abbey, it was not beyond my tolerance.

“God help th’man who weds you, mistress…!”

“I’m not going to be married!”

My vigorous assertion returned to mock me. Within a sennight I found myself exchanging vows at the church door.

Given the tone of her language, Signora Damiata was as astonished as I, and brutally forthright when I was summoned to join brother and sister in the parlor at the rear of the house, where, by the expression on the lady’s face, Master Perrers had just broken the news of his intent.

“Blessed Mary! Why marry?” she demanded. “You have a son, an heir, learning the family business in Lombardy. I keep your house. You want a wife at your age?” Her accent grew stronger, the syllables hissing over one another.

“I wish it.” Master Perrers continued leafing through the pages of a small ledger he had taken from his pocket.

“Then choose a daughter of one of our merchant families. A girl with a dowry and a family with some standing. Jesu! Are you not listening?” She raised her fists as if she might strike him. “This one is not a suitable wife for a man of your importance.”

Did I think that he did not rule the roost? On this occasion I could not have been more mistaken. He looked briefly at me. “I will have her. I will wed her. That is the end of the matter.”

I, of course, was not asked. I stood in this three-cornered dialogue yet not a part of it, the bone squabbled over by two dogs. Except that Master Perrers did not squabble. He simply stated his intention until his sister closed her mouth and let it be. So I was wed in the soiled skirts in which I chopped the onions and gutted the fish. Clearly there was no money earmarked to be spent on a new wife. Sullen and resentful, shocked into silence, certainly no joyful bride, I complied because I must. I was joined in matrimony with Janyn Perrers on the steps of the church, with witnesses to attest the deed. Signora Damiata, grim faced and silent; Master Greseley, because he was available, with no expression at all. A few words muttered over us by a bored priest in an empty ritual, and I was a wife.

There was little to show for it.

No celebration, no festivity, no recognition of my change in position in the household. Not even a cup of ale and a bride cake. It was, I realized, nothing more than a business agreement, and since I had brought nothing to it, there was no need to celebrate it. All I recall was the rain soaking through my hood as we stood and exchanged vows and the shrill cries of lads who fought amongst themselves for the handful of coin that Master Perrers scattered as a reluctant sign of his goodwill. Oh, and I recall Master Perrers’s fingers gripping hard on mine, the only reality in this ceremony that was not at all real to me.

Was it better than being a Bride of Christ? Was marriage better than servitude? To my mind there was little difference. After the ceremony I was directed to sweep down the cobwebs that festooned the storerooms in the cellar. I took out my bad temper with my brush, making the spiders run for cover.

There was no cover for me. Where would I run?

And beneath my anger was a lurking fear, for the night, my wedding night, was ominously close, and Master Perrers was no handsome lover.

The Signora came to my room that was hardly bigger than a large coffer, tucked high under the eaves, and gestured with a scowl. In a shift and bare feet I followed her down the stairs. Opening the door to my husband’s bedchamber, she thrust me inside, still without a word, and closed it at my back. I stood just within, not daring to move. My throat was so dry I could barely swallow. Apprehension was a rock in my belly, and fear of my ignorance filled me to the brim. I did not want to be here. I did not want this. I could not imagine why Master Perrers would want me, plain and unfinished and undowered as I was. Silence closed ’round me—except for a persistent scratching like a mouse trapped behind the plastered wall.

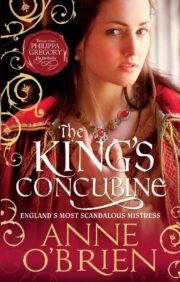

"The King’s Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.