He called Gaunt’s bluff, and it put the fear of God into me. This was a dangerous game de la Mare was playing, and one without precedent, as he challenged royal power. I would not wager against his victory.

Oh, Windsor. I wish you were here at Westminster to stiffen my spine.

I must stand alone.

Gaunt’s description of events during that Parliament, for my personal perusal, was grim and graphic. Thud! Speaker de la Mare’s fist crashed down against the polished wood. Thud! And thud again, for every one of his demands. Where had the money gone from the last grant? The campaigns of the previous year had been costly failures. There would be no more money until grievances were remedied. He flashed a smile as smooth as new-churned butter. Now, if the King was willing to make concessions…It might be possible to reconsider.…

Oh, de la Mare had been well primed.

There must in future be a Council of Twelve—approved men! Approved by whom, by God? Men of rank and high reputation to discuss with the King all matters of business. There must be no more covens—an interesting choice of word that clawed at my rioting nerves—of ambitious, self-seeking money-grubbers to drag the King into ill-conceived policies against the good of the realm.

And those who were now in positions of authority with the King? What of them?

Corrupt influences, all of them, de la Mare raged, neither loyal nor profitable to the Kingdom. Self-serving bastards to a man! Were they not a flock of vicious vultures, dipping their talons into royal gold to make their own fortunes? They must be removed, stripped of their power and wealth, punished.

And when Parliament—when de la Mare—was satisfied with their dismissal? Why, then the Commons would consider the question of money for the war against France. Then and only then.

“Do they think they are kings or princes of the realm?” Gaunt stormed, impotent. “Where have they got their pride and arrogance? Do they not know how powerful I am?”

“You have no power when Parliament holds the purse strings,” I replied. The knot of fear in my belly grew tighter with every passing day, as we awaited the final outcome.

And there it was.

Latimer, Lyons, and Neville were singled out as friends of Gaunt. And the charge against them? De la Mare and his minions made a good legal job of it, ridiculously so. Not one, not a score, but more than sixty charges of corruption and abuse, usury and extortion. Of lining their pockets from trade and royal funds, falsification of records, embezzlement, and so on. I had a copy of the charges delivered to me, and read them with growing anxiety. De la Mare was out for blood; he would not be satisfied with anything less than complete destruction.

I tore the sheet in half as the motive behind the charges became as clear as a silver coin dropped into a dish of water. Guilt was not an issue here. The issue was their tight nucleus of control, a strong command over who had access to the King and who had not. Latimer and I might see our efforts as protection of an increasingly debilitated monarch; de la Mare saw us as a blight that must be exorcised by fire and blood. What did it matter that Latimer was the hero of the nation, who had excelled on the field of Crécy? What did it matter that he ran Edward’s household with superb efficiency? Latimer and his associates were creatures of Gaunt. De la Mare was delirious with power and would have his way. Gaunt was helpless.

Throughout the whole of this vicious attack on his ministers, Edward was ignorant.

For what was I doing?

Trying to keep the disaster from disturbing Edward, whose fragility of mind increased daily. And I would have managed it too, having sworn all around him to secrecy, except for a damned busybody of a chamber knight, a friend of Latimer and Lyons, who begged for Edward’s intercession.

I cursed him for it, but the damage was done.

After that there was no keeping secrets.

“They’ll not do it, Edward,” I assured him.

Dismissal. Imprisonment. Even execution for Latimer and Neville had been proposed.

“How can we tell?” Edward clawed at his robe, tearing at the fur so that it parted beneath his frenzied fingers. If he had been able to stride about the chamber, he would have done so. If he had been strong enough to travel to Westminster, he would have been there, facing de la Mare. Instead, tears at his own weakness made tracks down his face.

“This attack is not against you!” I tried. “They will not harm you. You are the King. They are loyal to you.”

“Then why do they refuse me money? They will bring me to my knees.” He would not be soothed.

“Gaunt has it in hand.” I tried to persuade him to take a sip of ale, but he pushed my hand away.

“It is not right that my ministers be attacked by Parliament.…” Did he realize that I too was not invulnerable against attack? I don’t think he did. His mind, besieged by all manner of evils, could not see the full scope of what de la Mare was planning. I enfolded Edward’s icy hand, warming it between both of mine. “I want to see the Prince…” he announced, snatching his hand away.

“He is not well enough to come to you.”

“I need to listen to his advice.” He was determined, struggling to his feet. I sighed. “I want to go today, Alice.…”

“Then you shall.…”

I could not stop him, so I would make it as easy as I could, arranging everything for Edward’s comfort for a journey to Kennington. I did not go with him: I would not be welcome there, and it would do no good to add to Edward’s distress by creating some cataclysmic explosion of emotion between myself and Joan. I prayed that the Prince would be able to give his father the comfort that I could not.

And so I made my own preparations. No longer could I delude myself that Latimer, Lyons, and Neville would escape without penalty. And when they fell…

So far my name had not been voiced in de la Mare’s persecutions. I had remained unremarked, but that would not last; I saw retribution approaching. I had myself rowed up the Thames to Pallenswick—thereby removing myself from Westminster and from any of the royal palaces. Discretion might be good policy. What effect would it have on Edward’s failing intellect and body if the one firm center of his life was gone? For once, the prospect of Pallenswick, the most beloved of all my manors, and reunion with my daughters, did not fill me with joy. Rather a black cloud of de la Mare’s making settled over my head.

Storm clouds. Storm crows.

The words came back to me, Windsor at his most trenchant. The presentiments of doom were gathering.

I shivered with fear as the days passed, heavy with portent. Even though I was isolated from the Court, could I not see the future danger, its teeth bared like a rogue alaunt? I needed no recourse to a fortune-teller, or to my physician, who had something of a reputation for the reading of signs. I could read them for myself while sitting watchful at Pallenswick, every nerve strained. Braveheart slept at my feet, unconcerned, lost in a dream of coneys and mice. The blade Windsor had given me lay forgotten in a coffer upstairs. The threat to me came not from an assassin’s dagger but from the heavy fist of the law.

The three royal ministers were dealt summary justice, their offices and possessions stripped from them. They were confined to prison, but the demands for execution died. Not even de la Mare could make the charge of treason stick. There was no treachery in these men to endanger King or state, unless acquiring a purseful of gold was treason. And if it was, then every man in government employ was guilty. But imprisonment was considered a just punishment. This was the price Latimer and Neville and Lyons paid for their association with John of Gaunt and Alice Perrers!

Holy Virgin! Would I be next? Gaunt, a royal son, would be safe, but the royal Concubine would be a worthy target. I too might end my days in a prison cell.

My mind leaped to Ireland, as it often did in those days.

Did Windsor know of my plight? It gave me some foolish comfort to think of him riding to my rescue. But of course he would not, and he was too far away to stretch out a hand to me. I shut out the image of his arms protecting me, his strength resisting any attack. It was too painful to imagine when I had no weapon that I might use. I had given Edward all I could—my youth, my body, my children. My unquestioning allegiance. Now I was truly alone.

And then, as expected, the charges against me arrived, ominously red-sealed. I had to sit, my legs suddenly too weak to hold me upright, as I read de la Mare’s accusations, a pain hammering at my temples as I absorbed the horror of it. What had they concocted to make my freedom untenable?

Ah…! As I read the first charge, the pain lessened. My breathing steadied. Predictable, nothing outrageous to shock me. I could answer this. I could state my defense. This was not so very terrible after all.…

She has seized three thousand pounds a year from the royal purse!

From where had they conjured that sum? Any monies I had taken were gifts from Edward. I had stolen nothing. It was his right to give gifts where he chose, and when I had borrowed to purchase some manor or feudal rights, it had never been without Edward’s consent. Except for the purchase of the manors of Hitchin and Plumpton End that very year, when Edward’s mind had slipped into some distant territory. And the borrowed sums had been paid back. For the most part, anyway…And if I had not repaid them through some oversight—well, I defied Parliament to find me guilty of fraud or embezzlement in that quarter.

She has seized Queen Philippa’s jewels. She wears them. She has no shame in proclaiming her immorality with the King.

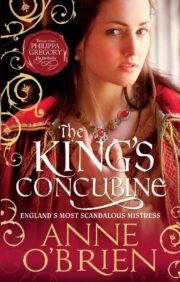

"The King’s Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.