“I can find out for you,” I suggested.

“Then do so. Why stand there wasting time?”

Once, four years ago, he had marched back to finish a conversation, apologizing for his rude manner. Now he stood and waited as if I might approach him. I did not. A neat little stalemate of our joint making.

“I do not answer to your beck and call, Sir William.” My reply echoed in the vast space.

Windsor bowed low, the gesture dripping with malice. “Sweet Alice, sweeter than ever. Will you be there when Edward tears my morals to shreds and damns my actions to hell and back?”

“Wouldn’t miss it for the world.”

“And will you speak out for me?”

“I will not. But neither will I condemn you until I’ve heard the evidence.”

“So you are not my enemy?”

“Did I ever say I was?”

A hard crack of a laugh was his only reply. At least I had made him laugh. He ran up the stairs, every action speaking of annoyance but with perhaps a lessening of the anger. Until at the head of the stair he halted and looked down to where I still stood below.

“Were you deliberately waiting for me?”

“Certainly not!”

The bow, the flourish of his cap, suggested that he did not believe me for a moment. I watched him disappear through the archway.

What now? I was not satisfied, not content to leave matters as they were. Never had I felt this need to be close to a man of the Court. Yes—through necessity, through courting their regard, through a need to win their support in a bid to protect Edward. But this? Windsor’s friendship—his regard—would bring me no good. And yet still I wanted it.

I considered as the distant sound of his boot heels died away. I did trust him more than I trusted Gaunt. And then I pushed him aside, unable to make sense of my troubled thoughts. Time would tell. And I would be there when Edward dissected his morals and his character. And no, I would not condemn him until I had heard his excuses.

Windsor’s presence continued to nibble at my consciousness. Nibble? Snap, rather. Like a kitchen cat pouncing on a well-fed and unwary rat.

Edward ordered Windsor to present himself one hour before noon on the following day, with no prompting from me. The King was lucid, furious. It was, I thought, very much a repetition of his interview with Lionel, without the close redeeming relationship of father to son. In the end Edward had forgiven Lionel. Here there was no softness, accusation following on accusation. Edward was angry and seethingly forthright: There was no impediment to his memory or his powers of speech that day.

Windsor proved to be equally uninhibited beneath the gloss of respect.

As I had intended, I sat beside Edward, fascinated at the play of will between the two men, impressed by Edward’s grasp of events, anxious that Windsor would not overstep the mark. Why was I anxious? Why should I care? I did not know. But I did.

Edward’s litany of crimes against his governor of Ireland rolled on and on.

“Bloody mismanagement…inglorious culpability…disgraceful self-interest…appalling fiscal double-dealing.”

Windsor withstood it all with a dour expression, feet planted, arms at his sides. I did not think his features had relaxed for one minute since his arrival the previous day.

Was he guilty? Despite his callous acceptance of my initial accusation, I had no idea. He argued his case with superb ease, not once hesitating. Yes, he had taxed heavily. Yes, he had used the law to support English power. Yes, he had empowered the Anglo-Irish at the expense of the native Irish—to do otherwise would have been political suicide. Was not the revenue needed to finance English troops to force the Irish rebels to keep their heads down? If that amounted to extortion and discreditable taxation, then he would accept it. In Ireland it was called achieving peace. And he would defy anyone to instigate peace in that godforsaken tribal, war-torn province by any other means than threats and bribery.

Edward was not impressed. “And the royal grant made for such purposes?”

“A grant I thank you for, Sire.” At least Windsor tried to be conciliatory. “But that was spent long ago. I am now on my own and have to take what measures I can.”

“I don’t like your methods, and I don’t like the rumble of dissatisfaction I hear.”

“When is there not dissatisfaction, Sire?”

“You are very voluble in defense of your innocence.”

How would he answer that? I waited, my heart thudding against my ribs.

His eyes never flinched from Edward’s face. “I would never claim innocence, Sire. A good politician can’t afford to be naive. Pragmatism is a far more valuable commodity, as you yourself will be aware. And who knows what’s happening while my back is turned?”

“They don’t want you back,” Edward accused.

Windsor shook his head, in no manner discomfited. “Of course they don’t. They want someone without experience, to mold and turn to their own will. I am not popular, but I hold to English policy as best I can with the tools I have. A weaker man would have the Irish lords singing his praises and licking the toes of his boots, all while they are sliding Irish gold into their own pockets.”

“They want me to send the young Earl of March,” Edward announced. “At least I know he’s honest.”

“I rest my case, Sire. Doubtless an able youth, but with neither experience nor years to his advantage…” Windsor left the thought hanging, his opinion clear.

“He is husband to my granddaughter!”

Edward was tiring. He might wish to champion the cause of young Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, wed to his granddaughter Philippa, but I could see the tension beginning to build in him, wave upon wave, as weakness crept over his mind and body. It was time to end this before his inevitable humiliation, I decided. Time to end it for Windsor too. I leaned across with a hand on Edward’s sleeve.

“How old is the young Earl, my lord?” I murmured.

“I think…” A frightening vagueness clouded his eyes.

“I doubt he has more than twenty-one years under his belt.” I knew he hadn’t.

“But he is my granddaughter’s husband.…” Edward clung to the single fact of which he was certain in the terrible mist that engulfed his mind, his voice growing harsh, querulous.

“And one day he will serve you well with utmost loyalty,” I agreed. “But it is an appallingly difficult province for so young a man.”

Edward looked at me. “Do you think?”

“There may be much in what Sir William says.…”

“No!” he huffed, but with agonizing uncertainty.

I had planted the seed. I looked at Windsor, willing him to a mood of diplomacy, and for the first time in the audience he returned my gaze. Then he bowed to Edward.

“Do I return to Ireland, Sire? To continue your work to hold the province? Until the Earl of March is fit to assume the role?”

It was impeccably done.

“I’ll consider your guilt first. Until then you’ll stay here under my eye.”

It was not an out-and-out refusal, but I doubted Windsor accepted it in that light. He bowed again and stalked out. I might as well not have been there.

“Come,” I said to Edward, helping him from his chair. “You will rest. Then we will talk of it—and you will come to a wise decision—as you always do.”

“Yes.” He leaned heavily on my arm, almost beyond speech. “We will talk of it.…”

So Windsor, against his wishes, was restored to the complex round of Court life, where all was seen and gossiped about, and it was increasingly difficult to keep Edward’s piteous decline from public gaze. For the first week I saw nothing of Windsor. Edward languished and Windsor kept his head down. No decision was made about the future of Ireland. How did Windsor spend his time? When last at Court he had sought me out. Now he did not. When Edward was strong enough to dine in public with a good semblance of normality, Windsor was not present. After some discreet questioning I discovered that he visited with the Prince at Kennington.

I wished him well of that visit. I thought there would be little satisfaction for him.

And then he was back, prowling the length and breadth of one of Edward’s antechambers, a black scowl on his face, a number of scrolls tucked under his arm. At least the scowl lifted when he saw me emerge from the private apartments. He loped across as I closed the door at my back. He even managed to smile, though there was no lightness in him. His mood gave me an urge to shock him out of his self-engrossment—except that I could think of no way of doing it. Nor did I have the energy. Edward had been morose and demanding. If there had been other courtiers waiting in the antechamber, I might even have avoided Windsor’s harsh, brooding figure. As it was…

“The King has not decided?” he demanded without greeting.

“No.”

“Will he never make a decision?”

I sighed, a weary hopelessness settling on me. “In his own good time. But you know that. You must be patient, Sir William. Are you waiting for me?”

“Certainly not.” He flashed a wolfish grin as he deliberately repeated my previous denial.

Tit for tat! I laughed softly, some of my weariness dispelled. “What are you doing to pass the time?” We were close enough that I tapped my fingers against the documents.

“Buying property.”

“In Ireland?” I was surprised.

“In England. In Essex, primarily.” I was even more surprised, since his family estates were far to the north.

“Why?”

“Against hard times. Like you. For when we can no longer depend on royal patronage.”

He looked at me, as if weighing up a thought that had entered his head. Or perhaps it had been there for some time.

“What is it?” I asked, suspicious.

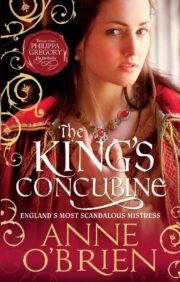

"The King’s Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.