“You should have told me you intended to return, Alice. I can give you only a few minutes, because…”

The burdens were hemming him in again. I saw the strain of holding his far-flung possessions together dragging at the muscles of his face. He looked beleaguered.

“We’re here to talk about your ministers, Sire,” Gaunt intervened gently.

“You know my feelings about that.…”

There was an irresolution about Edward that worried me. I touched his arm, drawing his eyes to my face.

“I have talked with your son, my lord. My advice is to do as he says.”

“My ministers have served me well.…”

“But Parliament will not give them the benefit of the doubt. You need money from Parliament whether you like it or not, Edward. How can you fight without their support? Dismiss your clerics, my lord. Now is not the time to be indecisive.”

I think I said no more and no less than Gaunt must have said already, but Edward listened to me.

“You think I should bow to Parliament’s will?” His mouth acquired a bitter downturn.

“Yes, Edward. I do. I think it would be good politics.”

So he did it.

And the men who came forward in the place of the unfortunate clerics proved to be the exact same coterie of men who had met with me in the circular room. All friends and associates of Gaunt, able men, ambitious men. Men who would serve Edward well and be loyal to Gaunt. Within the week the reorganization was complete. Carew became Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal. Scrope took on the burden of Treasurer. Thorp became the new Chancellor. William Latimer was honored with the position of royal Chamberlain, while Neville of Raby replaced him as Steward to the royal household. Thus a Court clique to close tightly around Edward and cushion him against the world that he found increasingly difficult to recognize.

I watched them bow before the King. Gaunt had it right: They were his men and would be bound to him, and since it was my influence that brought them to the forefront, they would be loyal to me also. Not one of them would dare oppose me, giving me friends at Court who would not neglect my interests.

So I took my first overt step into government circles.

“You must not worry, my lord.” I raised one of Edward’s hands to my lips. “They will serve you well.” The days when his palms were calloused from rein and sword were long gone. The strain in him, his lack of vision for the future, were pitiable. He was like an aging stag, still leader of the herd but with the weight of years beginning to dim the fire in his eye. Soon the hounds would be baying to drink his blood. Perhaps they already were.

“It is good that you are back,” he said. “Have you brought the infant?”

“No. She is with her nurse. But I will. You will see her.”

I accompanied him to the mews to inspect a new pair of merlins just taken into training, relieved to see him enjoy the moment as he handled the birds. Edward must not worry. But I would. I would do all I could to keep the dangers at bay.

Gaunt, I presumed, was satisfied with the outcome. He made no genuflection in my direction, but I felt the shackles that bound us together drawing tighter: We were undoubtedly in league, although whether I had sold my soul to Gaunt or he had sold his to me was open to debate. This was a marriage of convenience, and could be annulled if either saw fit. We were too wary of each other to be easy bedfellows, but for better or worse, in this political manipulation we were hand in glove.

The result of our conspiracy was immediate and inspiring. Edward addressed Parliament with all his old fire and won their approval, and the money was forthcoming. England could go to war again, whilst I smugly castigated the far-distant William de Windsor. Look to your enemies, he had warned me. He had been wrong. I had friends at Court now. Perhaps I should write to tell him. I consigned his dagger to a coffer.

“I don’t need you!” I informed an entirely unimpressed Braveheart, who had curled up on the hem of my gown.

And if I needed confirmation of the rise of my bright star in the heavens of Court politics, that was immediate too. When gifts were exchanged between the royal Plantagenets, as was habitual at Easter, the sense of Gaunt’s obligation to me must have struck him like a blow to the gut, for he was astonishingly and unexpectedly generous.

He proffered an object wrapped in silk.

I took it, unwrapped it.

Holy Virgin!

It was an exceptional object, a hanap such as I had never seen—a bejeweled drinking vessel, fashioned in silver and gleaming beryls, fit for a king.

Oh, I read Gaunt well. He had a need to keep my allegiance. My voice in his father’s ear was worth every ounce of silver, every one of the jewels set in the hanap, a gift to buy my favors if ever there was one. And why was it so very necessary for this Plantagenet prince to have a royal mistress on his side? Because, as every man in the land knew, of the uneasy state of the succession. Because with the rumors flying out of Gascony of the Prince’s health, no one would wager against the Prince dying before his father, and then the crown would pass to the Prince’s son Richard—a child of four years. A state did not thrive with its ruler not yet out of his minority.

Did Gaunt see the crown of England falling into his own lap? Children’s lives were vulnerable. Richard’s elder brother was already dead in Gascony. Richard might not live.

But Gaunt was not as close to the succession as he might like to be, for would not Lionel’s issue stand before him? Lionel, who had died so tragically in Italy, had produced a daughter by his first marriage. This child, Philippa, who was wed to Edmund Mortimer, the young Earl of March, was now mother to a daughter. If that young couple proved sufficiently fertile to produce a large family, a Mortimer son would take precedence over any offspring of Gaunt.

Not something to Gaunt’s liking, I judged. There was no love lost between him and the Earl of March.

My thoughts wove back and forth as I inspected the splendid cup, as any tapestry maker would create a picture of the whole. It was all too far in the future for speculation, but without doubt Gaunt had much to play for in this complex picture created in my mind. For who would be a better king within the next decade? The child Richard? A Mortimer son as yet unborn? Or Gaunt in his full strength?

And just supposing the situation was solved and Richard lived? Still all would not be lost for Gaunt. A governor would be needed for the young Richard, and it was no secret who would be the obvious choice to educate and protect and direct the young King. Gaunt, of course. Gaunt would be in control. And he might still see the Crown as a not impossible prospect for his own son, young Henry Bolingbroke. And what better than to have as an ally the King’s Concubine, who had the ear of the ailing King. Gaunt saw me as a useful arrow in his quiver in ensuring that the succession fell into the best hands, for nothing would persuade me that he did not have some scheme in mind. He was not a man to take second place, even to his brother, the dying heir, however deep his affection for him might be.

Was this treason on Gaunt’s part? Of course it was.

I smiled, in no manner seduced by the quality of the gift, understanding the motives of the giver perfectly.

“Thank you, my lord.” I curtsied. I would accept the gift, but my loyalty would remain true to Edward.

“It is my pleasure, Mistress Perrers.”

Gaunt too smiled, sly as a fox.

I was not without regrets in all this realigning of alliances and royal ministers. Wykeham, the man who trod the line between friend and enemy, was the one victim in the political maneuvering whom Edward truly mourned, and so did I. I doubted a more honest Chancellor ever existed, but Wykeham was swept away in the anticlerical hysteria. It was impossible to save him.

Edward’s departure from his minister was formal. Mine was not. He was packing his possessions, his beloved books and plans for even more buildings that would never now see the light of day. Standing at the open door, I watched him fold and place everything with meticulous neatness. William de Wykeham, Chancellor no longer. He was the closest to a friend, even if an unnervingly judgmental one, that I had. I did not call Windsor a friend. I was not sure what Windsor was to me.

He did not even turn his head. “If you’ve come to gloat, don’t bother.”

“I have not come to gloat.” Wykeham continued wrapping a bundle of pens in a roll of cloth. “I have come to say farewell.”

“You’ve said it. Now you can go.”

He was hurt, and with every justification. I had stood at Edward’s side and listened to the empty phrases of regret and well-wishing. It had been necessary, and Edward felt the hurt just as keenly as Wykeham, but the man deserved more. I walked ’round the room to force him to face me. He foiled me by picking up and rummaging in a saddlebag.

“Winchester will see more of you,” I remarked, holding out a missal to him.

He snatched it from me. “I will apply my talents where they are appreciated.”

“I’m sorry.”

Now he looked at me. And I saw the pain of betrayal in his doleful eyes. “I never thought you would be the instrument of my dismissal. I thought you valued loyalty and friendship.” He sneered. “You have so many friends, do you not? You can afford to be casual with them.” I felt the blood stain my cheeks. “How wrong a man can be when he doesn’t want to see the truth!”

“I don’t think I was the instrument,” I observed, keeping clear of sentiment. “Parliament wanted you gone. All of you.”

“For crimes none of us committed. For lack of ability—and with what proof? We’ve more experience than the whole job lot of Parliament put together!” He shrugged, placing two more books into the bag. “I didn’t hear you trying to persuade Edward to be loyal to old friends!”

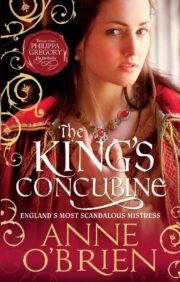

"The King’s Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.