“Nothing,” I replied, hands folded neatly in my lap. “Nothing that was not to puff up his own self-aggrandizement. The man speaks of no one but himself.” Not quite true, but close enough.

“Hmm.” Edward’s brow furrowed in familiar disquiet. He began to loose my hair from its neat braids, although I thought his mind was not on the pleasures of the flesh. Windsor had even infiltrated the royal bedchamber. Edward tugged persuasively against my hair. “What do you make of him?”

“I don’t like him.”

“Nor do I. Would he be honest in government, d’you think?”

“I doubt it.”

Edward grunted a laugh. “Well, that’s plain enough. Would he be loyal to me?”

“Yes, if it brought him money and power.” Which was as honest as I could be.

“You seem to have read the man in some depth in so short a time.” The frown was back, now turned on me.

“It wasn’t difficult.” I smiled disingenuously. “A more boastful man I have yet to meet. He thinks you will make use of him—send him back to Ireland.” The frown deepened, so I turned my head to plant a kiss on his hands where they were wound into my hair. “Will you use him?”

“I’m not sure. I think he’s got a chancy kick in his gallop.”

So did I, and perhaps not for the same reasons.

Wykeham, returned to Court on the occasion of the feast, was less than polite. Our steps fell into line after Mass the next morning. He had not officiated but stood toward the back of the small body of courtiers. I had noticed him when I had glanced over my shoulder to see whether Windsor was present. My lips curled in high-minded satisfaction as I noted that he was not. But Wykeham was there. And he had waited for me by design.

“I see Windsor has singled you out,” he stated without preamble.

“It is good to see you again too, Wykeham,” I remarked. “Perhaps you are even pleased to see me?” Wykeham had achieved a remarkable elevation: Bishop of Winchester and Lord High Chancellor of England—high indeed for a man whose main interest was the supreme angle of a buttress to prevent a castle wall from collapsing on hapless soldiery. For his impertinence, it pleased me to needle him a little. “Or are you now too important to take note of one such as I?”

“It’s always an experience, mistress, to converse with you.” Wykeham refused to acknowledge my pert jibe. “Why do you think Windsor is sniffing ’round your heels?”

“Is he?” I sighed. “I have no idea.”

“I’ll tell you why. To get the ear of the King.”

“Then he won’t succeed. I’m no friend of Windsor’s. Do you consider me gullible, to be flattered and taken in by every ambitious office seeker?”

I stared at him, hoping for an apology. There was no apology from the King’s new Chancellor.

“I consider that you lack experience when dealing with a man of his mettle,” Wykeham announced, pausing between every word, the echoing thud of his steps providing counterpoint. “He’s proud, ruthless, avaricious, ambitious, opportunistic, and quite without principle.”

“You omitted talented.” I smiled at his glower. “And who isn’t guilty of any one of those entirely useful commodities at this Court, my lord?”

Wykeham scowled.

“Even you, sir. Pride and ambition seem to me to be fair game for a priest newly appointed Lord Chancellor.”

With a curtsy and a swish of my skirts, I left him standing at the door to the Queen’s chambers.

Philippa pursed her lips. “I’d not trust him. I wonder why Lionel finds him such good company.”

“I have no idea, my lady,” I replied.

“You did not find him entertaining at the feast?”

I took a steadying breath. Had our conversation gone unnoticed in any quarter?

“No. I can’t say that I did, my lady.”

Good company? Entertaining? He had been positively sinister, the manner in which he had poked at my anxieties, undermining my carefully constructed self-possession. Within twenty-four hours of our meeting, it was as clear as the bell on Edward’s clock: No one liked or trusted William de Windsor.

The question I was driven to ask myself: Did I?

For William de Windsor had an unpleasant habit of stepping into my thoughts and trampling any attempt I made to dismiss him.

I was present, in attendance on the Queen, when Edward summoned Lionel, flanked by Windsor, to a council of war, to hammer out the thorny matter of Irish administration. Philippa rarely concerned herself with matters of business or politics these days, but her concern for Lionel, and her fear for her husband’s temper, brought her to the council table. I was not displeased. How could I have found a reason for being there, to watch Windsor in action, if the Queen had not made it easy for me? I wanted to hear Windsor’s excuses for his own involvement in the Irish problems. I wanted to see him squirm.

The King did not use his words with care or reticence.

“God’s Bones, Clarence! I thought a son of mine would have more backbone.”

“Do you have any idea what it is like?” Lionel challenged with what I considered to be an unfortunate degree of heat. “The native Irish are untamable. The English born in Ireland are loyal to the English throne only when it suits them. The only lot you can rely on are the English born in England, and they, to a man, are naught but a rascally band of brigands.”

“So you hold the balance between them! Do you leave the province in turmoil and make a run for it, leaving them to wallow in their own blood?”

“I feared for my life.” Lionel’s pretty face was unattractively surly.

“I expect you to communicate with them, not ban them from your august presence! I expect you to get them to trust you! And don’t make excuses for him,” he snapped at Philippa, who had placed a hand on Edward’s arm, as if it were possible to stem the tirade. “Your son is a coward. You’re lily-livered, Lionel.” As his ire grew, Edward became colder, the skin taut and white around his lips, his eyes pale with ice. “In my day…”

I slid my gaze to William de Windsor. His attention appeared to be focused on the carved wainscoting behind the King’s right shoulder. How would leaves and tendrils deserve such concentration? Then his eyes moved to mine…but I could not read them. Anger or caprice or even a cool distancing—impossible to say, but an unexpected self-consciousness came to me. I looked away, down at my clasped hands.

“As for the army.” The King brought his fist down hard onto the wood, causing the metal cups to ring and jump. “I hear there’s rape and pillage committed by my forces in my name. I hear they’re forced to loot to maintain themselves. What happened to the revenues I directed toward Ireland? What happened to the taxes? Whose pockets did they disappear into…?” Without warning, Edward swung ’round in his chair to change his target. “I hear no good of you, Windsor.”

And what would William de Windsor have to say about that? I was holding my breath. Did I want him to emerge victorious from this bout, or be buried under the justice of Edward’s recriminations? I did not know.

Windsor was entirely undismayed, his harsh features an essay in composure. His voice held neither slick apology nor Lionel’s aggression. I should not have been surprised.

“I admit the problems in the province,” he replied. “I carry out orders, Sire, to the best of my ability. I was paid what was due to me. My lord of Clarence is King’s Lieutenant; his is the authority. I am merely a loyal servant of the Crown.”

It was a formidable statement of innocence.

“You’re quick to slough off any blame, Windsor,” Lionel snarled.

“I suppose you take no action on your own authority,” Edward demanded of Windsor, waving his son to silence.

“No, Sire,” Windsor responded, undisturbed, outwardly at least, by either the King’s contempt or Lionel’s fury. Against my better judgment, he won my acclaim.

“You think Ireland’s a lost cause?”

Windsor thought for a long moment, as if it were a new idea, studying his hands that were placed flat, palms down, on the council table before him. If he said yes, he would displease the King; if no, then Lionel’s excuses would be undermined by one of his own officers. Which way would he jump? Windsor raised his eyes and cast his dice.

“No, Sire. I do not.”

He did not even look toward Lionel. He had known what he would say from the outset. He had his future entirely planned out, with or without Lionel. Had he not admitted to being ambitious, thoroughly self-interested? He might have omitted unscrupulous, but I recognized it.

“Ireland is dangerous, unpredictable,” Windsor stated. “It’s on the edge of rebellion. But I think it can be remedied. It just needs careful handling.”

“And you could do it.” The King made no effort to hide his distaste.

“Yes.”

“At a cost, I suppose.”

“As you say, Sire,” Windsor concurred. “With enough power and wealth behind me, I’ll whip Ireland into shape.”

“I’ll consider…” Edward fell into an abstraction. His fingers began to tap on the table’s edge. His deliberation stretched out in an endless, uncomfortable silence, and his fingers stilled. His gaze, turned toward the window with its colored glazing, seemed to lose its focus. Those around the table began to stir in their seats. Still the King made no pronouncement. I became aware of the slide of unnerved glances from one man to another around the table as Edward sat motionless, lost in some inner thought.

“Edward!” Philippa demanded his attention. She placed a hand on his arm. And then apparently apropos of nothing, she added, “Edward! We must find Lionel a new wife.”

The King blinked as if drawing back from the edge of some dark precipice.

“Yes, yes. So we must. I have it in mind.” He was uncommonly brusque, although I knew that Lionel’s remarriage after the death of his young wife three years ago now was a matter of policy. A new royal wife would mean the prospect of a new alliance. “But first this other matter…” Edward frowned, hesitated.

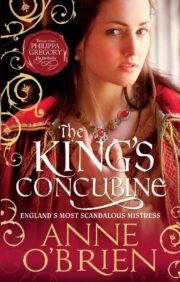

"The King’s Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.