I did not think it mattered what I said, given the continuing obscenities from the two lads struggling to manhandle a side of venison onto a spit. I had already been judged. I would be given the lowliest of tasks. I would be a butt of jokes and innuendo.

“Come on, girl! I’ve never yet met a woman with nothing to say for herself.”

So I would. I would state my case. I would not hide. So far, I had been moved about like the bolt of cloth he had called me, but if this was to be my future, I would not sink into invisibility. With Signora Damiata I had controlled my manner, because to do otherwise would have called down retribution. Here I knew instinctively that I must stand up for myself as I had never done before.

“I can do that, Master Humphrey. And that.” I pointed at the washing and scouring going on in a tub of water. “I can do that.” A small lad was piling logs on the fire.

“So could an imbecile.” The cook aimed a kick at the lad at the fire, who grinned back. “No skills, then.”

“I can make bread. I can kill those.” Chickens clucked unsuspectingly in an osier basket by the hearth. “I can do that.” I pointed to an older man who was gutting a fish, scooping the innards into a basin with the flat of his hand. “I can make a tincture to cure a cough. And I can make a…”

“My, my. What an addition to my kitchen.” Master Humphrey gripped his belt and made a mocking little bow. He did not believe half of what I said.

“I can keep an inventory of your foodstuffs.” I was not going to shut up unless he ordered me to. “I can tally your books and accounts.”

“A miracle, by the Holy Virgin.” The mockery went up by a notch. “What is such a gifted mistress of all crafts doing in my kitchen?” The laughter at my expense expanded too. “Let’s start with this for now.”

I was put to work raking the hot ashes from the ovens and scouring the fat-encrusted baking trays. No different from the Abbey or the Perrers household at all.

But it was different, and I relished it. Here was life at its coarsest and most vivid, not a mean existence ruled by silence and obedience with every breath I took. This was no living death. Not that I enjoyed the work—it was hard and relentless and punishing under the eyes of Master Humphrey and Sir Joscelyn—but here was no dour disapproval or use of a switch if I sullied Saint Benedict rule, or caught Damiata’s caustic eye. Everyone had something to say about every event or rumor that touched on Master Humphrey’s kitchen. I swear he could discuss the state of the realm as well as any great lord, while slitting the gizzard of a peacock. It was a different world. I was now the owner of a straw pallet in a cramped attic room with two of the maids who strained the milk and made the huge rounds of cheese in the dairy. I was given a blanket, a new shift and kirtle—new to me, at any event—a length of cloth to wrap ’round my hair, and a pair of rough shoes.

Better than a lay sister at St. Mary’s? By the Virgin it was!

I listened as I toiled. The scullions gossiped from morn till night, covering the whole range of the royal family, and I lapped it up. Countess Joan, who had married her prince, was little better than a whore. The Queen was ill, the King protective. The King was well past the days of his much-lauded victory on the battlefield of Crécy against the bloody French, but still he was a man to be admired. Whilst Isabella! A madam, refusing every sensible marriage put to her! The King should have taken a whip to her sides! Gascony and Aquitaine, our possessions across the channel, were in revolt. Ireland was simmering like a pot of soup. Now, the buildings of the man Wykeham. At Westminster, water directed to the kitchens ran direct from a spigot into a bowl! May it come to Havering soon, pray God.

Meanwhile I was sent to haul water from the well twenty times a day. Master Humphrey had no need for me to read or tally. I swept and scoured and chopped, burned my hands, singed my hair, and emptied chamber pots. I lifted and carried and swept up. And I worked even harder to keep the lascivious scullions and pot boys at a distance. I learned fast. By God, I did!

Sim was the biggest lout of them all, with his fair hair and leering smile.

I did not need any warning. I had seen Sim’s version of romantic seduction when he trapped one of the serving wenches against the door of the wood store. It had not been enjoyment on her face as he had grunted and labored, his hose around his ankles. I did not want his greasy hands, or any other part of his body, on me. The stamp of a foot on an unprotected instep, a sharp elbow to a gut kept the human vermin at bay for the most part. Unfortunately it was easy for Sim and his slimy crowd to stalk me in the pantry or the cellar. His arm clipped my waist once, and did so a dozen times within the first week.

“How about a kiss, Alice?” he wheedled, his foul breath hot against my neck.

I punched his chest with my fist, and not lightly. “You’ll get no kiss from me!”

“Who else will kiss you?” he demanded, followed by the usual chorus of appreciation from the crude, grinning mouths.

“Not you!”

“You’re an ugly bitch, but you’re better than a beef carcass.”

“You’re not, slimy Sim. I’d sooner kiss a carp from the pond. Now, back off—and take your gargoyles with you.” I had discovered a talent for wordplay and a sharp tongue, and used them indiscriminately, along with my elbows. Self-preservation was a wonderful spur.

“You’ll not get better than me.” He ground his groin, fierce with arousal, against my hip.

I gave up on the banter. My knee slamming against his privates loosened his hold well enough. “Keep your hands to yourself! Or I’ll take Master Humphrey’s boning knife to your balls! We’ll roast them for supper with garlic and rosemary!”

I was not unhappy. But I was sorry not to be pretty. And my talents were not used. How much skill did it take to empty the chamber pots onto the midden?

Then all was danger, without warning. Two weeks of the whirlwind of kitchen life at Havering had lulled me into carelessness. And on that day I had been taken up with the noxious task of scrubbing down the chopping block where the joints of meat were dismembered.

“And when you’ve done that, fetch a basket of scallions from the storeroom—and see if you can find some sage in the garden. Can you recognize it?” Master Humphrey shouted after me, still leaning toward the scathing.

“Yes, Master Humphrey.” Any fool can recognize sage. I wrung out the cloth, relieved to escape the heat and the sickening stench of fresh blood.

“And bring some chives while you’re at it, girl!”

I was barely out of the door when my wrist was seized in a hard grip and I was almost jolted off my feet.

“What…?”

And into the loathsome arms of Sim.

“Well, if it isn’t Mistress Alice with her good opinion of herself!”

I raised my hand to cuff his ear but he ducked and held on. This was just Sim trying to make trouble, since I had deterred him from lifting my skirts with the point of a knife, and the red punctures still stood proud on his hand.

“Get off me, you oaf!”

Sim thrust me back against the wall and I felt the familiar routine of his knee pushing between my legs.

“I’d have you gelded if I had my way!” I bit his hand.

Sim was far stronger than I. He laughed and wrenched the neck of my tunic. I felt the shoulder of my shift tear, and then Queen Philippa’s rosary, the precious gift that I had worn out of sight around my neck, slithered under my shift to the floor. I squirmed, escaped, and pounced. But not fast enough. Sim snatched it up.

“Well, well!” He held it up above my head.

“Give it back!”

“Let me fuck you and I will.”

“Not in this lifetime…” My whole concentration was on my beads.

So was Sim’s. He eyed the lovely strand where it swung in the light, and I saw knowledge creep into his eyes. “Now, this is worth a pretty penny, if I don’t mistake.…”

He would keep it for himself. But perhaps the value was too great even for Sim to risk.…I snatched at it but he was running, dragging me with him. At that moment as I almost tripped and fell, I knew. He would make trouble for me. Here was danger.

“What’s this?” Master Humphrey looked up at the rumpus.

“We’ve a thief here, Master Humphrey!” Sim’s eyes gleamed with malice.

“I know you are, my lad. Didn’t I see you pick up a hunk of cheese and stuff it into your big gob not an hour ago?”

“This’s more serious than cheese, Master Humphrey.” Sim’s grin at me was an essay in slyness.

In an instant we were surrounded. “Robber! Pick-purse! Thief!” came a chorus from idle scullions and mischief-making pot boys.

“I’m no thief!” I kicked Sim on the shin. “Let go of me!”

“Bugger it, wench!” His hold tightened. “Told you she wasn’t to be trusted.” He addressed the room at large. “Too high an opinion of herself by half! She’s a thief!” And he raised one hand above his head, Philippa’s gift gripped between his filthy fingers. The rosary glittered, its value evident to all. Rage shook me. How dared he! How dared he take what was mine!

“Thief!”

“I am not!”

“Where did you get it?”

“She came from a convent.” One voice was raised on my behalf.

“I wager she owned nothing as fine as this, even in a convent.”

“Fetch Sir Joscelyn!” ordered Master Humphrey. “I’m too busy to deal with this.”

And then it all happened very quickly. Sir Joscelyn gave his judgment: “This belongs to Her Majesty.” No one questioned his decision. All eyes were turned on me, wide with disgust. “The Queen is ill, and you would steal from her!”

“She gave it to me.” I knew I was already pronounced guilty, but my instinct was to fight against the inevitable.

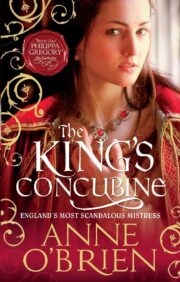

"The King’s Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.