I watch them from my chamber windows set high in the castle wall so that they are far below, walking to the river, like a painting of a knight and his lady in a romance. She is tall, almost as tall as he, and they walk together head to head. I wonder idly what they talk about with such animation, what makes her laugh and stop and put her hand to her throat, and then makes her take his arm to walk on. At this distance, from my high window, they are a handsome couple: well-matched. They are not far from each other in age, after all. She is eighteen and he is only thirty-one. They both have the York charm that is now turned fully on each other. She is golden-haired like his brother and he is dark as his handsome father. I see Richard take her hand and draw her a little closer as he whispers in her ear. She turns her head with a little laugh, she is a coquette as most beauties of eighteen are bound to be. They walk away from the court and people follow them, at a little distance so that they can imagine themselves to be alone.

The last time I saw the court walking behind the king and carefully judging their paces was when Edward was walking arm in arm with his new lover Elizabeth Shore, and Elizabeth his queen was in confinement. The moment she came out the Shore whore disappeared from court and was never seen again by us – I smile at the memory of the king’s bashful apologetic tenderness to his wife and her grey-eyed level gaze at him. Odd now for me to see the court taking slow strides once more; but this time it is my husband who is being given privacy, as he walks alone with his niece.

Why would they do that? I think idly, my forehead against the cold glass of the thick window. Why would the courtiers step back so courteously unless they think that she is to be his mistress? Unless they think that my husband is seducing his niece, on these evening strolls by the river, that he has forgotten everything he owes to his name, to his marriage vows, to the respect he owes to me as his wife, and the bereaved mother of his dead son.

Can it be that the court has seen so much more clearly than I that Richard has recovered from grief, recovered from heartbreak, can live again, can breathe again, can look about him and see the world again – and in this world sees a pretty girl who is all too ready to take his hand and listen to his words and laugh as if delighted at his speech? Does the court think that Richard is going to bed his brother’s daughter? Does it really think he is so far gone in wickedness to deflower his niece?

I approach this thought, whispering the words ‘deflower’ and ‘niece’, but I really cannot make myself care about this, any more than I can make myself care about the hunting trip tomorrow or the dishes for tonight’s dinner. Elizabeth’s virginity and Elizabeth’s happiness are alike of no interest to me at all. Everything seems as if it is happening a long way away, feels as if it is happening to someone else. I would not call myself unhappy, the word does not approach my state of mind; I would call myself dead to the world. I cannot find it in me to care whether Richard is seducing his niece or she is seducing him. I see, at any rate, that Elizabeth Woodville, having taken my son from me by a curse, will now take my husband from me by her daughter’s seduction. But I see that there is nothing I can do to stop this. She will do – as she always does – as she wishes. All I can do is lean my hot forehead against the cold glass and wish that I did not see this. Or anything. Anything at all.

The court is not solely devoted to the hypocrisy of flirting with the king and mourning with me. Richard spends every morning with his councillors, appointing commissioners to raise the shires if there is an invasion from Henry Tudor in Brittany, preparing the fleet to make war with Scotland, harrying French shipping in the narrow seas. He speaks to me of this work and sometimes I can advise him, having spent my childhood at Calais, and since it is my father’s policy of peace with the Scots and armed peace against the French that Richard follows.

He leaves for York in July to establish the Council of the North, the recognition that the North of England is a country in many ways quite different from the southern parts, and Richard is, and will always be, a good lord to them. Before he leaves he comes to my room and sends my ladies away. Elizabeth goes out with a backward smile at him and for once he does not notice. He takes a stool so that he is seated at my feet.

‘What is it?’ I ask without a great deal of interest.

‘I wanted to speak to you about your mother,’ he says.

I am surprised but nothing can catch my interest. I complete the sewing I have in my hands, pierce the needle through the embroidery silks, and put it to one side. ‘Yes?’

‘I think she can be released from our care,’ he says. ‘We won’t go back to Middleham—’

‘No, never,’ I say quickly.

‘And so we could close the place down. She could have her own house, we could pay her an allowance. We don’t need to keep a great castle to house her.’

‘You don’t think she might speak against us?’ Never am I going to refer to the question of our marriage. He can think me now, as I was then, utterly trusting. Now I cannot bring myself to care.

He shrugs. ‘We are King and Queen of England. There are laws against speaking against us. She knows that.’

‘And you don’t fear she will try to take her lands back?’

Again he smiles. ‘I am King of England, she is unlikely to win a case against me. And if she were to get some estates back into her own keeping, I can afford to lose them. You will have them back again when she dies.’

I nod. And anyway, now there is no-one to inherit from me.

‘I just wanted to make sure that you had no objection to her being freed. If you had a preference as to where she should live?’

I shrug. There were four of them at Middleham that winter, Margaret and her brother Teddy, my son Edward and her, my mother, their grandmother. How is it possible that death should have taken her grandson and not taken her? ‘I have lost a son,’ I say. ‘How can I care about a mother?’

He turns his head away, so that I cannot see his grimace of pain. ‘I know,’ he says. ‘The ways of God are mysterious to us.’

He rises to his feet and puts his hand out for me. I get up and stand beside him, smoothing the exquisite silk of my gown.

‘That’s a pretty colour,’ he says, noticing it for the first time. ‘Do you have more of that silk?’

‘I think so,’ I say, surprised. ‘They bought a bolt of it from France, I believe. Do you want a jacket made from it?’

‘It would suit our niece Elizabeth,’ he says lightly.

‘What?’

He smiles at my aghast face. ‘It would suit Elizabeth’s colouring, don’t you think?’

‘You want her to wear a matching gown to mine?’

‘Now and then – if you agree that the colour is good on her too.’

The ridiculous concept stirs me from my lethargy. ‘What are you thinking of? The whole court will think that she is your mistress if you dress her in silks as fine as mine. They will say worse. They will call her your whore. And they will call you a lecher.’

He nods, utterly unshocked by the hard words. ‘Just so.’

‘You want this? You want to shame her, and shame yourself, and dishonour me?’

He takes my hand. ‘Anne, my dearest Anne. We are king and queen now, we have to put aside private preferences. We have to remember we are constantly observed, our acts have meanings that people try to read. We have to put on a show.’

‘I don’t understand,’ I say flatly. ‘What are we showing?’

‘Is the girl not supposed to be betrothed?’

‘Yes, to Henry Tudor, you know as well as I do that he publicly declared himself last Christmas.’

‘And so who is the fool, when she is known to the world as my mistress?’

Slowly I understand. ‘Why, he is.’

‘And so all the people who would support this unknown Welshman, Margaret Beaufort’s Welsh-born boy, because he is betrothed to marry the Princess Elizabeth – the beloved daughter of England’s greatest king – think again. They say, if we rally for Tudor we are not putting the Princess of York on the throne. For the Princess of York is at her uncle’s court, admiring him, supporting him, an ornament to his reign as she was an ornament to her father’s reign.’

‘But some people will say she is little better than a whore. She will be shamed.’

He shrugs. ‘They said the same of her mother. We passed a law that said just that of her mother. And anyway, I would not have thought that would trouble you.’

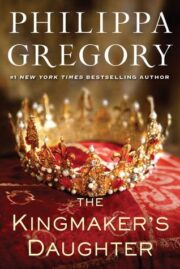

"The Kingmaker’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Kingmaker’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Kingmaker’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.