He is as white as a drowned man in the gloom, his eyes hollow in his face. All his debonair good looks are wiped away. He looks like a man at the very end of his tether. ‘What is it?’ I whisper.

‘My son,’ he says brokenly. ‘My son.’

My first thought is of my own son, my Edward. Pray to God that he is safe at Middleham Castle, sledging in the snow, listening to the mummers, tasting a mug of Christmas ale. Pray God he is well and strong, untouched by plague or poison.

‘Your son? Edward?’

‘My baby, Richard. My baby, my beloved: Richard.’

I put my hand to my mouth, and beneath my fingers I can feel my lips tremble. ‘Richard?’

Isabel’s motherless baby is cared for by his wet nurse, a woman who had raised both Margaret and Edward, whose milk had fed them as if she were their mother. There is no reason why Isabel’s third child should not thrive in her keeping. ‘Richard?’ I repeat. ‘Not Richard?’

‘He’s dead,’ George says. I can hardly hear his whisper. ‘He’s dead.’ He chokes on the word. ‘I just had a message from Warwick Castle. He’s dead. My boy, Isabel’s boy. He has gone to heaven to be with his mother, God bless his little soul.’

‘Amen,’ I whisper. I can feel a thickening in my throat, a burning in my eyes. I want to pitch down onto my bed and cry for a week for my sister and my little nephew and the hardness of this world, that one after another takes all the people that I love.

George fumbles for my hand, grips it tight. ‘They tell me that he died suddenly, unexpectedly,’ he says.

Despite my own grief, I step back, pulling my hand from his grasp. I don’t want to hear what he is going to say. ‘Unexpectedly?’

He nods. ‘He was thriving. Feeding well, gaining weight, starting to sleep through the night. I had Bessy Hodges as his wet nurse, I would never have left him if I had not thought he was doing well, for his own sake as well as his mother’s. But he was well, Anne. I would never have left them if I had any doubt.’

‘Babies can fail very suddenly,’ I say weakly. ‘You know that.’

‘They say he was well at bedtime and died before dawn,’ he says.

I shiver. ‘Babies can die in their sleep,’ I repeat. ‘God spare them.’

‘It’s true,’ he says. ‘But I have to know if he just fell asleep, if it is innocent. I am leaving for Warwick right now. I shall have the truth of this, and if I find that someone killed him, dripped poison into his little sleeping mouth, then I will take their life for it – whoever they are, however grand their position, however great their name, whoever they are married to. I swear it, Anne. I shall have vengeance on whoever killed my wife, especially if she killed my son too.’

He turns for the door and I grip his arm. ‘Write to me at once,’ I whisper. ‘Send me something, fruit or something with a note to tell me. Write it in such a way that I will understand but nobody else can know. Make sure that you tell me that Margaret is safe, and Edward.’

‘I will,’ he promises. ‘And if I see the need I will send you a warning.’

‘A warning?’ I don’t want to understand his meaning.

‘You are in danger too, and your son is in danger. There is no doubt in my mind that this is more than an attack on me and mine. This is not an attack solely on me, though it strikes me to the heart; this is an attack on the kingmaker’s daughters and his grandsons.’

At his naming this fear I find I am cold. I go as white as him, we are like two ghosts whispering together in the shadows of the chapel. ‘An attack on the kingmaker’s daughters?’ I repeat. ‘Why would anyone attack the kingmaker’s daughters?’ I ask, though I know the answer. ‘He has been gone six years this spring. His enemies have all forgotten.’

‘One enemy has not forgotten. She has two names written in blood on a piece of paper in her jewel box,’ he says. He does not need to name the ‘she’. ‘Did you know this?’

Miserably, I nod.

‘Do you know whose names they are?’

He waits for me to shake my head.

‘Written in blood it says: “Isabel and Anne”. Isabel is dead, I don’t doubt that she plans you will be next.’

I am shaking in my fear. ‘For vengeance?’ I whisper.

‘She wants revenge for the death of her father and her brother,’ he replies. ‘She has sworn herself to it. It is her only desire. Your father took her father and his son, she has taken Isabel and her son. I don’t doubt she will kill you and your son Edward.’

‘Come back soon,’ I say. ‘Come back to court, George. Don’t leave me here alone at her court.’

‘I swear it,’ he says. He kisses my hand and is gone.

‘I can’t go to court,’ I say flatly to Richard, as he stands before me, in rich dark velvet, ready to ride to Westminster where we are bidden for dinner. ‘I can’t go. I swear I cannot go.’

‘We agreed,’ he says quietly. ‘We agreed that until we knew the truth of the rumours that you would attend court, sit with the queen when invited, behave as if nothing has happened.’

‘Something has happened,’ I say. ‘You will have heard that the little baby Richard is dead?’

He nods.

‘He was thriving, he was born strong, and now he dies, only three months after his birth? Dies in his sleep with no cause?’

My husband turns to the fire and pushes a log into place with his booted foot. ‘Babies die,’ he says.

‘Richard, I think She killed him. I can’t go to court and sit in Her rooms and feel Her watching me, wondering what I know. I can’t go to dinner and eat the food from Her kitchen. I cannot bring myself to meet Her.’

‘Because you hate her?’ he asks. ‘My dearest brother’s wife and the mother of his children?’

‘Because I am afraid of Her,’ I say. ‘And perhaps you should be too, perhaps even he should be.’

LONDON, APRIL 1477

When I enter I am shocked at George’s appearance. He has grown even thinner during his absence, his face is lean and weary, he looks like a man who is undertaking work he can hardly bear to do. Richard glances up when I come in and holds out his hand to me. I stand beside his chair, handclasped.

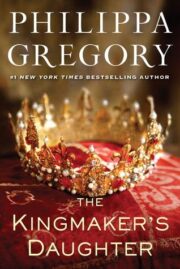

"The Kingmaker’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Kingmaker’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Kingmaker’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.