"Don't be idiotic, Teddy," said Vita sharply. "That's just the sort of frightful way rumours spread. It would upset Dick terribly to hear you say things like that. I hope you didn't suggest such a thing to Mr. Collins."

"Mr. Collins thought of it first," chimed in Micky. "He said you never knew what scientists were up to these days, and the Professor might have been looking for a site for a hush-hush research station up the Treesmill valley."

This conversation had the instant effect of pulling me together. I thought how Magnus would have loved it, played up to it, too, encouraged every exaggeration. I coughed loudly and went towards the kitchen, hearing Vita say Ssh… as I passed through the door. The boys looked up, their small faces taking on the expression of shy discomfort that children wear when suddenly confronted with what they fear to be an adult plunged in grief.

"Hullo," I said. "Had a good day?"

"Not bad," mumbled Teddy, turning red. "We went fishing."

"Catch anything?"

"A few whiting. Mom's cooking them now."

"Well, if you've any to spare, I'll stand in the queue, I had a cup of coffee and a sandwich in Fowey, and that's been my lot for the day." They must have expected me to stand with bowed head and shaking shoulders, for they cheered visibly when I attacked a large wasp on the window with the fly-swatter, saying "Got him!" with enormous relish as I squashed it flat. Later, when we were eating, I said to them, "I may be a bit tied up next week because they'll have to hold an inquest on Magnus, and there'll be various things to attend to, but I'll see to it that you go out with Tom in one of his boats from Fowey, engine or sailing, whichever you like best."

"Oh, thanks awfully," said Teddy, and Micky, realising that the subject of Magnus was no longer taboo, paused, his mouth full of whiting, and enquired brightly, "Will the Professor's life story be on TV tonight?"

"I shouldn't think so," I replied. "It's not as if he were a pop-singer or a politician."

"Bad luck," he said. "Still, we'd better watch just in case."

There was nothing, much to the disappointment of both boys, and secretly, I suspected, of Vita too, but to my own considerable relief. I knew the next few days would bring more than enough in the way of publicity, once the press got hold of the story, and so it proved. The telephone started ringing first thing the following morning, although it was Sunday, and either Vita or I spent most of the day answering it. Finally we left it off the hook and installed ourselves on the patio, where reporters, if they rang the front-door bell, would never find us. The next morning she took the boys into Par to do some shopping, leaving me to my mail, which I had not opened. The few letters I had were nothing to do with the disaster. Then I picked up the last of the small pile and saw, with a queer stab of the heart, that it was addressed to me in pencil, bore an Exeter postmark, and was in Magnus's handwriting. I tore it open.

'Dear Dick,' I read, 'I'm writing this in the train, and it will probably be illegible. If I find a post-box handy on Exeter station I'll drop it in. There is probably no need to write at all, and by the time you receive it on Saturday morning we shall have had, I trust, an uproarious evening together with many more to come, but I write as a safety-measure, in case I pass out in the carriage from sheer exuberance of spirits. My findings to date are pretty conclusive that we are on to something of prime importance regarding the brain. Briefly, and in layman's language, the chemistry within the brain cells concerned with memory, everything we have done from infancy onwards, is reproducible, returnable, for want of a better term, in these same cells, the exact contents of which depends upon our hereditary make-up, the legacy of parents, grandparents, remoter ancestors back to primeval times. The fact that I am a genius and you are a lay-about depends solely upon the messages transmitted to us from these cells and then distributed through the various other cells and throughout our body, but, our various characteristics apart, the particular cells I have been working upon — which I will call the memory-boxstore — not only our own memories but habits of the earlier brain pattern we inherit. These habits, if released to consciousness, would enable us to see, hear, become cognoscent of things that happened in the past, not because any particular ancestor witnessed any particular scene, but because with the use of a medium — in this case a drug — the inherited, older brain pattern takes over and becomes dominant. The implications from a historian's point of view don't concern me, but, biologically, the potential uses of the hitherto untapped ancestral brain are of enormous interest, and open immeasurable possibilities.

'As to the drug itself, yes, it's dangerous, and could be lethal if taken to excess, and should it fall into the hands of the unscrupulous it might bring even more havoc upon our already troubled world. So, dear boy, if anything happens to me, destroy what remains in Bluebeard's chamber. My staff — who, however, know nothing of the implications of my discovery, for I have been working on this on my own — have similar instructions here in London, and can be trusted implicitly. As to yourself, if I don't see you again, forget the whole business. If we meet this evening as arranged, and take a walk and perhaps a trip together, as I hope we shall, I intend to have a close look, if I have the luck, at the beautiful Isolda, who, from the evidence in the document at the top of my suitcase, appears to have lost her lover just as you said, and must be in dire need of consolation. Whether Roger Kylmerth can supply it we may discover at the same time. No time to say any more, we are drawing into Exeter.

A bient+¦t, in this world, or the other, or hereafter.

Magnus.'

If we had not gone sailing on the Friday I should have found the telephone message about the earlier train in time… If I had made straight for the Gratten after leaving Saint Austell station, instead of going home… Too many ifs, and none of them working out. Even this letter, coming now like a message from the dead, should have reached me on Saturday morning instead of today, Monday. Not that it would have done any good. Nor did it say anything about Magnus's real intentions. Even then, as he posted it, he may not have made up his mind. The letter was a safety-measure, as he said, in case anything went wrong. I read it through again, once, twice, then put my lighter to it and watched it burn.

I went down to the basement and through the old kitchen to the lab. I had not entered it since early Wednesday morning, after returning from the Gratten, when Bill had come downstairs and found me making tea in the kitchen. The rows of jars and bottles, the monkey's head, the embryo kittens and the fungus plants held no menace for me now, nor had they done so since the first experiment. Now, with their magician gone, never to return, they had a wasted, almost a forlorn appearance, like puppets and props from a conjurer's bag of tricks. No ebony wand would bring these things to life, no cunning hand extract the juices, pick the bones and set them fermenting in some bubbling cauldron brew.

I took the jars which held various liquids and poured the contents down the sink. Then I washed the jars out and put them back on the shelf. They could have been used for preserving fruit or jam, for all anybody would ever know; there were no distinctive marks upon them — only labels which I stripped off and pocketed. Then I fetched an old sack which I remembered seeing in the boiler-house, and set about unscrewing the remaining jars and bottles that contained the embryos and the monkey's head. I put them all in the sack, having first poured down the sink the liquid that had preserved them, taking care that none of it touched my hands. I did the same with the various fungi, putting them also in the sack. Only two small bottles remained, bottle A, containing the remains of the drug I had been using myself to date, and bottle C, untouched. Bottle B I had sent to Magnus, and it was lying empty in my suitcase upstairs. I did not pour the contents of either down the sink. I put them in my pocket. Then I went to the door and listened. Mrs. Collins was moving about between the kitchen and the pantry — I could hear her radio going.

I swung the sack over my shoulder and locked the door of the lab. Then I went out through the back door and climbed up to the kitchen garden behind the stable block, and into the wood at the top of the grounds. I went to where the undergrowth was thickest, straggling laurels, rhododendrons that had not bloomed for years, broken branches of dead trees, brambles, nettles, the fallen leaves of successive autumn gales, and I took one of the dead branches and scraped a pit in the wet, dank earth and emptied the sack into it, smashing the monkey's head with a jagged stone so that it no longer bore any resemblance to a living thing, only fragments, only jelly, and the embryos slithered amongst the fragments, unrecognisable, like the stringy entrails flung to a seagull when a fish is gutted. I covered them, and the sack, with the rotting leaves of years, and the brown earth, and a heap of nettles, and the sentence came into my mind, 'Ashes to ashes, dust to dust', and in a sense it was as if I were burying Magnus and his work as well. I went back into the house, through the basement, and up the little side-stairway to the front, thus avoiding Mrs. Collins, but she must have heard me entering the hall, for she called, "Is that you, Mr. Young?"

"Yes," I said.

"I looked for you everywhere — I couldn't find you. The Inspector from Liskeard was on the telephone."

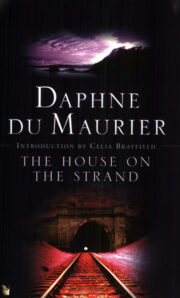

"The House on the Strand" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The House on the Strand". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The House on the Strand" друзьям в соцсетях.