He stood in the hall, listening. There was no one there but our two selves, and looking about me I sensed that the place had somehow changed since that day in May when Henry Champernoune had died; it no longer had the feeling of permanent occupancy, but more of a house where the owners came and went, leaving it empty in their absence. There was no sound of barking dogs, no sign of servants, other than the children's nurse, and it came to me suddenly that the lady of the house herself, Joanna Champernoune, must be away from home with her own brood of sons and daughter, perhaps in that other manor of Trelawn, which the steward had mentioned to Lampetho and Trefrengy in the Kilmarth kitchen on the night of the abortive rebellion. Roger must be in charge, and Isolda's children and their nurse were here to break their journey between one house and another.

He crossed over to the window, through which the late sunlight came, and looked out. Almost at once he flattened himself against the wall as though someone from outside might catch sight of him, and he preferred to remain unseen. Intrigued, I also ventured to the window, and immediately guessed the reason for his manoeuvre. There was a bench beneath the window, with two people sitting on it, Isolda and Otto Bodrugan, and because of the angle of the wall, which jutted outward, giving the bench shelter, anyone who sat there would have privacy unless he was spied upon from this one window.

The grass beneath the bench sloped to a low wall, and beyond the wall the fields descended to the river where Bodrugan's ship was anchored.

I could see the mast-head, but not the deck. The tide was low, the channel narrow, and on either side of the blue ribbon of water were sand-flats, crowded with every sort of wading bird, dipping and bobbing around the pools where the tide had ebbed. Bodrugan held Isolda's hands in his, examining the fingers, and in a foolish sort of love-play bit each one of them in turn, or rather made pretence of biting them, grimacing as he did so as though they tasted sour.

I stood by the window watching them, oddly disturbed, not because I, like the steward, was playing spy, but because I sensed in some fashion that the relationship between these two, however passionate it might be at other times, was at this moment innocent, without guile and altogether blessed, and it was the kind of relationship that I myself would never know. Then suddenly he released both hands, letting them drop on to her lap.

"Let me stay another night and not sleep aboard," he said. "In any event the tide may serve me ill, and I may find myself hard aground if I make sail."

"Not if you choose your moment," she replied. "The longer you remain here the more dangerous for us both. You know how gossip travels. To come here anyway was madness, with the vessel well known."

"There's nothing to that," he said. "I come frequently to the bay and to this river, either on business or for my own pleasure, fishing between here and Chapel Point. It was pure chance that brought you here as well."

"It was not," she said, "and you know it very well. The steward brought you my letter telling you I should be here."

"Roger is a trusty messenger," he answered. "My wife and children are at Trelawn, and so is my sister Joanna. The risk was worth the taking."

"Worth taking, yes, this once, but not for two nights in succession. Nor do I trust the steward as you do, and you know my reasons."

"Henry's death, you mean?" He frowned. "I still think you judged unfairly there. Henry was a dying man. We all knew it. If those potions made him sleep the sooner, free from pain and with Joanna's knowledge, why should we shake our heads?"

"Too easy done," she said, "and with intent. I'm sorry for it, Otto, but I cannot forgive Joanna, even if she is your sister. As for the steward, doubtless she paid him well, and his monk accomplice." I glanced at Roger. He had not moved from his shadowed corner by the window, but he could hear them as well as I did, and judging by the expression in his eyes he hardly relished what she said.

"As to the monk," added Isolda, "he is still at the Priory, and adds something to his influence every day. The Prior is wax in his hands, and his flock do as they are bidden by Brother Jean, who comes and goes as he pleases."

"If he does so", said Bodrugan, "it is no concern of mine."

"It could become so," she told him, "if Margaret comes to have as much faith in his herbal knowledge as Joanna. You know he has treated your family lately?"

"I know nothing of the sort," he answered. "I have been at Lundy, as you know, and Margaret finds both the island and Bodrugan too exposed, and prefers Trelawn." He rose from the bench and began pacing up and down the grass walk in front of her. Love-making was over, with the problems of domestic life upon them once again. They had my sympathy. "Margaret is too much a Champernoune, like poor Henry," he said. "A priest or a monk could persuade her to abstinence or perpetual prayer if he had the mind to do so. I shall look into it."

Isolda also rose from the bench, and standing close to Bodrugan looked up at him, with her hands upon his shoulders. I could have touched them both had I leant from the window. How small they were, inches below adult height today, yet he was broadly-built and strong, with a fine head and a most likable smile, and she as delicately formed as a porcelain shepherdess, hardly taller than her own daughters. They held each other, kissing, and once again I felt this strange disturbance, a sense of loss, utterly unlike anything I might experience in my own time, had I seen two lovers from a window… Intense involvement, and intense compassion too. Yes, that was the word, compassion. And I had no way of explaining my sense of participation in all they did, unless it was that stepping backwards, out of my time to theirs, I felt them vulnerable, and more certainly doomed to die than I was myself knowing indeed that they had both been dust for more than six centuries. "Have a care for Joanna, too," said Isolda. "She is no nearer being married to John now than she was two years ago, and has altered for the worse in consequence. She might even serve his wife as she served her husband."

"She would not dare, nor John," answered Bodrugan.

"She would dare anything if it suited her. Harm you likewise, if you stood in her way. She has one thought in mind, to see John Keeper of Restormel and Sheriff of Cornwall, and herself his wife, queening it over all the crown lands as Lady Carminowe."

"If it should come about I can't prevent it," protested Bodrugan.

"As her brother you could try," said Isolda, "and at least prevent that monk from trailing at her heels with his poisonous draughts."

"Joanna was always headstrong," replied her lover. "She has always done as she pleased. I cannot be on watch continually. I might say a word to Roger."

"To the steward? He is as thick with the monk as she," said Isolda scornfully. "I warn you again, don't trust him, Otto. Neither on her account, nor on ours. He keeps our few meetings secret for the time because it pleases him."

Once again I glanced at Roger, and saw the shadow on his face. I wished someone would call him from the room so that he could no longer play eavesdropper. It would put him against her to hear his faults so plainly stated and with such dislike.

"He stood by me last October and will do so again," said Bodrugan.

"He stood by you then because he reckoned he had much to gain," replied Isolda. "Now you can do little for him, why should he risk losing his position? One word to Joanna, and thence to John, and thence to Oliver, and we'd be lost."

"Oliver is in London."

"London today, perhaps. But malice travels with every wind that blows. Tomorrow Bere or Bockenod. The next day Tregest or Carminowe. Oliver cares not a jot if I live or die, he has women wherever he goes, but his pride would never brook a faithless wife. And that I know." A cloud had come between them, and in the sky too, gathering above the hills beyond the valley. All the brightness of the summer day had gone. Innocence had vanished, and with it the serenity of their world. Mine too. Separated by centuries, I somehow shared their guilt.

"How late is it?" she asked.

"Near six, by the sun," he answered. "Does it matter?"

"The children should be away with Alice," she said. "They may come running to find me, and they must not see you here."

"Roger is with them," he told her, "he will take care they leave us alone."

"Nevertheless, I must bid them goodnight, or they will never mount their ponies."

She began to move away along the grass, and as she did so the steward also slipped from his dark corner and crossed the hail. I followed, puzzled. They could not be staying in the house after all but somewhere else, at Bockenod, perhaps. But the Boconnoc I knew was a longish ride for children on ponies in late afternoon; they would hardly reach it before dusk. We went through the hallway to the open court beyond, and through the archway to the stables. Roger's brother Robbie was there, saddling the ponies, helping the little girls to mount, laughing and joking with the nurse who, propped high on her own steed, had some trouble in making it stand still.

"He'll go quietly enough with two of you on his back," called Roger. "Robbie shall sit on the pony with you and keep you warm. Before you or behind you, state your preference. It's all the same to him, isn't it, Robbie?"

The nurse, a country girl with flaming cheeks, gawked delightedly, protesting she could ride very well alone, and there was further giggling, instantly silenced with a frown from Roger as Isolda came into the stable yard. He moved to her side, head bent in deference.

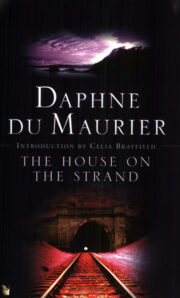

"The House on the Strand" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The House on the Strand". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The House on the Strand" друзьям в соцсетях.