"I was up very early," I said. "I went for a walk."

"What, in all this rain? You must be crazy. Look, your trousers are torn, and there's a great rent in your jacket."

She seized hold of my arm and the boys crowded round me, gaping. Vita began to laugh. "Where on earth did you go to get in a state like this?" she asked.

I shook myself clear. "Look," I said, "we'd better unload. It's no good doing it here — the front door is locked. Hop in the car and we'll go round to the back."

I led the way with the boys, and she followed in the car. When we reached the back entrance I remembered that it was locked too from the inside — I had left the house by the patio.

"Wait here," I said, "I'll open the door for you," and with the boys in close attendance I went round to the patio. The boiler-house door was ajar — I must have passed through it when I followed Roger and the rest of the conspirators. I kept telling myself to keep calm, not to get confused; if confusion started in my mind it would be fatal.

"What a funny old place. What's it for?" asked Micky.

"To sit in", I said, "and sun-bathe. When there is any sun."

"If I were Professor Lane I'd turn it into a swimming pool," said Teddy. They trooped after me into the house, and through the old kitchen to the back door. I unlocked it, and found Vita waiting impatiently outside.

"Get in out of the rain", I said, "while the boys and I fetch in the suitcases."

"Show us round first," she said plaintively. "The luggage can wait. I want to see everything. Don't tell me that is the kitchen through there?"

"Of course it isn't," I said. "It's an old basement kitchen. We don't use any of this." The thing was, I had never intended to show them the house from this angle. It was the wrong way round. If they had arrived on Monday I should have been waiting for them on the steps by the porch, with the curtains drawn back, the windows open, everything ready. The boys, excited, were already scampering up the stairs.

"Which is our room?" they shouted. "Where are we to sleep." Oh God, I thought, give me patience. I turned to Vita, who was watching me with a smile.

"I'm sorry, darling," I said, "but honestly—"

"Honestly what?" she said. "I'm as excited as they are. What are you fussing about?"

What indeed! I thought, with total inconsequence, how much better organised this would have been if Roger Kylmerth, as steward, had been showing Isolda Carminowe the lay-out of some manor house.

"Nothing," I said, "come on…"

The first thing Vita noticed when we reached the modern kitchen on the first floor was the debris of my supper on the table. The remains of fried eggs and sausages, the frying-pan not cleaned, standing on one corner of the table, the electric light still on.

"Heavens!" she exclaimed. "Did you have a cooked breakfast before your walk? That's new for you!"

"I was hungry," I said. "Ignore the mess, Mrs. Collins will clear all that. Come through to the front."

I hurried past her to the music-room, drawing curtains, throwing back shutters, and then across the hall to the small dining-room and the library beyond. The piece de r+®sistance, the view from the end window, was blotted out by the mizzling rain.

"It looks different", I said, "on a fine day."

"It's lovely," said Vita. "I didn't think your Professor had such taste. It would be better with that divan against the wall and cushions on the window-seat, but that's easily done."

"Well, this completes the ground-floor," I said. "Come upstairs."

I felt like a house-agent trying to flog a difficult let, as the boys raced ahead up the stairs, calling to each other from the rooms, while Vita and I followed. Everything had already changed, the silence and the peace had gone, henceforth it would be only this, the take-over of something I had shared, as it were, in secret, not only with Magnus and his dead parents in the immediate past, but with Roger Kylmerth six hundred years ago.

The tour of the first floor finished, the sweat of unloading all the luggage began, and it was nearly half-past eight when the job was done, and Mrs. Collins arrived on her bicycle to take charge of the situation, greeting Vita and the boys with genuine delight. Everyone disappeared into the kitchen. I went upstairs and ran the bath, wishing I could lie in it and drown.

It must have been half an hour later that Vita wandered into the bedroom. "Well, thank God for her," she said. "I shan't have to do a thing, she's extremely efficient. And must be sixty at least. I can relax."

"What do you mean, relax?" I called from the bathroom. "I imagined something young and skittish, when you tried to put me off from coming down," she said. She came into the bathroom as I was rubbing myself with the towel. "I don't trust your Professor an inch, but at least I'm satisfied on that account. Now you're all cleaned up you can kiss me again, and then run me a bath. I've been driving for seven hours and I'm dead to the world."

So was I, but in another sense. I was dead to her world. I might move about in it, mechanically, listening with half an ear as she peeled off her clothes and flung them on the bed, put on a wrapper, spread her lotions and creams on the dressing-table, chatting all the while about the drive down, the day in London, happenings in New York, her brother's business affairs, a dozen things that formed the pattern of her life, our life; but none of them concerned me. It was like hearing background music on the radio. I wanted to recapture the lost night and the darkness, the wind blowing down the valley, the sound of the sea breaking on the shore below Polpey farm, and the expression in Isolda's eyes as she looked out of that painted wagon at Bodrugan.

"…And if they do amalgamate it wouldn't be before the fall anyway, nor would it affect your job."

Response was automatic to the rise and fall of her voice, and suddenly she wheeled round, her face a mask of cream under the turban she always wore in the bath, and said, "You haven't been listening to a word I said!"

The change of tone shocked me to attention. "Yes, I have," I told her.

"What, then? What have I been talking about?" she challenged. I was clearing my things out of the wardrobe in the bedroom, so that she could take over. "You were saying something about Joe's firm," I answered, "a merger of some sort. Sorry, darling, I'll be out of your way in a minute."

She seized the hanger bearing a flannel suit, my best, out of my hand, and hurled it on the floor.

"I don't want you out of the way," she said, her voice rising to a pitch I dreaded. "I want you here and now, giving me your full attention, instead of standing there like a tailor's dummy. What on earth's the matter with you? I might be talking to someone in another world." She was so right. I knew it was no use counter-attacking; I must grovel, and let her tide of perfectly justifiable irritation pass over my head.

"Darling," I said, sitting down on the bed and pulling her beside me, "let's not start the day wrong. You're tired, I'm tired; if we start arguing we'll wear ourselves out and spoil things for the boys. If I am vague and inattentive, you must blame it on exhaustion. I took that walk in the rain because I couldn't sleep, and instead of pulling me together it seems to have slowed me up."

"Of all the idiotic things to do — You might have known… And anyway, why couldn't you sleep?"

"Forget it, forget it, forget it."

I rose from the bed, seized armfuls of clothes and bore them through to the dressing-room, kicking the door to with my foot. She did not follow me. I heard her turn the taps off and get into the bath, slopping the water so that some of it ran into the overflow. The morning drifted on. Vita did not appear. I opened the bedroom door very softly just before one, and she was fast asleep on the bed, so I closed it again and lunched downstairs alone with the boys. They chatted away, perfectly content with a 'yes' or 'perhaps' from me, invariably undemanding when Vita was absent. It continued to rain steadily, and there was no question of cricket or the beach, so I drove them into Fowey and let them loose to buy ice-creams, peppermint rock, western paperbacks and jig-saw puzzles. The rain petered out about four, giving place to a lustre-less sky and a pallid, constipated sun, but this was enough for the boys, who rushed on to the Town Quay and demanded to be water-born. Anything to please, and postpone the moment of return, so I hired a small boat, powered by an outboard engine, and we chug-chugged up and down the harbour, the boys snatching at passing flotsam as we bobbed about, all of us soaked to the skin.

We arrived home about six o'clock, and the children rushed to sit down to the enormous spread of tea that the thoughtful Mrs. Collins had provided for them. I staggered into the library to pour myself a stiff whisky, only to find a revitalised Vita in possession, smiling, the furniture all moved around, the morning mood, thank heaven, a thing of the past.

"You know, darling," she said, I" think I'm going to like it here. Already it's beginning to look like home." I collapsed into an armchair, drink in hand, and watched through half-closed eyes as she pottered about the room rearranging Mrs. Collins brave efforts with the hydrangeas. My strategy henceforth would be to applaud everything, or, when occasion demanded silence, to stay mute, play each moment as it came by ear. I was on my second whisky, and off my guard, when the boys burst into the library.

"Hi, Dick," shouted Teddy, "what's this horrible thing?" He had got the embryo monkey in its jar. I leapt to my feet. "Christ!" I said. "What the hell have you been up to?"

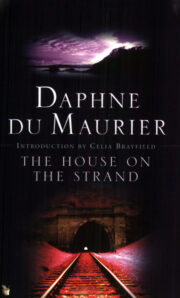

"The House on the Strand" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The House on the Strand". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The House on the Strand" друзьям в соцсетях.