I would have stood and stared, the setting had such beauty and simplicity, but my horseman travelled on, and compulsion to follow sent me after him. The track descended to the green, and now the village life was all about me; there were women by the well at the near corner of the green, their long skirts caught up round the waist, their heads bound with cloth covering them to the chin, so that nothing showed but eyes and nose. The arrival of my horseman created disturbance. Dogs started barking, more women appeared from the dwellings that now, on closer inspection, proyed to be little more than hovels, and there was a calling to and fro across the green, the voices, despite the uncouth clash of consonants, ringing with the unmistakable Cornish burr. The rider turned left, dismounted before the walled enclosure, flung his reins over a staple in the ground, and entered through a broad, brass-studded doorway. Above the arch there was a carving showing the robed figure of a saint, holding in his right hand the cross of Saint Andrew. My Catholic training, long forgotten, even mocked, made me cross myself before that door, and as I did so a bell sounded from within, striking so profound a chord in my memory that I hesitated before entering, dreading the old power that might turn me back into the childhood mould.

I need not have worried. The scene that met my eyes was not that of orderly paths and quadrangles, quiet cloisters, the odour of sanctity, the silence born of prayer. The gate opened upon a muddied yard, round which two men were chasing a frightened boy, flicking at his bare thighs with flails. Both, from their dress and tonsure, were monks, and the boy a novice, his skirt secured above his waist to make their sport more piquant.

The horseman watched the pantomime unmoved, but when the boy at last fell, his habit about his ears, his skinny limbs and bare backside exposed, he called, "Don't bleed him yet. The Prior likes sucking-pig served without sauce. The garnish will come later when the piglet turns tough." Meanwhile the bell for prayer continued, without effect upon the sportsmen in the yard.

My horseman, his sally applauded, crossed the yard and entered the building that lay before us, turning into a passage-way which seemed to divide kitchen from refectory, judging by the smell of rancid fowl, only partly sweetened by turf smoke from the fire. Ignoring the warmth and savour of the kitchen to the right, and the colder comfort of the refectory with its bare benches on his left, he pushed through a centre door and up a flight of steps to a higher level, where the passage was barred by yet another door. He knocked upon it, and without waiting for an answer walked inside.

The room, with timbered roof and plastered walls, had some semblance of comfort, but the scrubbed and polished austerity, a vivid memory of my own childhood, was totally absent. This rush-strewn floor was littered with discarded bones half-chewed by dogs, and the bed in the far corner, with its musty hangings, appeared to serve as a general depository for dumped goods — a rug made from a sheep's coat, a pair of sandals, a rounded cheese on a tin plate, a fishing-rod, with a greyhound scratching itself in the midst of all.

"Greetings, Father Prior," said my horseman.

Something rose to a sitting posture in the bed, disturbing the greyhound, which leapt to the floor, and the something was an elderly, pink-cheeked monk, startled from his sleep.

"I left orders I was not to be disturbed," he said. My horseman shrugged. "Not even for the Office?" he asked, and put out his hand to the dog, which crept beside him, wagging a bitten tail. The sarcasm brought no reply. The Prior dragged his coverings closer, humping his knees beneath him. "I need rest," he said, "all the rest possible, to be in a fit state to receive the Bishop. You have heard the news?"

"There are always rumours," answered the horseman.

"This was not rumour. Sir John sent the message yesterday. The Bishop has already set out from Exeter and will be here on Monday, expecting hospitality and shelter for the night with us, after leaving Launceston."

The horseman smiled. "The Bishop times his visit well. Martinmas, and fresh meat killed for his dinner. He'll sleep with his belly full, you've no cause for worry."

"No cause for worry?" The Prior's petulant voice touched a higher key. "You think I can control my unruly mob? What kind of impression will they make upon that new broom of a Bishop, primed as he is to sweep the whole Diocese clean?"

"They'll come to heel if you promise them reward for seemly behaviour. Keep in the good graces of Sir John Carminowe, that's all that matters."

The Prior moved restlessly beneath his covers. "Sir John is not easily fooled, and he has his own way to make, with a foot in every camp. Our patron he may be, but he won't stand by me if it doesn't suit his ends."

The horseman picked up a bone from the rushes, and gave it to the dog. "Sir Henry, as lord of the manor, will take precedence over Sir John on this occasion," he said. "He'll not disgrace you, garbed like a penitent. I warrant he is on his knees in the chapel now."

The Prior was not amused. "As the lord's steward you should show more respect for him," he observed, then added thoughtfully, "Henry de Champernoune is a more faithful man of God than I."

The horseman laughed. "The spirit is willing, Father Prior, but the flesh?" He fondled the greyhound's ear. "Best not talk about the flesh before the Bishop's visit." Then he straightened himself and walked towards the bed. "The French ship is lying off Kylmerth. She'll be there for two more tides if you want to give me letters for her."

The Prior thrust off his covers and scrambled from the bed. "Why in the name of blessed Antony did you not say so at once?" he cried, and began to rummage amongst the litter of assorted papers on the bench beside him. He presented a sorry sight in his shift, with spindle legs mottled with varicose veins, and hammer-toed, singularly dirty feet. "I can find nothing in this jumble," he complained. "Why are my papers never in order? Why is Brother Jean never here when I require him?" He seized a bell from the bench and rang it, exclaiming in protest at the horseman, who was laughing again. Almost at once a monk entered: from his prompt response he must have been listening at the door. He was young and dark, and possessed a pair of remarkably brilliant eyes.

"At your service, Father," he said in French, and before he crossed the room to the Prior's side exchanged a wink with the horseman.

"Come, then, don't dally," fretted the Prior, turning back to the bench. "I'll bring the letters later tonight, and instruct you further in the arts you wish to learn."

The horseman bowed in mock acknowledgement, and moved towards the door. "Goodnight, Father Prior. Lose no sleep over the Bishop's visit. Goodnight, Roger, goodnight. God be with you."

As we left the room together the horseman sniffed the air with a grimace. The mustiness of the Prior's chamber had now an additional spice, a whiff of perfume from the French monk's habit.

We descended the stairs, but before returning through the passage-way the horseman paused a moment, then opened another door and glanced inside. The door gave entrance to the chapel, and the monks who had been playing pantomime with the novice were now at prayer. Or, to describe it more justly, making motion of prayer. Their eyes were downcast, and their lips moved. There were four others present whom I had not seen in the yard, and of these two were fast asleep in their stalls. The novice himself was huddled on his knees, crying silently but bitterly. The only figure with any dignity was that of a middle-aged man, dressed in a long mantle, his grey locks framing a kindly, gracious face. With hands clasped reverently before him, he kept his eyes steadfast on the altar. This, I thought, must be Sir Henry de Champernoune, lord of the manor and my horseman's master, of whose piety the Prior had spoken.

The horseman closed the door and went out into the passage, and so from the building and across the now empty yard to the gate. The green was deserted, for the women had left the well, and there were clouds in the sky, a sense of fading day. The horseman mounted his pony and turned for the track through the upper plough-lands.

I had no idea of time, his time or mine. I was still without sense of touch, and could move beside him without effort. We descended the track to the ford, which he traversed now without wetting his pony's hocks, for the tide had ebbed, and struck upward across the further fields. When we reached the top of the hill and the fields took on their familiar shape I realised, with growing excitement and surprise, that he was leading me home, for Kilmarth, the house which Magnus had lent me for the summer holidays, lay beyond the little wood ahead of us. Some six or seven ponies were grazing close by, and at sight of the horseman one of them lifted his head and whinnied; then with one accord they swerved, kicked up their heels, and scampered away. He rode on through a clearing in the wood, the track dipped, and there immediately below us in the hollow lay a dwelling, stone-built, thatched, encircled by a yard deep in mud. Piggery and byre formed part of the dwelling, and through a single aperture in the thatch the blue smoke curled. I recognised one thing only, the scoop of land in which the dwelling lay. The horseman rode down into the yard, dismounted and called, and a boy came out of the adjoining cow-house to take the pony. He was younger, slighter than my horseman, but had the same deep-set eyes, and must have been his brother. He led the pony on and the horseman passed through the open doorway into the house, which seemed at first sight to consist of one room only. Following close behind, I could distinguish little through the smoke, except that the walls were built of the mixture of clay and straw that they call cob, and the floor was plain earth, without even rushes upon it.

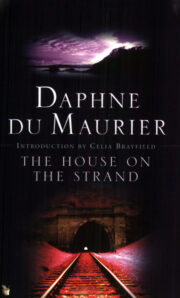

"The House on the Strand" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The House on the Strand". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The House on the Strand" друзьям в соцсетях.