There were two letters on my breakfast-tray. One was from my mother in Shropshire saying how lovely it must be in Cornwall and she envied me, I must be getting so much sun. Her arthritis had been bad again and poor old Dobsie was getting very deaf. (Dobsie was my step-father, and I didn't wonder he was deaf; it was probably a defence mechanism, for my mother never drew breath.) And so on and so on, her large looped handwriting covering about eight pages. Pangs of conscience, for I had not seen her for a year, but to give her her due she never reproached me, was delighted when I married Vita, and always remembered the boys at Christmas with what I considered an unnecessarily thumping tip. The other envelope was long and slim, and contained a couple of typewritten documents and a note scribbled by Magnus.

Dear Dick, it read, my disciple's long-haired friend who spends his time browsing around the B.M. and the P.R.O. had produced the enclosed when I arrived at my desk this morning. The copy of the Lay Subsidy Roll is quite informative, and the other, mentioning your lord of the manor, Champernoune, and the to-do about removing his body may amuse you.

I shall think about you this afternoon and wonder if Virgil is leading Dante astray. Do remember not to touch him; the reaction can be progressively unpleasant. Keep your distance and all will be well. I suggest you stay put on the premises for your next trip.

Yours, Magnus.

I turned to the documents. The research student had scribbled at the top of the first, From Bishop Grandisson of Exeter. Original in Latin. Excuse my translation. It read as follows:

Grandisson. A.D. 1329. Tywardreath Priory.

John, etc., to his beloved sons men of a religious order, the Lords, the Prior and Convent of Tywardreath, greetings, etc.

By the laws of the sacred Canons it is known that we are warned that the bodies of the Faithful, once delivered for burial by the Church, may not be exhumed except by those same laws. It has lately come to our ears that the body of the Lord Henry of Champernoune, Knight, rests buried in your consecrated church. Certain men, however, directing their mind's eyes in worldly fashion upon the transitory pomps of this life rather than on the welfare of the said Knight's soul and the discharging of due rites, are busying themselves about the exhumation of the said body, in circumstances not permitted by our laws, and about removing it to another place without our licence. Wherefore strictly enjoining upon you the virtue of obedience we give orders that you, in resistance to such reckless daring, must not allow the exhumation of the said body or its removal to be undertaken in any way, when we have not been consulted, nor have the reasons for such exhumation or removal, if there were any, been examined, discussed, or approved; even as you wish to escape divine retribution or that of ourselves. While we for our part lay an inhibition on all and each of our subjects, and no less upon others through whom it is hoped apparently to perpetrate a crime of this kind, so that they should not, under pain of excommunication, afford any help, counsel or favour for such an exhumation or removal of this kind which is in question.

Given at Paignton on the 27th of August.

Magnus had added a foot-note.

I like Bishop Grandisson's forthright style. But what is it all about? A family squabble, or something more sinister, of which the Bishop himself was ignorant?

The second document was a list of names, headed Lay Subsidy Roll, 1327, Paroch Tiwardrayd. Subsidy of a twentieth of all moveable goods, upon all the Commons who possess goods of the value of ten shillings or upwards. Then were forty names in all, and Henry de Champernoune headed the list. I ran my eye down the rest. Number twenty-three was Roger Kylmerth. So it wasn't hallucination — he had really lived.

CHAPTER EIGHT

WHEN I HAD dressed I went to the garage and fetched the car, and skirting Tywardreath took the road to Treesmill. I purposely avoided the lay-by and drove down the hill into the valley, but not before the fellow at the bungalow Chapel Down, who was busy washing his caravan, waved a hand in greeting. The same thing happened when I stopped the car below the bridge near Treesmill Farm. The farmer of yesterday morning was driving his cows across the road, and paused to speak to me. I thanked my stars neither of them had been at the lay-by later in the day.

"Found your manor house yet?" he asked.

"I'm not sure," I told him. "I thought I'd take another look round. That's a curious sort of place half-way up the field there, covered in gorse-bushes. Has it got a name?"

I could not see the site from the bridge, but pointed roughly in the direction of the quarry where yesterday, in another century, I had followed Roger into the house where Sir Henry Champernoune lay dying.

"You mean up Gratten?" he said. "I don't think you'll find anything up there except old slate and rubble. Fine place for slate, or was. Mostly rubbish now. They say when the houses were built in Tywardreath in the last century they took most of the stones and slates from that place. It may be true."

"Why Gratten?" I asked.

"I don't know exactly. The ploughed field at the back is the Gratten, part of Mount Bennett farm. The name has something to do with burning, I believe. There's a path opposite the turning to Stonybridge will lead you to it. But you'll find nothing to interest you."

"I don't suppose I shall," I answered, "except the view."

"Mostly trains," he laughed, "and not so many of them these days."

I parked the car half-way up the hill, opposite the lane, as he suggested, then struck across the field towards the Gratten. The railway and the valley were beneath me, to my right, the ground descending very steeply to a high embankment beside the railway, then sloping away more gradually to swamp and thicket. Yesterday, in that other world, there had been a quayside midway between the two, and in the centre of the wooded valley, where trees and bush were thickest, Otto Bodrugan had anchored his craft mid-channel, the bows of the boat swinging to meet the tide. I passed the spot below the hedge where I had sat and smoked my cigarette. Then I went through the broken gate, and stood once more amongst the hillocks and the mounds. Today, without vertigo or nausea, I could see more clearly that these knolls were not the natural formation of uneven ground, but must have been walls that had been covered for centuries by vegetation, and the hollows which I had thought, in my dizziness, to be pits were simply the enclosures that long ago had been rooms within a house.

The people who had come to gather slates and stones for their cottages had done so for good reason. Digging into the soil that must have covered the foundations of a building long vanished would have given them much of the material they needed for their own use, and the quarry at the back was part of this same excavation. Now, the quest ended, the quarry remained a tip for useless junk, the discarded tins rusted with age and winter rains.

Their quest had ended, while mine had just begun, but, as the farmer down at Treesmill had warned me, I should find nothing. I knew only that yesterday, in another time, I had stood in the vaulted hall that formed the central feature of this long-buried house, had mounted the outer stairway to the room above, had seen the owner of the dwelling die. No courtyard now, no walls, no hail, no stable- quarters in the rear; nothing but grassy banks and a little muddy path running between them.

There was a patch of even ground, smooth and green, fronting the site, that might have been part of the courtyard once, and I sat down there looking into the valley below as Bodrugan had done from the small window in the hall. Tiwardrai, the House on the Strand… I thought how, when the tide ebbed in early centuries, the twisting channel would stay blue, revealing sandy flats on either side of it, these flats a burnished gold under the sun. If the channel was deep enough, Bodrugan could have raised anchor and made for sea later that night; if not, he would have returned on board to sleep amongst his men, and at daybreak, perhaps, come out on deck to stretch himself and stare up at the house of mourning. I had put the documents that had come by post this morning into my pocket, and now I drew them out and read them through again. Bishop Grandisson's order to the Prior was dated August, 1329. Sir Henry Champernoune had died in late April or early May. The Ferrers pair were doubtless behind the attempt to remove him from his Priory tomb, with Matilda Ferrers the more pressing of the two. I wondered who had carried the rumour to the Bishop's ears, so playing on ecclesiastical pride, and ensuring that the body would escape investigation? Sir John Carminowe, in all probability, acting hand in glove with Joanna — whom he had, no doubt, long since successfully taken to bed.

I turned to the Lay Subsidy Roll, and glanced once again through the list of names, ticking off those that corresponded to the place-names on the road map I had brought from the car. Ric Trevynor, Ric Trewiryan, Ric Trenathelon, Julian Polpey, John Polorman, Geoffrey Lampetho… all, with slight variations in the spelling, were farms marked on the roadmap beside me. The men who dwelt in them then, dead for over six hundred years, had bequeathed their names to posterity; only henry Champernoune, lord of the manor, had left a heap of mounds as legacy, to be stumbled upon by myself; a trespasser in time. All dead for nearly seven centuries, Roger Kylmerth and Isolda Carminowe amongst them. What they had dreamt of; schemed for, accomplished, no longer mattered, it was all forgotten. I got up and tried to find, amongst the mounds, the hall where Isolda had sat yesterday, accusing Roger of complicity in crime. Nothing fitted. Nature had done her work too well, here on the hillside and below me in the valley, where the estuary once ran. The sea had withdrawn from the land, the grass had covered the walls, the men and women who had walked here once, looking down upon blue water, had long since crumbled into dust.

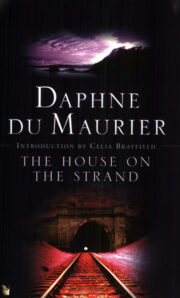

"The House on the Strand" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The House on the Strand". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The House on the Strand" друзьям в соцсетях.