It was one of our first rows, and I did not know how to deal with it.

She wandered around the sitting-room punching cushions and emptying her own ash-trays, while I sat on the sofa looking aggrieved. We went to bed without speaking, but the next morning, to my surprise and relief she behaved as if nothing had happened, and positively glowed with feminine warmth and charm. Magnus was not mentioned again, but I made a mental note not to dine with him again unless she had a date herself elsewhere.

Today I did not feel like a pricked balloon when he rang off — the expression was rather offensive, come to think of it, suggesting the foetid air of somebody's breath exploding — merely denuded of stimulation, and a little uneasy too, because why did he suddenly want a test done on the bottle marked B? Did he want to make certain of his findings on the unfortunate monkey before putting me, the human guinea-pig, to a possibly sharper test? There was still sufficient solution in bottle A to keep me going…

I was brought up sharply in my train of thought. Keep me going? It sounded like an alcoholic preparing for a spree, and I remembered what Magnus had said about the possibilities of the drug being addictive. Perhaps this was another reason for trying it out on the monkey. I had a vision of the creature, bleary-eyed, leaping about his cage and panting for the next injection.

I felt in my pocket for the flask, and rinsed it out very thoroughly. I did not replace it on the pantry shelf however, for Mrs. Collins might take it into her head to move it somewhere else, and then if I happened to want it I should have to ask her where it was, which would be a bore. It was too early for supper, but the tray she had laid with ham and salad, fruit and cheese looked tempting, and I decided to carry it into the music-room and have a long evening by the wood fire. I took a stack of records at random and piled them one on top of the other on the turn-table. But, no matter what sounds filled the music-room, I kept returning to the scenes of this afternoon, the reception in the Priory chapter-house, the stripping of carcasses on the village green, the hooded musician with his double horn wandering amongst the children and the barking dogs, and above all that lass with braided hair and jewelled fillet who, one afternoon six hundred years ago, had looked so bored until, because of some remark which I could not catch, spoken by a man in another time, she had lifted her head and smiled.

CHAPTER FIVE

THERE WAS AN airmall letter from Vita on my breakfast tray next morning. It was written from her brother's house on Long Island. The heat was terrific, she said, they were in the pool all day, and Joe was taking his family to Newport on the yacht he had chartered mid-week. What a pity we had not known his plans earlier on. I could have flown the boys over and we could all have spent the summer vacation together. As things were, it was too late to change anything. She only hoped the Professor's house would turn out to be a success — and how was it, anyway? Did I want her to bring a lot of food down from London? She was flying from New York on Wednesday, and hoped there would be a letter for her at the flat in London. Today was Wednesday. She was due in at London airport around ten o'clock this evening, and she would not find a letter in the flat because I had not expected her until the weekend.

The thought of Vita arriving in the country within a few hours came as a shock. The days I had thought my own, with complete freedom to plan as I wished, would be upset by telephone calls, demands, questions, the whole paraphernalia of life en famille. Somehow, before the first telephone call came through, I must be ready with a delaying device, some scheme to keep her and the boys in London for at least another few days.

Magnus had suggested drains. Drains it well might be, but the trouble was that when Vita finally arrived she would naturally start asking Mrs. Collins about it, and Mrs. Collins would stare at her in blank surprise. The rooms not ready? This would reflect on Mrs. Collins, and bode ill for future relations between the two women. Electricity failure? But it hadn't any more than the drains. Nor could I pretend to be ill, for this would bring Vita down immediately to move me, wrapped in blankets, to hospital back in London; she was suspicious of all medical treatment unless it was top grade. Well, I must think of something, if only for Magnus's sake; it would be letting him down if the experiment was brought to an abrupt conclusion after only two attempts to prove success. Today was Wednesday. Say experiment on Wednesday, give it a miss on Thursday, then experiment on Friday, a miss on Saturday, experiment on Sunday, and, if Vita was adamant about coming down on Monday, then Monday she must come. This plan allowed for three trips (the L.S.D. phraseology was certainly apt) and, providing nothing went wrong and I chose my moment well, did nothing foolish, the side-effects would be nil, just as they had been yesterday, apart from the sense of exhilaration, which I should immediately recognise and accept as a warning. In any event I felt no exhilaration now; Vita's letter was doubtless the cause of the slight despondency that appeared to be my form today.

Breakfast over, I told Mrs. Collins that my wife was arriving in London tonight, and would probably be coming down with her boys next week, on Monday or Tuesday. She immediately produced a list of groceries and other things which would be needed. This gave me an opportunity to drive down to Par to collect them, and at the same time think out the text of a letter to Vita which she would get the following morning. The first person I saw in the grocer's was the vicar of Saint Andrew's, who crossed the shop to say good morning. I introduced myself, belatedly, as Richard Young, and told him that I had taken his advice and gone to the county library at Saint Austell after leaving the church. "You must be a real enthusiast," he smiled. "Did you find what you wanted?"

"In part," I replied. "The heiress Isolda de Cardinham proved elusive in the book of pedigrees, although I found a descendant, Isolda Carminowe, whose father was a Reynold Ferrers of Bere in Devon."

"Reynold Ferrers rings a bell, he said. The son, I believe I'm right in saying, of Sir William Ferrers who married the heiress. Therefore your Isolda would be their granddaughter. I know the heiress sold the manor of Tywardreath to one of the Champernounes in 1269, just before she married William Ferrers, for one hundred pounds. Quite a sum in those days."

I made a rapid calculation in my head. My Isolda could hardly have been born before 1300. She had not looked more than about twenty-eight at the bishop's reception, which would date that event around 1328. I followed the vicar round the shop as he made his purchases. "Do you still celebrate Martinmas at Tywardreath?" I asked.

"Martinmas?" he echoed, looking bewildered — he was hesitating between a choice of biscuits. "Forgive me, I don't quite follow you. It was a well-known feast in the centuries before the Reformation. We keep Saint Andrew's Day, of course, and generally hold the church fete in the middle of June."

"Sorry," I murmured, "I've got my dates rather mixed. The truth is, I was brought up a Catholic, and went to school at Stonyhurst, and I seem to remember we used to attach a certain importance to Saint Martin's Eve…"

"You are perfectly right," he interrupted, smiling. "November 11th, Armistice Day, has rather taken its place, hasn't it? Or rather, Armistice Sunday. But now I understand your interest in the Priory, if you're a Catholic."

"Non-practising," I admitted, "but you have a point. Old customs cling. Do you ever have a fair on the village green?"

"I'm afraid not," he said, plainly puzzled, "and to the best of my knowledge there has never been a village green at Tywardreath Excuse me…"

He leant forward to receive the purchases dropped in his basket, and the assistant turned his attention to me. I consulted the list given me by Mrs. Collins, and the vicar, with a cheery good morning, went his way. I wondered if he thought me mad, or merely one of Professor Lane's more eccentric friends. I had forgotten Saint Martin's Eve was November 11th. An odd coincidence of dates. Slaughter of oxen, pigs and sheep, and in the world of today a commemoration of uncounted numbers slain in battle. I must remember to tell Magnus. I carried my load of groceries outside, dumped them in the boot of the car, and drove out of Par by the church road to Tywardreath. But instead of parking outside the gents hairdressers, as I had done the day before, I drove slowly up the hill through the centre of the village, trying to reconstruct that non-existent village green. It was hopeless. There were houses to right and left of me, and at the top of the hill the road branched right to Fowey, while to the left the sign-post said To Treesmill. Somewhere, from the top of this hill, the Bishop and his cortege had driven yesterday, and the covered wagonettes of Carminowes, Champernounes and Bodrugans, their coats-of-arms emblazoned on the side. Sir John Carminowe would have taken the right-hand fork — if it existed — to Lostwithiel and his demesne of Bockenod, where his lady awaited her confinement. Today Bockenod was Boconnoc, a vast estate a few miles from Lostwithiel; I had passed one of the lodge gates on my drive down from London. Where, then, did the lord of the manor, Sir Henry de Chainpernoune, have his demesne? His wife Joanna had told her steward, my horseman Roger, 'The Bodrugans lodge with us tonight.' Where would the manor house have stood?

I stopped the car at the top of the hill and looked about me. There was no house of any great size in the village of Tywardreath itself; some of the cottages could be late eighteenth century, but none belonged to an earlier period. Reason told me that manor houses were seldom destroyed, unless by fire, and even if they were burnt to the ground, or the walls crumbled, the site would be put to another purpose within a few years, and a farmhouse erected on the spot to serve the one-time manor lands. Somewhere, within a radius of a mile or two of Priory and church, the Champernounes would have built their own dwelling, or the original manor-house would have awaited them when the first Isolda, the Cardinham heiress, sold them the manor lands in 1269. Somewhere — down that left-hand fork, perhaps, where the sign-post read To Treesmill — the foot-tapping Joanna, impatient to be home, had driven in her painted wagonette from the Priory reception, accompanied by her sad-faced lord Sir Henry, and their son William, and followed by her brother Otto Bodrugan and his wife Margaret.

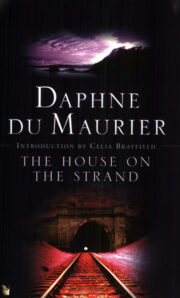

"The House on the Strand" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The House on the Strand". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The House on the Strand" друзьям в соцсетях.