Eleanor was in despair. She conferred with the Archbishop of Rouen. She raved against the injustice done to the man who had done more for Christendom than any other living at the time. He had sacrificed a great deal, he had placed his kingdom in jeopardy for the sake of the Holy War, and what had happened to him, he was imprisoned, not by a Saracen, which would have been understandable, but by those who should have been his friends.

She was desperate. She prayed that God might overlook the wickedness of her youth and not visit her sins on her innocent sons. She spent hours on her knees calling to the virgin. ‘Mother of Mercies, help a miserable mother.’ But she was not of a nature to rely on prayer alone.

First she considered going in search of him; then the possibility of what might happen in her absence if she did deterred her from this action. She must stay here. When he was released there must be a kingdom for him to govern.

But what could she do? Would the Pope help? He could demand Richard’s release immediately if he wished. But why should he go against the wishes of powerful Henry?

She was desperate and uncertain and as she passed one of the rooms she heard the mournful strumming of a lute.

She looked inside to see who was there and saw Blondel de Nesle, one of Richard’s favourite minstrels. He was seated on a stool and as he played a sorrowful dirge the tears ran down his cheeks.

‘What ails you?’ asked Eleanor.

‘My lord’s absence, my lady.’

‘I believe you were a favourite of his. He loved you dearly.’

‘’Twas so, my lady. I would have fain stayed with him and begged to do so, but he wouldn’t have it and sent me here.’

‘Do not weep, pretty boy. He will return.’

When she had left him Blondel continued to weep.

He must return, he said to himself, or I shall die.

Chapter XVII

BLONDEL’S SONG

The frustration which had overwhelmed Richard when he was first brought to the Castle of Dürenstein had given way to resignation. He had endured hardship during his campaigns and had never complained on that score, so that now he found himself a prisoner in an alien land, he could shrug aside any physical inconveniences.

That it should have been Leopold into whose hands he had fallen was indeed galling and that Leopold’s overlord should be the Emperor Henry VI of Germany was a further ironic twist. During the first weeks of his captivity he had asked himself what could possibly happen next; and now it seemed that fate might decide to allow his brother John to succeed in making himself King.

But his resilience had never failed him yet. There was that in him which could overawe those about him. Even when he had faced Leopold and been obliged to hand over his sword the Duke of Austria had quailed before him. He might be a prisoner but he was still Coeur de Lion, the greatest and most renowned soldier in the world. No one could forget that and when they stood before him and he drew himself to his full height and gave them his cold stare their stature seemed to decrease and they trembled. It was amusing. He had no fear of them. That was the secret. That was his great quality. Whatever the situation, Richard was the one who struck fear into his opponent not they into him whatever their advantage.

He had seen that when the Duke of Austria brought him here he was uncertain what should be done with him, and had immediately despatched messengers to his Emperor for instructions because he feared the responsibility of holding King Richard. Poor Leopold, he had always been a braggart and braggarts were notoriously men of straw, crowing like cockerels in a farmyard to call attention to their strength lest it should be suspected that they had none.

So Richard had passed his first weeks in Dürenstein speculating on the possibility of escape. It might seem remote and it was clearly because his captors feared they could not hold him that they had chosen such a spot as Dürenstein. It seemed impregnable with iron bars set across the narrow window which was cut out of the thick stone wall. The natural rock formed part of the castle wall on one side and below were the craggy rocks and the River Danube. Escape that way seemed out of the question. There might be other ways. His custodian Hadamar von Kuenring feared it, and he was a very anxious man. But during his first days in the castle von Kuenring had come to him being most anxious to impress on him that he was well aware that the King was a very special prisoner and he had no desire to show disrespect; indeed he was eager to do everything possible – providing he did not go against the wishes of his master Leopold – to make Richard’s stay at Dürenstein comfortable.

‘Such a situation as that in which I find myself could scarcely be expected to bring me comfort,’ said Richard. ‘If you can do that you are possessed of supernatural powers.’

Richard smiled wryly as he spoke but there was little humour in this officer of Leopold’s guard. He went on: ‘Your page who betrayed you is here in the castle. I will send him to you that he may serve you. We hold another of your men, William de l’Estang, and I shall put nothing in the way of your enjoying the companionship of your friend.’

This was indeed good news. William de l’Estang was a man Richard had always liked and his company would be very welcome.

His young page was brought to his cell and fell on his knees before the King who raised him up and embraced him.

‘My lord, Sire,’ cried the boy and began to weep.

Richard stroked his hair. ‘I understand, little one. The cruel men threatened you.’

‘To tear out my tongue and to put out my eyes.’

‘And would have done it too, God curse them. All is well. Have no fear now.’

‘But, my lord, I led them to you.’

‘Nay, they would have found me. Dry your tears. Serve me well and it shall be as it ever was.’

The boy fell once more on to his knees and kissed Richard’s feet.

It was pleasant to have him.

The days began to pass. Richard was allowed to walk out on to the ramparts as long as he was surrounded by guards. William de l’Estang came and spent the hours of daylight with him; they played chess together and sometimes von Kuenring would play against one of them while the other looked on. Von Kuenring gave Richard a lute and while they played chess the page would play softly. Richard himself often played it and the three of them would sing together.

Richard’s voice which was powerful could often be heard in the castle and it was marvelled that one who was a captive could so forget his woes in such songs, many of which were gay.

In fact they marvelled at Richard who did not seem to resent his captors. He liked to test his physical strength with his guards in the courtyard where he would wrestle with them much to the amusement of the onlookers. He selected the tallest and strongest looking men for his opponents and the rest of the guards would watch in amazement, for invariably Richard proved himself the stronger.

Then he would go to his cell and play chess or sing. He was composing a sirvente of seven stanzas which he said would tell the world – if it ever heard it – how he felt about his prison.

Sometimes he would talk to William de l’Estang of escape. Was it possible? Could they scale those rocky walls? The guards were ever watchful. Every night special men came to his cell. They were the biggest and most powerful soldiers in the Duke’s army, and that was why they had been chosen to guard Richard. They placed themselves about his bed and through the night sat there, their great swords at their sides.

‘If we were to escape,’ said de l’Estang, ‘where should we go? We should be discovered in a short time and put in an even stronger fortress.’

Richard agreed.

‘If we could but get a message to my mother ...’

‘But how? We are watched day and night.’

‘I know not,’ said Richard. ‘But help must come from somewhere.’

When he was most desperate he turned to his music. It comforted him more than anything.

He sang the first verses of his sirvente to William. Poignantly it expressed the plaintive lament of the prisoner.

‘It is a little like a song I composed with Blondel de Nesle some time ago. Do you remember Blondel, William?’

‘I do, Sire. A handsome boy and devoted to you.’

‘He wished to come with me. If I had allowed him to he might well be here with me now. I wondered whether he would have lost his eyes or his tongue for my sake. I would not have had it so. Our poor little page lives in perpetual remorse. Comfort him, William. Make sure he knows that I understand.’

‘You yourself with your usual generosity have conveyed it, Sire.’

‘I hope Blondel reached England safely. He is a good boy and a fine minstrel.’

‘I doubt your brother will appreciate that.’

‘Let us hope so, William. Send for the page. Let him sing for us. You and I will go to the chess board and get a game while daylight lasts.’

The news was spreading through Europe. Richard a prisoner and none knew where. But there was a firm belief that he was in the hands of Leopold of Austria and that meant that Henry of Germany would have jurisdiction over him.

John was gleeful. The news couldn’t have been better. He chuckled over it with Hugh Nunant. Philip of France was sending secret messages to him. Nothing could have suited them better. Philip was amused. He remembered the altercation between Richard and Leopold on the walls of Acre. Was Richard regretting his hasty action now? No, the answer must be. Richard would remain aloof and dignified implying that he would do it again even if he had pre-knowledge that later he would be the Duke’s prisoner. There was something fine about Richard. Would to God, thought Philip, that he were my prisoner.

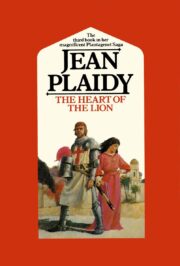

"The Heart of the Lion" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Heart of the Lion". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Heart of the Lion" друзьям в соцсетях.