He stood still, his arm across the window, and had just begun to say, “I can see something through the trees which might be — ” when there was a loud report, and he sprang aside, clutching his forearm, which felt as though a red-hot wire had seared it. For a moment, his senses were entirely bewildered by the shock; then he became aware that his sleeve was singed and rent, that blood was welling up between his fingers, and that Sophy was laying down an elegant little pistol.

She was looking a trifle pale, but she smiled reassuringly at him, and said, as she came toward him: “I do beg your pardon! An infamous thing to have done, but I thought it would very likely make it worse for you if I warned you!”

“Sophy, have you run mad?” he demanded furiously, beginning to twist his handkerchief round his arm. “What the devil do you mean by it?”

“Come into one of the bedchambers, and let me bind it up. I have everything ready. I was afraid you might be a little cross, for I am sure it must have hurt you abominably. It took the greatest resolution to make me do it,” she said, gently propelling him toward the door.

“But why? In God’s name, what have I done that you must needs put a bullet through me?”

“Oh, nothing in the world! That door, if you please, and take off your coat. My dread was that my aim might falter, and I should break your arm, but I am sure I have not, have I?”

“No, of course you have not! It is hardly more than a graze, but I still don’t perceive why — ”

She helped him to take off his coat, and to roll up his sleeve. “No, it is only a slight flesh wound. I am so thankful!”

“So am I!” said his lordship grimly. “I may think myself fortunate not to be dead, I suppose!”

She laughed. “What nonsense! At that range? However, I do think Sir Horace would have been proud of me, for my aim was as steady as though I were shooting at a wafer, and it would not have been wonderful, you know, if my hand had trembled. Sit down, so that I may bathe it!”

He obeyed, holding his arm over the bowl of water she had so thoughtfully provided. He had a very lively sense of humor, and now that the first shock was over, he could not prevent his lip quivering. “Yes, indeed!” he retorted. “One can readily imagine a parent’s pleasure at such an exploit! Resolution is scarcely the word for it, Sophy! Don’t you even mean to fall into a swoon at the sight of the blood?”

She looked quickly up from her task of sponging the wound. “Good God, no! I am not missish, you know!”

At that he flung back his head and broke into a shout of laughter. “No, no, Sophy! You’re not missish!” he gasped, when he could speak at all. “The Grand Sophy!”

“I wish you will keep still!” she said severely, patting his arm with a soft cloth. “See, it is scarcely bleeding now! I will dust it with basilicum powder, and bind it up for you, and you may be comfortable again.”

“I am not in the least comfortable and shall very likely be in a high fever presently. Why did you do it, Sophy?”

“Well,” she said, quite seriously, “Mr. Wychbold said that Charles would either call you out for this escapade, or knock you down, and I don’t at all wish anything of that nature to befall you.”

This effectually put a period to his amusement. Grasping her wrist with his sound hand, he exclaimed, “Is this true? By God, I have a very good mind to box your ears! Do you imagine that I am afraid of Charles Rivenhall?”

“No, I daresay you are not, but only conceive how shocking it would be if Charles perhaps killed you, all through my fault!”

“Nonsense!” he said angrily. “As if either of us were crazy enough to let it come to that, which, I assure you, we are not — ”

“No, I feel you are right, but also I think Mr. Wychbold was right in thinking that Charles would — what does he call it? — plant you a facer?”

“Very likely, but although I may be no match for Rivenhall, I might still give quite a tolerable account of myself!”

She began to wind a length of lint round his forearm. “It could not answer,” she said. “If you were to floor Charles, Cecy would not like it above half; and if you imagine, my dear Charlbury, that a black eye and a bleeding nose will help your cause with her, you must be a great gaby!”

“I thought,” he said sarcastically, “that she was to be made to pity me?”

“Exactly so! And that is the circumstance which decided me to shoot you!” said Sophy triumphantly.

Again, he was quite unable to help laughing. But the next moment he was testily pointing out to her that she had made so thick a bandage round his arm as to prevent his being able to drag the sleeve of his coat over it.

“Well, the sleeve is quite spoilt, so it is of no consequence,” said Sophy. “You may button the coat across your chest, and I will fashion you a sling for your arm. To be sure, it is only a flesh wound, but it will very likely start to bleed again, if you do not hold your arm up. Let us go downstairs, and see whether Mathilda has yet made tea for us!”

Not only had the harassed Mrs. Clavering done so, but she had sent the gardener’s boy running off to the village to summon to her assistance a stout, red-cheeked damsel, whom she proudly presented to Sophy as her sister’s eldest.

The damsel bobbing a curtsy, disclosed that her name was Clementina. Sophy, feeling that Lacy Manor might be required to house several persons that night, directed her to collect blankets and sheets, and to set them to air before the kitchen fire. Mrs. Clavering, still toiling to make the breakfast parlor habitable, had set the tea tray in the hall, where the fire had begun to bum more steadily. From time to time puffs of smoke still gushed into the room, but Lord Charlbury, pressed into a deep chair, and given a cushion for the support of his injured arm, felt that it would have been churlish to have animadverted upon this circumstance.

The tea, which seemed to have lost a little of its fragrance through its long sojourn in the pantry cupboard, was accompanied by some slices of bread and butter and a large, and rather heavy plum cake, of which Sophy partook heartily. Outside, the rain fell heavily, and the sky became so leaden that very little light penetrated into the low-pitched rooms of the manor. A stringent search failed to discover any other candles than’ tallow ones, but Mrs. Clavering soon brought a lamp into the hall, which, as soon as she had drawn the curtains across the windows, made the apartment seem excessively cozy, Sophy informed Lord Charlbury.

It was not long before their ears were assailed by the sound of an arrival. Sophy jumped up at once. “Sancia!” she said, and cast her guest a saucy smile. “Now you may be easy!” She picked up the lamp from the table and carried it to the door, which she set wide, standing on the threshold with the lamp held high to cast its light as far as possible. Through the driving rain she perceived the Marquesa’s barouche-landau drawn up by the porch, and as she watched, Sir Vincent Talgarth sprang out of the carriage and turned to hand down the Marquesa. In another instant, Mr. Fawnhope had also alighted and stood transfixed, gazing at the figure in the doorway, while the rain beat unheeded upon his uncovered head.

“Oh, Sophie, why?” wailed the Marquesa, gaining the shelter of the porch. “This rain! My dinner! It is too bad of you!”

Sophy, paying no heed to her plaints, addressed herself fiercely to Sir Vincent, “Now, what the deuce does this mean? Why have you accompanied Sancia, and why the devil have you brought Augustus Fawnhope?”

He was shaken by gentle laughter. “My dear Juno, do let me come in out of the wet! Surely your own experience of Fawnhope must have taught you that one does not bring him; he comes! He was reading the first two acts of his tragedy to Sancia when your messenger arrived. Until the light failed, he continued to do so during the drive.” He raised his voice calling, “Come into the house, rapt poet! You will be soaked if you stand there any longer!”

Mr. Fawnhope started, and moved forward.

“Oh, well!” said Sophy, making the best of things, “I suppose he must come in, but it is the greatest mischance!”

“It is you!” announced Mr. Fawnhope, staring at her. “For a moment, as you stood there, the lamp held above your head, I thought I beheld a goddess! A goddess, or a vestal virgin!”

“Well, if I were you,” interposed Sir Vincent practically, “I would come in out of the rain while you make up your mind.”

Chapter 17

LADY OMBERSLEY and her daughters, driving soberly home from Richmond in the late afternoon, reached Berkeley Square to find Miss Wraxton awaiting their return. After affectionately embracing Lady Ombersley, she explained that she had ventured to sit down to wait for her, since she was the bearer of a message from her mama. Lady Ombersley, feeling a little anxious about Amabel, who was looking tired and had complained of a slight headache on the way home, answered absently, “Thank your mama so much, my dear. Amabel, come up to my dressing room, and I will bathe your forehead with vinegar! You will be better directly, my love!”

“Poor little dear!” said Miss Wraxton. “She looks sadly peaked still! You must know, ma’am, that we have put off our black gloves. Mama is desirous of holding a dress party in honor of the approaching event — quite a small affair, for so many people of consequence are out of town! But she would not for the world fix upon a day that will not suit your arrangements. You behold in me her envoy!”

“So kind of her!” murmured her ladyship. “We shall be most happy — any day that your mother likes to appoint. We have very few engagements at present! Excuse me, I must not stay! Amabel is not quite well yet, you know! Cecilia will arrange it with you. Say everything from me to your mama which is proper! Come, dearest!”

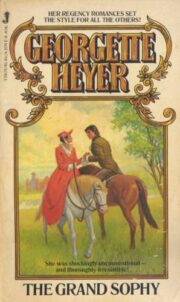

"The Grand Sophy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Grand Sophy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Grand Sophy" друзьям в соцсетях.