Not long after Robert had secured his place in politics, the supposedly good Christian politican developed a wandering eye, or maybe just gave in to it. Naturally, she had been the last to hear the whispers. But what she definitely hadn’t heard until after the divorce papers were set in front of her was that the real reason he needed a divorce was because he had gotten one of his aides pregnant.

When the surprisingly quick divorce came through, she had fled Texas in a storm of devastation and betrayal, finding herself shipwrecked on the island of Manhattan, with nothing more than the two hastily packed suitcases and her grandmother’s cherished Glass Kitchen cookbooks—thrown in even though she didn’t want them.

Rolling back over, she tossed the pillow aside. She had arrived in New York City a month ago, but she had been in Great-aunt Evie’s town house only since late last night, using an old key she had kept on her key chain. Before Evie had died, she had divided the town house up into three apartments, two of which she had rented out for income. Upon her death, one apartment had gone to each of the sisters.

Cordelia and Olivia had sold their floors. Before the divorce, Robert had wanted to sell her floor, too, with the garden out back, but she had never signed the contract. Thank God. While she was having a hard time imagining herself living in New York City, she wasn’t crazy. Staying in Texas, where Robert and his pregnant new wife had already started to rule her world, was an awful thought. Here in New York, she had something of her own. Everything was going as well as could be expected, given that her bank account was nearly as bare as Great-aunt Evie’s kitchen cupboards.

The early morning air in New York was far cooler than it would have been in Texas, especially in the ancient bathroom, where the windows barely shut out the chilly gusts. Portia braced her hands on the old-fashioned sink, looked at herself in the mirror. Her eyes were still a deep violet blue, but the circles beneath them hinted at the stress that kept her awake at night. A year ago, she’d had sensibly cut, shoulder-length blond hair—perfect for a Texas politician’s wife—tamed by a blow-dryer, hair spray, and a velvet headband. She scoffed. She’d been a cliché of big hair, sure, but what was she now? An even bigger cliché of the wronged wife kicked out of her own bed by her husband and the ex–best friend whom she herself had convinced Robert to hire as an aide. As her life spiraled out of control, so had her hair, growing and curling as it had when she was a child.

She turned on the old-fashioned spigot, the pipes clanging before spitting out a gush of water that she splashed on her face. Then she froze when her head filled with images of cake, thick swirls of buttercream frosting between chocolate layers. Her breath caught, her fingers curling around the sink edge. It had been three whole years since she’d been hit by images of food. But she knew the images were real—or would be if she allowed the knowing to take over.

She shook her head hard. She was normal now. The knowing was in the past. She hadn’t done so much as toast a slice of bread in the last three years.

But the feeling wouldn’t leave her alone, and with a groan she realized that the knowing was back, as if her move to New York, to this town house, had chiseled away every inch of normalcy she had cobbled together.

The images swirled through her. She needed to bake. Cake. A layered chocolate cake. With vanilla buttercream frosting.

The images were as clear as four-color photos from a coffee table book on baking. She could taste the mix of vanilla, butter, and cream whipped into a sugar frosting as if she had spooned it into her mouth. The chocolate smelled so real that a chill of awareness ran along her skin, pooling in her fingertips. She itched to bake.

But the last thing she needed in her life right now was to contend with something else she couldn’t control.

She fought harder, but another bit of knowing hit. It wasn’t just baking. She needed to cook, too. A roast.

She pressed one of her great-aunt’s threadbare white towels to her face, resisting the urge. She had devoted the last three years to being the perfect wife. She had let her grandmother’s Glass Kitchen go, closing the doors for good and selling the property for next to nothing to a developer who only wanted the land, splitting the money with her sisters. Her job had been to be at her husband’s side at any function. Given that she had signed a prenuptial agreement, and with the meager settlement Robert had yet to pay her, she barely had two pennies to rub together. The last thing she needed to do was to waste money preparing a big meal. But the need wouldn’t let go, and with a shudder gasp she gave in completely, the last of her crumbling walls coming down. Flowers, she realized. She needed flowers, too.

The knowing was rusty, coming at her in fits and starts, much like the water sluicing unevenly out of the faucet. Groaning, Portia dressed in jeans instead of a conservative skirt, and a big sweater instead of a silk blouse. She found flowered Keds in her great-aunt’s closet, which she dusted off to wear rather than sensible heels. She wasn’t Mrs. Robert Baleau anymore. She was Portia Cuthcart again, having taken back her maiden name.

The goal, her grandmother always said in the few times she actually said anything about the knowing, was to give in to the simple act of doing and have faith that eventually everything would make sense.

“Great,” Portia muttered.

Once dressed, she went to her still-packed suitcases. A tiny bead of sweat broke out on her forehead when her fingers brushed against the spine of a Glass Kitchen cookbook. The handmade books had been passed down just as the knowing had, though just as with lessons on the knowing, Gram had never shared the books, either. Portia never knew they existed until after her grandmother’s death.

Now she cracked the spine on the first of three volumes, her pulse beating in her temples. She recognized Gram’s writing, notes scribbled between the crudely typed lines, new details learned and added, old ingredients scratched out. She turned the pages, her breath high in her chest, short bursts. Each generation of Cuthcart women had written in the margins, filling in newly learned wisdom along with the recipes. But even the recipes held gems of magic.

For perfectly boiled water, let it jump with enthusiasm, but not so energetically that it becomes exhausted, tiring the food it will boil.

And:

Never prepare a meal in anger, for the end result will fill the recipients with bile.

An hour later, when she came to the end of the volume, Portia jerked up, the book falling to the ground. Enough!

She scrambled out of the apartment, the cool morning air hitting her like a gasp of relief. With the Keds dangling in her fingers, she just stood there for a second, breathing, in, out, before she finally sat down to pull on the flowered sneakers.

She had just finished tying the last shoelace when she saw him.

He was tall, lean, with broad shoulders, dark brown hair. He looked primal, with a firm jaw and hard brow, walking toward her with a fluidity that seemed physically impossible, given his size. He had none of Robert’s pretty-boy good looks, and there didn’t seem to be anything practiced or politically correct about him. From the look of him, she imagined he was one of those New York businessmen she had heard about who traded stocks like third-world countries trade rulers, easily and ruthlessly.

Of course he wasn’t dressed like a businessman. He wore a black T-shirt, long athletic shorts, and sweat-slicked hair. He had the smooth, tight muscles of someone who was athletic but didn’t spend his days as an athlete. It wasn’t hard to imagine him showering and then heading out of this tree-lined neighborhood on his way to some glass-and-steel office building in the concrete jungle of Midtown Manhattan.

She knew the minute he saw her, the way his eyes narrowed as if trying to understand something. She felt the same thing, as if she knew him, or should.

Images of food rushed through her head, surprising her. Fried chicken. Sweet jalapeño mustard. Mashed potatoes. Biscuits. And a pie. Big and sweet, strawberries with whipped cream—so Texan, so opposite this fierce New Yorker.

Good news or bad? she wondered before she could stop herself.

“No, no, no,” she whispered. The images of food meant nothing at all. She wanted nothing to do with him, with any guy, at this point in her life. And she definitely didn’t want anything to do with the kind she felt certain wielded power like a club. Robert charmed his way into control, but she knew on sight that this man would take it by force.

When he reached the steps, he stopped, looking at her with an intensity that felt both assessing and oddly possessive. It might have been an hour, or a second; no smile, no awkwardness, and her breathing settled low. She became acutely aware of herself, and him. Everything about this man pulled her in, which was ridiculous. He could be a serial killer. He could be demented, insane. With a body like that, he probably didn’t eat sugar. A deal killer, for sure.

His head cocked to the side. “Do I know you?”

Portia smiled—she was Texan, after all, and had learned manners at a young age, even if it was out of a library book her mother “accidentally” forgot to return—and his expression turned to something deeper, richer like a salted hot fudge.

“No,” she answered, the word nearly sticking in her throat. “Should you?”

Desire had caused the storm that left her shipwrecked in Manhattan—the desire her husband felt for another woman. But there had been her own desire, too, the desire for intensity and excitement in her own life, which she had suppressed when she married Robert. Sitting there, she felt that desire stir inside her like the first bubble rising in a pot of caramelizing sugar.

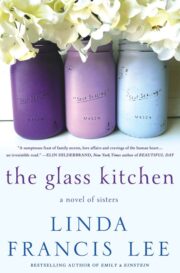

"The Glass Kitchen: A Novel of Sisters" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Glass Kitchen: A Novel of Sisters". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Glass Kitchen: A Novel of Sisters" друзьям в соцсетях.