Augustus didn’t take the bait. “That’s not the point. The point is that you lied for me.”

That was a poet for you, parsing every word. Emma glowered at him. “It would have put a damper on the performance if we had had to pause to guillotine you.”

“Emma.” He planted his hands on the doorframe to either side of her. They were in trouble, thought Emma vaguely, should someone try to come out. She was pinned to the door like someone’s archery target. “Emma, I have something to tell you.”

He looked so earnest. But hadn’t she seen that before? He did earnest quite well. “What might it be this time? Do you have nine wives in the attic? A taste for women’s undergarments?” Emma made to duck under his arm. “Forgive me if I have very little interest in hearing.”

Augustus blocked her by the simple expedient of lowering his arm. Trapped. She was trapped. “Emma, Mr. Fulton is coming back to England with me.”

Emma stopped wiggling. “What?”

Augustus dropped his arms. “I spoke to him a few moments ago. He’s not happy with the reception of his submarine. He believes it would fare better in England.”

Emma slowly assimilated the new information. “So you’re not only stealing the plans, you’re stealing the man.”

“Hardly stealing when he comes willingly,” said Augustus reasonably. Why did he have to be reasonable? Emma was feeling anything but. He had this all turned around, so that, somehow, he was in the right. It made no sense. “There’s something else.”

“Are you taking cousin Robert, too?” asked Emma crankily. “Perhaps England could use a lightly used envoy.”

“Now you’re being silly.” She was being silly? Emma would have expressed her indignation had she the breath to do so—and if Augustus hadn’t surprised her by suddenly making a grab at her hands. “Come with me, Emma. Come to England with me.”

Emma wasn’t quite sure she had heard him right. “England? Me?”

Augustus looked at her tenderly. “England. You.”

No. This wasn’t right. Not any of it. Emma snatched her hands away, her mind a muddle of plans and deceptions and unlikely seductions.

“Why? So I won’t reveal your secret?”

Augustus didn’t seem offended or alarmed by the question. He shook his head. “As soon as I leave France with Mr. Fulton, my identity is already compromised. I’m not coming back to France, Emma. This is it for me. I’m going back to England and starting over. Just as you said I should.” He looked down at her, his eyes locking with hers. “But I can’t do it without you.”

Emma cleared her throat as best she could. “I don’t understand.”

“Yes, you do,” said Augustus. She could feel the panels of the door hard against her back, blocking her egress. “You just don’t want to. And I can’t blame you for it. I understand why you’re angry with me. If circumstances were different, I could make it up to you in a million different ways. I could woo you slowly, token by token. I could find ways to make you trust me again, hour by hour and day by day. But we don’t have that kind of time.”

Emma said the only thing she could think of to say. “When do you leave?”

“As soon as I make the arrangements. Three days at the outside. Fewer, if anything goes wrong.”

“That soon.” It wasn’t enough time. She needed time to think, to make sense of it all.

Augustus’s hands settled on her shoulders, massaging the tense muscles at the base of her neck. “Come with me, Emma.”

Come live with me and be my love / And we shall all the pleasures prove. They had discussed that poem together, a very long time ago, all the shepherd’s seductive promises to his love.

“There’ll be a reward for this,” Augustus was saying. “Not a large one, but enough to set up that journal I’ve always wanted, maybe make a run for Parliament. There’ll be no more deceptions, no subterfuge, no playacting.” He looked down with a rueful grin. “No more shirts like these.”

He looked so much younger when he smiled like that. So much younger and more carefree, as though he were already sloughing off the weight of carting around a second identity, so much more wearing than a waistcoat.

Emma’s throat was tight. “And will you make me beds of roses and a thousand fragrant posies?”

Augustus’s expression softened. “A cap of flowers and a kirtle, embroidered all with fragrant myrtle, and silver dishes for thy meat, as fragrant as the gods do eat. Well, maybe not that,” he amended. “English cuisine isn’t known for its Lucullan qualities. But the flowers are lovely in the meadows in springtime, as lovely as the poet claims. I’ll make you crowns of daisy chains and beds of violets.”

“What about the frosts?” asked Emma. “It can’t be always summer.”

“Even better,” said Augustus. “There’ll be sleighing and skating and hot chocolate on cold days, with the steam rising to make patterns in the cold air. We can go down to the Thames and watch the apprentices skid on the frozen river or go out to the countryside and cut holly for the color of the berries. Or we can stay warm inside, with no place better to be than with each other. Outside, the winds will batter and blow, but we’ll have long nights in front of the fire, as the sparks fly and crackle, and crisp mornings buried beneath the quilts.”

Emma could picture it, their own little refuge against a cold world, with firelight brightening the windows against the winter dusk. A sofa—not a spindly, narrow French construction, but something comfortable and deep—and a good fire in a proper hearth, sending slicks of warm light pooling along the surfaces of the furniture and reflecting off the panes off the windows. The winds would batter, but inside they would warm, curled up together on the couch, his papers on one side, her books on the other.

It wasn’t the shepherd’s promise of endless summer or Americanus’s pledge of boundless plenty. But Emma found it all the more seductive for all that.

“A new life in an old world,” said Emma, testing the concept.

“It’s a new life for me, too,” said Augustus. “It’s been a good decade since I’ve been back. We’ll learn it together, the two of us, our own demi-paradise.”

He was switching poets on her, from Marlowe to Shakespeare. But it wasn’t either of them who spoke to Emma. It was another one of those Elizabeth courtiers, whichever of them it was who had written the nymph’s reply to the shepherd.

If all the world and love were young and truth on every shepherd’s tongue, these pretty pleasures might me move to live with thee and be thy love.…

If. It was a horrible and powerful if. She had felt that way nine years ago, with Paul, when the world and love were young, and look how wrong she’d got it then. The first hint of frost, and all his pretty flowers, all his vows and protestations had withered, and her love along with them. She was older now, and hardier, and there was no telling whether this might not be a sturdier plant, a tree rather than a shrub, but how could she possibly know? Especially with so little time?

No matter how honorable Augustus’s intentions might be at this particular moment, there were no guarantees.

It had hurt enough last time, watching love crumble to dust, picking up the pieces of her life and trying to go on, and that had been with the love and support of her old schoolfellows. She wasn’t sure she could do it again.

No matter how tempting.

“I…can’t,” Emma said, and watched Augustus’s face fall.

“Can’t?” he said carefully. “Or won’t?”

“What difference does it make?” asked Emma despairingly. “Can’t, won’t. I am willing to believe”—Emma glanced down at his waistcoat, fighting with the words—“that you might actually care for me. That you might even think you love me.” She hurried on before he could interject. “But how can I know? What if this is only another matter of policy, too deep for me to understand?”

Augustus tucked a stray lock of hair behind her ear. “What policy would be served by taking you with me?”

“That’s just the problem,” said Emma. “I don’t know. I know nothing of this whole world of yours. I can’t imagine the rules by which you play, or the goals for which you scheme. It’s all foreign to me. Until yesterday, I had no idea any of this even existed. It’s all unfathomable.”

“You don’t have to fathom it,” said Augustus determinedly. “I’m getting out. There’ll be no more of this. No more lies. We’ll even make peace with my father. He’s a clergyman, you know. You can’t get much more straight and narrow than that.”

“So you say,” said Emma. “But how do I know what’s truth and what’s lies? How do I know even that?”

“Those are strong words,” he said slowly.

Emma tilted her head up to him. Tears blurred her vision, presenting him to her as through a glass darkly, the outlines and details vague and uncertain. “What you ask of me is no small thing.”

“Trust,” he said.

Emma nodded wordlessly. She didn’t need to enumerate his deceptions. They stood between them like a palpable thing.

“I have never,” he said, his voice low, “lied to you in anything to do with you. Nor about how I feel for you. The pretext might have been a lie, but the substance never was.”

“Say I believe you,” she said, and her voice wobbled. She forced herself to rush onward before she lost her ability to speak entirely. “Say I believe that you mean it, that you believe it to be true, what if you wake up two months from now to find you mistook your feelings? It’s happened before.”

With Jane. She didn’t say it and neither did he. She didn’t need to. He knew exactly what she meant.

“It is,” she said, “a great deal you ask of me.”

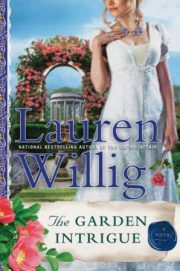

"The Garden Intrigue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Garden Intrigue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Garden Intrigue" друзьям в соцсетях.