Emma wasn’t sure when the balance had shifted; she had been preoccupied with her own affairs, with Carmagnac and Paul and her own wounded feelings. It had been a blurry and confused time, and, at the end of it, she had come to Malmaison to find that the world had shifted, that it was Mme. Bonaparte begging her husband’s affection, biting her lip and looking the other way as he chose his mistresses from among the actresses at the Comédie-Française, and sometimes even from among his stepdaughter’s friends.

Once, Mme. Bonaparte might have had her own way with a single, softly spoken word. Not anymore.

Emma had a very bad feeling about this.

“What can you do?” Emma asked her friend.

Hortense looked down at her son’s head. “I’ve done everything I can do,” she said, and there was a touch of bitterness in her voice. “What else, I don’t know.”

They sat together in silence, each caught in her own thoughts. The sun shone brightly on the river, but it seemed dim to Emma’s eyes, too much light turned dark, like a black spot on one’s eye from staring directly at the sun.

Emma looked at Hortense’s familiar face, at the new hollows between her cheekbones and the shadows below her eyes, prettier, in some ways, than she had been as a girl, but so much sadder. They had sat so often like this, she and Hortense, in this same spot, watching the play of light on the water, tossing crumbs to the ducks, and talking of books and dresses and life and love. Here Emma had told Hortense of her disillusionment with Paul, twisting her hands in her lap, hour slipping into hour as the sun set over the water, and here Hortense had confessed her love for a young general, Duroc, one of the set that had flocked to Malmaison in those long-ago halcyon days.

Hortense had been so certain her stepfather would give his consent.

Emma jerked around as a sudden clatter erupted from the river. Bored with the adults, Caroline’s child had wiggled free and was pelting Mr. Fulton’s steamship with pebbles. The noise battered against Emma’s skull, shattering the illusion of peace. The ducks squawked in protest, their feathers ruffled.

Plink, plink, plink went Achille’s pebbles against the side of Mr. Fulton’s ship. Crowing to himself, he scrambled along the bank, looking for more powerful ammunition. Something, Emma thought bitterly, of which Achille’s uncle Napoleon would approve.

Emma’s hands balled into fists in her lap. “It didn’t need to come to this,” she said.

She didn’t need to explain what she meant; Hortense always knew.

The Emperor’s daughter smiled wryly. “Didn’t it? My stepfather is the comet and we are the tail. We must follow where he leads for better or ill.” Her smile twisted, like a theatrical mask, half comedy, half tragedy. “I imagine the comet’s tail doesn’t much enjoy it either.”

Emma’s heart ached for her friend. She held out a hand. “Hortense—”

Hortense waved her away. “Forgive me. I can’t think why I’m being so melodramatic! It must be the child. It wreaks havoc with one’s emotions. You’ll see.”

“But you’re not being melodramatic. Not at all! Not if you really believe—” Emma would have pressed the topic, but her words were drowned out by a resounding crash.

In the shocked silence that followed, she could hear an ominous cracking noise.

As the crowd stared in mingled horror and delight, the chimney of Mr. Fulton’s steamship cracked, sliding slowly sideways. The ship skewed sideways, a sad, ruined thing.

“I sank it! I sank it!” crowed Achille.

Mr. Fulton looked ill. Kort gaped, as though he couldn’t quite believe what had just happened. Hortense sighed, and shifted her own sleeping son on her lap.

“Yes, you did,” said the Emperor genially. He pushed out of his chair, gesturing brusquely to his staff. “Enough entertainment. To work!” He jerked his head in the direction of Mr. Fulton. “You, too.”

With one last, wordless look of dislike at Achille, Fulton joined the stream of naval commanders following the Emperor to the summerhouse he employed as an office in good weather.

The party was over, at least for some. Emma could see Mme. Bonaparte moving graciously through the crowd, smoothing over her husband’s gaffe, urging everyone to stay where they were and enjoy the refreshments and the fine weather. Most people didn’t need to be asked twice. Someone began plucking at a guitar, singing in a pleasant tenor voice about flowers blooming, bloomed too soon, ducking and striking a false chord as a candied chestnut sailed past one ear. In Hortense’s lap, Louis-Charles stirred fitfully.

“I should take him in,” Hortense said, just as a shadow fell over their sunny spot.

Emma didn’t need to look up. She could see the silhouette stretched across the blanket, the full sleeves, the curling hair, the long legs, distorted and caricatured by the angle of the sun, and, yet, still recognizable. Or maybe it was the other things that she recognized: the smell of fresh-washed linen and ink, the elaborate clearing of the throat that preceded a grand oration.

Augustus addressed himself to Hortense. “Might I beg your indulgence, O Our Madonna of these Riparian Banks?”

“You may,” Hortense said graciously. “Provided that you never call me that again.”

Augustus bowed with a flourish, his head nearly scraping grass. “My dear lady, your lightest wish is my commandment. I crave only the counsel of your companion, should you be so very good as to release her into my custody for a brief colloquy.”

“Her custody is her own,” said Hortense. “Emma?”

Emma looked up at Augustus. “I need to talk to you,” he said in a low voice, intended for her ears alone.

“What is it?” she mouthed, but he only shook his head.

“Are you sure you don’t mind?” Emma asked Hortense.

Hortense mustered something akin to a smile. “Go,” she said. “I’m quite content to doze by the river now that the excitement appears to be over.”

Was it? Emma’s pulse picked up as Augustus held out a hand to Emma. Against her better judgment, she took it, letting him draw her up off the blanket.

“A thousand thanks, O benevolent ladies.” As he waved an enthusiastic farewell to the Emperor’s stepdaughter, Augustus bent close to Emma’s ear, sending a shiver down her spine as he murmured, “Come with me. We need to be private.”

Chapter 24

Hold not a mirror to my heart;

The truth’s a very poisoned dart.

That same mote that you claim to spy,

Becomes a beam in thine own eye.

“Private?” Emma echoed.

Behind her, on the blanket, Hortense studiously pretended not to listen. She was not listening so hard, Emma could practically hear it.

Emma scowled at Augustus. “Surely, whatever it is, you can tell me here.”

“There are some things one prefers to discuss without an audience,” Augustus said circumspectly.

That was certainly informative.

“You plan to abandon poetry and set up as a mantua maker,” Emma extrapolated extravagantly. “No, no, wait, don’t tell me. You have a sudden desire to go prospecting for gold in the outer Antipodes, accompanied only by your faithful bearer, Calvin.”

“Calvin?” If she had hoped to annoy Augustus into an admission, the strategy failed. Her companion conducted a leisurely survey of the grounds, his gaze moving impartially over the revelers, some lounging on blankets, others, less daunted by the warmth of the sun, playing an impromptu game of tag.

“What would you prefer?” Emma grumbled. “Hobbes?”

“Solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short?” Augustus raised a brow. “Why not? We have a fine exhibition of the state of nature here before us.”

One of Mme. Bonaparte’s younger ladies stumbled on the hem of her skirt, tumbling into the grasp of the gallant who had been chasing her. She squeaked as he squeezed her, and dealt him a resounding slap.

Oh. Emma grimaced. Maybe that hadn’t been tag.

“Hardly poor,” she said. There were enough jewels in evidence to fund a small revolution. “Or solitary.”

“You didn’t say anything about brutish.” Augustus regarded the assemblage with a jaded eye. “This lot won’t go in until the food runs out. We’ll have no privacy back here.”

As if in illustration, the guitar struck up again, discordantly. Oh, dear, Lieutenant Caradotte had gotten hold of it. He would insist on playing, despite being tone-deaf. Emma winced as he struck a chord that sounded like an offended feline on a bad day. There was a thud and a squawk as someone tried to wrestle the guitar away.

“Madame Delagardie!” Someone came jogging up. It was another of Bonaparte’s aides—no, not an aide anymore, but he had been three years ago during one of their endless summers at Malmaison. He was something important now, but Emma couldn’t remember what. To her, he would always be the aide whose pantaloons had split during a game of prisoner’s base. Sans Culottes, they had called him for weeks. “Come join us for blindman’s buff!”

Emma waved back, all too aware of Augustus’s hand on her other elbow. Privacy, he had said. Privacy for what? They had agreed there was nothing to talk about. It might be nothing more sinister than plans for the masque, an addendum to the script, a change of cast. There were a hundred and one innocent reasons he might want to speak to her.

“Later,” she called back to Sans Culottes. What was his name? “It’s too warm.”

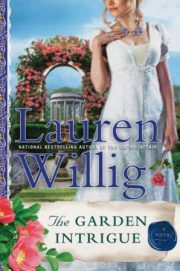

"The Garden Intrigue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Garden Intrigue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Garden Intrigue" друзьям в соцсетях.