What solace from my own weak mind?

“Madame Bonaparte!” Emma dropped into a curtsy. The door swung shut behind her as she released it, banging her in the backside. “I hadn’t thought you were to be here until tomorrow.”

A dozen or so sets of eyes turned in her direction, identified the new arrival, and slid away again, back to their own conversations and pursuits. Adele gave a wave before turning back to the man at whom she was fluttering her lashes, one of the naval officers who had been impressed into the production to play a naval officer. Jane was at the far end of the room, in conversation with Kort.

Jane, whom Augustus thought he loved.

Did love. Had loved? Emma wasn’t sure of anything anymore, least of all the untrustworthy ramblings of the human heart.

Behind her, the door remained closed. Augustus must have slipped around the other way, leaving her to greet Mme. Bonaparte alone.

That had been good of him, she told herself. He had done the prudent thing. To have entered the room together, looking as she did, would have been tantamount to an announcement of an affair. Neither of them wanted that. It would be embarrassing for her, more embarrassing for her than for him. In the eyes of the insular circle that had formed around the First Consul and his wife, she would be either the predator, the bored matron who had taken a poet for a lover, or the prey, the wealthy widow being seduced for her patronage.

Why, then, did she feel quite so shunned?

She felt cold. Cold and tired and strangely wobbly. It had taken more strength than she would have thought to laugh and smile and pretend—because it was pretense—that she didn’t care. It had been even harder to make him stop.

She hadn’t wanted him to stop. Not one little bit. Not at all. It wasn’t just in her lips that she still felt his touch; it was everywhere, memory blurring with memory, awakening desires she thought she had pushed aside long ago, blurred memories of lips and hands and panting breath, sweat and skin and tangled hair.

Only this time, it wasn’t Paul’s face or Paul’s hands that memory provided to her.

Idiot, Emma told herself, and crossed the room to lower herself into the curtsy that the new court etiquette made de rigueur, even at harum-scarum Malmaison, the curtsy that once would have been an embrace.

Mme. Bonaparte raised her up.

“Emma.” A powdered cheek drifted across hers, bringing with it the distinctive scent of roses and rouge that always made Emma feel as though she were fourteen again, accompanying Hortense home from school for a rare weekend away. It had always been a treat to come stay with Mme. Bonaparte, in a house with no routines and no rules, where one might breakfast on sweetmeats and spend the day lollygagging with a novel or grubbing in the garden, just as one chose. “My dear girl.”

Emma felt tears well up in the back of her throat, silly, pointless tears. She had come to Mme. Bonaparte and Malmaison when her marriage with Paul had failed and then again, seeking peace and solitude after the brief madness of her affair with Marston. And here she was again, nearly twenty-five and no wiser, with the scent of roses and rouge, entangling herself where she shouldn’t, playing roulette with her heart and making a general mess of everything.

“Of all surprises, this is the most pleasant,” Emma said, making no effort to hide the moisture in her eyes. Mme. Bonaparte cried easily herself, although only when she stood in no danger of ruining her rouge. She would think they were tears of joy, and be flattered. “I’ve missed you so, Madame.”

Mme. Bonaparte beamed the warmth of her famous close-lipped smile on Emma, well pleased. “We came down early. I couldn’t wait to see how you were getting on.”

“Famously,” Emma said quickly. “We’re getting on famously, especially with Mr. Whittlesby to help with the verse.”

Why had she felt the need to mention him? She might as well take out a column in Le Moniteur, with the heading, “Lady kisses poet. Both agree it meant nothing.”

That wasn’t entirely true. If there had been any kissing, it had gone the other way. He had kissed her, not the other way around.

What did it matter? It had been an aberration. It wasn’t happening again. Friends. They were friends, that was all. Friendship meant more than passion in the long run; she of all people should know that.

Mme. Bonaparte didn’t seem to notice anything amiss. “It was terribly clever of you to hire a poet,” she said complacently. “So much more sensible than trying to write it all yourself. But, my dear, what have you been doing to yourself? You look as though you’ve been playing in the dirt!”

Emma ducked her chin, trying to see down her own front. Her white muslin dress was no longer quite so white. “Oh. Dear.” She looked up at Mme. Bonaparte. “I was backstage in the theatre, trying to put together one of Mr. Fulton’s machines. I’m afraid the floor wasn’t the cleanest.”

Mme. Bonaparte swallowed the story without question. Perhaps, thought Emma, with a dull sense of surprise, because it was true. She had got herself into this state even without Augustus’s ministrations.

Her struggles with Mr. Fulton’s machine seemed like a lifetime ago.

“I’m so very glad you decided to abandon your labors and join us,” Mme. Bonaparte said, drawing her aside with the effortless skill of the accomplished hostess. “There’s something I’ve been wanting to ask you.”

“Yes?” There were people coming and going, the usual gay and glittering crowd who attended on the First Consul’s wife—the Empress, now, Emma reminded herself—but no sign of Augustus.

Perhaps, she thought gloomily, he had fled back to Paris, horrified at his own almost indiscretion. Or maybe he was up in his garret, writing long poems of pain and loss to his inconstant Cytherea.

But why? Why inconstant Cytherea? It was Augustus who had kissed her. Inconstant Augustus, then. In fact, thought Emma, with a twinge of indignation, why was she worrying about Augustus’s feelings? Shouldn’t he be worrying about hers? She encouraged the indignation, nursing it. She was the one who had offered him comfort, just comfort, nothing more. He was the one who had taken advantage of that, seeking a sort of solace she had never offered.

The fact that she had craved it—had welcomed it—was entirely beside the point.

Mme. Bonaparte was looking at her expectantly. Emma realized that the other woman had stopped speaking and was waiting for her to answer.

“I’m sorry,” she said contritely. “Forgive me. I was woolgathering.”

Whatever Mme. Bonaparte’s other vanities, she wasn’t the sort to account inattention a sort of petty treason. “What are we to do with you?” she said fondly. “When you join us at Saint-Cloud, I hope you will pay better attention.”

“At Saint-Cloud?”

Mme. Bonaparte’s face lit like a child’s. “You, my dear, are to be one of my household. A lady-in-waiting! That way, I shall have you with me always.”

“But—” Emma found herself caught, caught off guard, caught in the web of Mme. Bonaparte’s enthusiasm. “But I hadn’t—”

“Thought to be asked?” said Mme. Bonaparte gaily. “My dear girl, how could I leave you aside? Hortense would never forgive me. When I think of the two of you playing in my paint pots and ruining my best hat…”

Emma let the words wash over her, bringing with them a host of rosy-tinted memories of carefree school days and adolescent romps. Would it be such a very bad thing to say yes? She didn’t have anything else she wanted to do or anywhere else she wanted to be. They didn’t really need her at Carmagnac. All the improvements that needed to be made had been made; it was all progressing according to Paul’s plans and M. le Maire had matters well in hand.

If she said yes to Mme. Bonaparte, she would have, in the space of one word, a place and a purpose. Mme. Delagardie would become lady-in-waiting to the Empress. Even Kort couldn’t sneer at that.

Kort and who else? Emma tried not to think about poets.

“We couldn’t possibly go on without you.” Mme. Bonaparte squeezed Emma’s hand languidly in her own. “You’re all but a daughter to me.”

She had married her own daughter off for her own advantage, consigning Hortense to a miserable marriage with a man who despised her.

The reminder acted on Emma like the proverbial bucket of cold water. She didn’t doubt Mme. Bonaparte meant it. But she also didn’t doubt Bonaparte had advised it, or that, while Mme. Bonaparte might be motivated by affection, there was also a sturdy dollop of policy behind it.

Get the American girl, Bonaparte would have said. You mean my Emma, Mme. Bonaparte would have replied. Lovely. We all like Emma.

If she said yes, it meant an end to the autonomy she had earned for herself. It meant curtsying and attending and jumping into a carriage at an hour’s notice whenever the Emperor decided on one of his impromptu migrations. It meant guarding her back and watching her tongue and never being able to know whether any profession of friendship, any amorous overture, was for her own sake or that of her proximity to power.

If she were a daughter, Mme. Bonaparte wouldn’t hesitate to use her as she had her own. She would find herself married off for Bonaparte’s advantage, locked in a loveless marriage, forced to play go-between in the endless games between nations that had somehow supplanted their old and carefree games of prisoner’s base.

This would be a very different sort of prison, but still a prison.

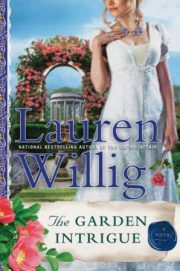

"The Garden Intrigue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Garden Intrigue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Garden Intrigue" друзьям в соцсетях.