Gideon spoke. “But not, sir, without Nettlebed, Chigwell, Borrowdale, Turvey, and the rest of his retinue.”

“You,” said Lord Lionel crushingly, “have behaved throughout in an insolent, heedless, and callous fashion, and may now have the grace to remain silent!”

“There is much in what you say, sir,” admitted Gideon, with a wry twist to his mouth.

“Well, well, that will do!” said his lordship, mollified. “There is no harm done, after all, and I shall not enquire too particularly into what Gilly has been doing. I am not one of those who expect a young man to lead the life of a saint! You are looking very well, Gilly, very well indeed, and that, I must own, makes up for everything!”

The Duke’s hand turned under his, and clasped it. “You are very much too good to me, sir, and I don’t know what I deserve for causing you so much anxiety.”

“Pooh! nonsense!” said his lordship testily. “I know your coaxing ways, boy! Don’t think to cozen me with them! But it is the outside of enough, when you give every idle gossiper in town cause to say that Gideon has murdered you! Not but what it was quite his own fault, and I have no sympathy to waste on him, none at all!”

“But I cannot have you so cross with Gideon,” said the Duke gently. “He is quite my best friend, you know, and, besides, what could he do when I had sworn him to secrecy? And when he heard that I was in a scrape he came to rescue me from it, so it is very hard that he should be scolded now!”

“What scrape have you been in?” demanded Lord Lionel.

“Well, I didn’t mean to tell you, sir, but I think you are bound to hear of it, for rather too many people know it. I was so foolish as to allow myself to be kidnapped, by some rascals who thought to hold me to ransom.”

“That is just what I had feared might happen!” Lord Lionel exclaimed. “All this rubbishing talk of finding out whether you are a man or only a duke, and you are no more fit to fend for yourself than a child in short coats! Well, I hope it may be a lesson to you!”

“Yes, sir,” said the Duke demurely, “but, as it chances, I did fend for myself.”

“Gilly, don’t tell me you let the villains bleed you!” exclaimed his lordship.

“No, sir, I burned down my prison, and came off scatheless.”

Lord Lionel stared at him in great surprise. “Are you trying to humbug me, Gilly?” he asked suspiciously.

The Duke laughed. “No, sir. I thought I had to bestir myself, for I didn’t know that Gideon was coming hotfoot to the rescue. They were not very clever villains, perhaps, which was fortunate. But they did me a great deal of good!”

“Did you a great deal of good?” exclaimed Lord Lionel. “What nonsense you talk, boy! How came it about? Tell me the whole!”

If the Duke did not comply exactly with this request, he told Lord Lionel enough to astonish and shock him very much. But it was evident that he was also pleased to think that his nephew had behaved with such spirit, and he forgot, in his interest in the affair, to enquire how Gideon had come by the knowledge that Gilly had been kidnapped. But he was not at ail pleased to learn that nothing had been done to lay the villains by the heels, and roundly denounced such foolish clemency. “They must be brought to book!” he declared. “You will inform the magistrates, Gilly: you should have done so before you left the district, of course!”

“No, sir, I think not,” the Duke replied tranquilly.

“What you think is of no consequence!” said his lordship. “A pretty state of affairs it would be if all such rascals were to go unpunished! You owe a duty to society, as I have been for ever telling you! Now, do not argue with me, I beg of you!”

“Certainly not, sir: you know I can never bear to do so! I am very sorry for society, but my mind is quite made up. I beg your pardon, but I could not endure to have such a stupid story made known to the world!”

Lord Lionel had been about to scarify him soundly, but this utterance gave him pause. He frowned over it for a moment or two, and at last said grudgingly: “Well, there is something in what you say, but I cannot like it! And there is another thing, Gilly! I do not understand why you have engaged a new steward, without a word to anyone. You will naturally be enlarging your staff, but it will be better to leave such matters in Scriven’s hands. He is far more able to judge of what will suit you than you can possibly be. Not but what,” he added fairly, “this man of yours seem to know his work very well, and to be just the sort of fellow you should have about you. I have nothing to say against him but in future I advise you to let Scriven attend to the hiring of your servants.” He perceived that his son was struggling not to laugh, and directed one of his quelling glances at him. “Now, what do you find to amuse you in that, pray?”

“Nothing, sir!” gasped Captain Ware, wiping his eyes.

Lord Lionel found that his nephew was similarly affected. “Well, well, you are a couple of silly boys!” he said indulgently. “So you wish to remain in Bath, do you, Gilly? You will be squiring Harriet to the balls at the Assembly Rooms, I daresay, and certainly it would not do for you to be driving out to Cheyney late at night. But you would be more comfortable in a set of lodgings, my dear boy, than in an hotel! There are some very tolerable ones to be had, and you may have your own servants to wait on you, and be sure of the beds!”

“Thank you, sir, I shall do very well at the Christopher. It would not be worth the trouble of finding lodgings, for I only stay until Harriet goes to Ampleforth, you know. Shall you join me there, perhaps?”

“No, no, you know very well that I detest hotels! I may as well stay at Cheyney for a few days. It is some time since I was there, and it will do no harm for me to see how things have been going on. Besides, it is quite improper for that fellow, Mamble, to be there without either of us in residence!”

The Duke felt a twinge of remorse. He said contritely: “It is too bad of me! I’m afraid you will dislike it excessively, sir!”

“I daresay,” said Lord Lionel dryly, “that I shall not dislike it as much as you would. I have not lived in the world for fifty-five years without learning how to deal with fellows of that stamp, I assure you. But how came you to fall, in with him, and what is all this nonsense about aiding his son to escape from him?”

By this time, the waiter had come in, and began, under Nettlebed’s severe surveillance, to lay the cover for dinner. It was tacitly assumed that Lord Lionel would partake of this meal, which he did, even going so far as to say that the mutton was not so ill-cooked, and the burgundy—of its kind—quite potable. Nettlebed, who despised all the servants at the Pelican, would not permit the waiter to attend upon his master, but received the various dishes from him in the doorway, so that the Duke was able to regale his uncle uninterrupted with the story of his dealings with Tom. It was not to be expected that his lordship would approve of such unconventional conduct, and he had no hesitation at all in prescribing the proper treatment for boys who played such pranks, but he listened appreciatively to the Duke’s part in them, putting several shrewd questions, and nodding at the answers as though he were well satisfied. Indeed it was felt by both cousins that he had expressed a high measure of approbation when he said: “Well, Gilly, you are not such a fool as I had thought.”

Encouraged by this encomium, the Duke said in his meekest voice: “There is one other little matter which perhaps I should tell you, sir. I daresay you will be paying your respects to Lady Ampleforth?”

“Certainly,” said his lordship.

“Then I think I had better tell you about Belinda,” said the Duke guiltily.

His uncle lifted his brows at him. “Oho! So now we come to it, do we? I thought there was a petticoat in it!”

“No,” said Gideon lazily. “Adolphus has merely been playing the knight-errant. He has been ready to eat me for telling him he is wasting his time. I hope you may have better success with him.”

But Lord Lionel, when he had listened to as much of Belinda’s story as his nephew saw fit to impart, was rather amused. Schoolboys of plebeian parentage were to be deplored, but the intrusion into the Duke’s life of beautiful damsels he regarded as inevitable, and not in the least blameworthy. Whether he believed in the propriety of the Duke’s dealings with Belinda seemed doubtful, but all he said, and that in a tolerant voice, was: “Well, well, it has all been highly romantic, no doubt, and I consider that Harriet has behaved with great good sense. She is a well-trained girl, and will make you an excellent wife! But this Belinda of yours should now be got rid of, my boy.”

“Yes, sir. I—we—hope to establish her creditably,” said the Duke.

Lord Lionel nodded, ready to dismiss the matter. “That’s right. You can afford to be generous, but do not run to extremes! If you do not like to set about the business yourself, I will do it for you.”

“I think, sir, that it will be better if I settle it,” said the Duke firmly.

“As you please,” said his lordship. “It will not hurt you to get out of this scrape by yourself, though I daresay you will be humbugged into paying her far too much. Never be deceived by a pretty face, my boy! All the same, these ladybirds!”

He then favoured his awed young relatives with several surprising reminiscences of his own youth, pointed the moral to them and said that it was high time he drove back to Cheyney. Gideon saw him to the Duke’s chaise. He paused for a minute or two in the doorway of the inn, and said, in a burst of confidence: “You know, Gideon, the boy has not managed so ill! I own, I had not thought he had so much resolution! I begin to have hopes of him. I should not be at all surprised if he turns out to be as good a man as his father. It is a thousand pities he is so undersized, but you may have noticed that he has his own dignity.”

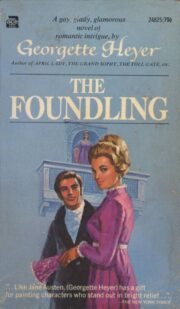

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.