Mr. Mamble drew a large handkerchief from his pocket, and mopped his face with it. “I don’t know what to say!” he announced. “To think of my Tom going about with a Duke, and me being so taken-in—Well, your Grace will have to pardon me if I might perhaps have said anything not quite becoming!”

“Yes, of course I pardon you, but do pray withdraw the charge against me, so that I may escort Lady Harriet home!” said the Duke.

Mr. Mamble hastened to do this, and would have embarked on an elaborate apology had not the Duke cut him short. “My dear sir, pray say no more! I wish you will go with Tom to the Pelican, and await me there. I hope you will give me your company at dinner, for there are several things I wish to talk to you about.”

“Your Grace,” said Mr. Mamble, bowing deeply, “I shall be highly honoured!”

“But it isn’t dinner-time yet!” objected Tom. “I don’t want to go back to the Pelican! Pa took me away from those jolly gardens before I had even seen the grotto! And I had paid my sixpence, too!”

“Well, ask your Papa for another sixpence, and go back to the gardens—that is, if he will permit you to.”

“You do just what his Grace tells you, and keep a civil tongue in your head!” Mr. Mamble admonished his son. “Here’s a crown for you: you can take a hack, and see you ain’t late for dinner!”

Tom, his spirits quite restored by this generosity, thanked him hurriedly, and dashed off. The rest of the party then dispersed, the Duke handing Harriet up into a hackney, and Mr. Mamble setting out in a chastened and bemused frame of mind to walk to the Pelican.

Having given the direction to the coachman, the Duke got into the hackney beside Harriet, and took her in his arms, and kissed her. “Harry, I don’t know how you found the courage to do it, for you must have hated it excessively, my poor love, but I am very sure I am the most fortunate, undeserving dog alive!” he declared.

She gave a gasp, and trembled. “Oh, Gilly!” she said faintly, timidly clasping the lapel of his coat. “Are you indeed sure?”

“I am indeed sure,” he said steadily.

Her eyes searched his face. “When you offered for me, I did not think—” Her voice failed. She recovered it. “I know, of course, that persons of our rank do not look for—for the tenderer passions in marriage, but—”

“Did your mother tell you so, my love?” he interrupted.

“Oh, yes, and indeed I do not mean to embarrass you with—with—”

“Infamous! It is precisely what my uncle said to me! Was that what made you so shy, that dreadful day? I know I was ready to sink! My uncle told me I must not look for love in my wife, but only complaisance!”

“Oh, Gilly, how could he say so? Mama said it would give you a disgust of me if I seemed—if I seemed to care for you very much!”

“What very odd creatures they are! They should deal extremely together. As extremely as we shall!”

She sighed, and leaned her cheek against his shoulder. “How comfortable this is!” she said. “And so delightfully vulgar! Does plain Mr. Dash put his arm round ladies in hackney coaches?”

“When not in gaol he does,” the Duke responded.

Chapter XXII

When Tom returned from his second visit to Sydney Gardens, he was relieved to find his parent in a subdued frame of mind. He had been half afraid that he might discover Mr. Snape at the Pelican, but when he peeped cautiously into the private parlour he saw only the Duke and his father, seated on either side of a small coal fire, and drinking sherry. Mr. Mamble had not imbibed enough to put him at his ease, and he was sitting rather on the edge of his chair, and treating his host with a deference which the Duke disliked even more than he had disliked his earlier manner. He had not neglected, however, to turn Mr. Mamble’s reverence for a title to good account, but had lectured him with great authority on his mishandling of his son.

“He’s my only one, your Grace,” Mr. Mamble explained. “I never had any advantages, not being one who came into the world hosed and shod, like you did, and by the time I was as you see me now—and I fancy I’m as well-equipped as anyone!—I doubt it was too late for me to be thinking of learning to be a fine gentleman. They say black will take no other hue, and black I’ll remain to the end of my days. But if it busts me I’ll see my boy a regular out-and outer! I won’t deny I’ve been disappointed in Snape—though, mind you, he came to me out of a lord’s house, and he was mighty well spoken of, else I wouldn’t have hired him, for I’m one as likes good value for my money, ay, and gets it, what’s more! But a tutor he must have, like the nobs, for if he don’t, how will he learn to behave gentlemanly, and to speak the way you do?”

“Send him to school,” said the Duke.

Mr. Mamble eyed him suspiciously. “Begging your Grace’s pardon, was that what your father did with you?”

“My father died before I was born. I hope he would have, had he lived. As it was, my guardian had so great a care for me that he saddled me with a tutor. But I was very sickly, which Tom is not. Even so, I can assure you that it is wretched for a boy to be educated in such a way. I used to envy my cousins very much, for they were all at school.”

“Ah, I daresay, your Grace!” said Mr. Mamble gloomily. “But the sort of school I want for Tom maybe wouldn’t have him, on account of me not being a gentleman born.”

“I expect,” said the Duke diffidently, “I might be able to help you. I fancy I have an interest at one good school at least.”

Mr. Mamble drew a breath. “By God!” he said, with deep feeling, “if your Grace will speak for Tom there’s no saying where he won’t end!”

Thus it was that by the time Tom came in for his dinner, his parent greeted him with the tidings that if he would be a good boy, and mind his book, and abjure low company, he should go to a school of his Grace’s choosing.

Tom was at once amazed and overjoyed by this unexpected piece of good fortune, and as soon as he could master his tongue expressed his readiness to conform in every way to his sire’s wishes.

Mr. Mamble grunted, regarding him with a fond but sceptical eye. “Ay, I daresay! Prate is prate, but it’s the duck lays the eggs,” he observed. “You be off, and make yourself tidy! You ought to know better than to come into his Grace’s room looking like a clodpole!”

“Oh, bother, he don’t give a fig for that!” said Tom cheerfully. “Oh, sir, shan’t I go to London with you, after all?”

“Yes, indeed you shall, if your Papa will let you,” the Duke said, smiling at him reassuringly. “Perhaps you might come to me after Christmas, and see the pantomime, and all the famous sights. I will invite two of my young cousins as well—only you must not lead them into mischief!”

“Oh, no.’” Tom said earnestly. “I promise faithfully I will not!” Another thought occurred to him; he said anxiously: “And shall I go shooting at your house here? You said I should!”

“Yes, certainly, unless your Papa wishes to take you home directly.”

Mr. Mamble, who was ecstatically rubbing his knees at the thought of his son’s approaching visit to a ducal mansion, said that he didn’t know but what he might not remain in Bath for a few days after all. The Duke mentally chid himself for the feeling of dismay which invaded his breast.

Mr. Mamble became more loquacious over dinner, and by far more natural. He even ventured to ask the Duke why he had elected to wander round the country under a false name.

“Because I was tired of being a Duke,” replied his host. “I wanted to see how it would be to be a nobody.”

Mr. Mamble laughed heartily at this, and said he warranted some people didn’t know when they were well off.

“Oh, Pa!” exclaimed Tom, looking up from his plate. “He isn’t! But I told, him you would pay him back for all the money he spent on me, and you will, won’t you?”

Mr. Mamble said that he would certainly do so, and showed an embarrassing tendency to produce his purse then and there. The Duke hastily assured him that his difficulties were only of a temporary nature.

Mr. Mamble begged him not to be shy of mentioning it if he would like the loan of a few bills. He said that he knew that the nobs were often at low tide through gaming and racing and such, which, though he did not hold with them himself, were very genteel pastimes. He then said in a very lavish way that he hoped that the Duke would not trouble himself about his shot at the inn, but hang it up, since he would count himself honoured to be allowed to stand huff, and would question no expense.

“No, no, indeed I am only awaiting a draft from London!” the Duke said, in acute discomfort. “And pray do not try to reimburse me on Tom’s account! I should dislike it excessively!”

Mr. Mamble, fortified by several glasses of burgundy, then set himself to discover the extent of the Duke’s fortune. The Duke, who had not previously encountered his kind, gazed at him quite blankly, and wondered of what interest his fortune could be to anyone but himself. Mr. Mamble said that he supposed it was derived mostly from rents, and asked him a great many questions about the management of large estates, which, while they certainly showed considerable shrewdness, reduced the Duke to weary boredom. The covers were removed, the port had sunk low in the bottle, and still Mr. Mamble seemed to have no intention of taking his leave. A horrible suspicion that he had brought his baggage from the White Horse to the Pelican, and meant to take up his quarters there, had just entered the Duke’s head when the door was opened, and he looked up to see his cousin Gideon standing upon the threshold. The expression of gentle resignation was wiped from his face. He sprang up, exclaiming: “Gideon!”

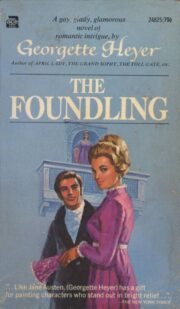

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.