“No, but I am sure it is something dreadful. I believe they are quite bound for a number of years, almost like slaves!”

“Good God! what must I do to get her honourably released, I wonder?”

“Well, do you know, Gilly, I think perhaps I could do that,” she confided, blushing a little.

“No, could you indeed?” he said eagerly. “I am afraid she is a very disagreeable woman. Belinda finds nearly every woman so, I own, but from what she has said to me about Mrs. Puling I do think she is an unkind, tyrannical female. Belinda is frightened to death of her! Would she be satisfied if I offered to pay whatever is owing to her?”

“I daresay she might be, but I don’t think you should appear in the matter at all,” said Harriet firmly. “I have been considering, and I believe it may be something I can do for you quite easily. You know, Gilly, everyone knows that we are to be married in the spring, and all the dressmakers and the milliners want to make my gowns and trim my hats. Because it—it is a great thing to be marrying a Duke, and they think it will be the most fashionable wedding of the season. I cannot but feel that if I were to go to Mrs. Pilling’s establishment, and tell her that I wish her to make me several hats to go with my bride-clothes she would be very willing to forgive Belinda.”

He was much moved. “Harriet, you are the best-natured girl in the world! But from her direction I cannot think that she is at all a modish milliner! You will not like to buy hats from her.”

“I shall not mind, dear Gilly,” replied Harriet simply.

He kissed her hand. “But your mama! What would she have to say?”

“I—I shall not mind that either, if it is for you,” said Harriet. “And I think I shall drive there in Grandmama’s barouche, and take my footman as well as my maid. I expect Mrs. Pilling would like that. And then, you know, she will let it be widely known that she is to make several hats for me, and it will bring her a great deal of much more fashionable custom than perhaps she has ever had.”

He was not very conversant with feminine foibles, but he was dimly aware that his betrothed was making a considerable sacrifice for him. He thanked her warmly, adding after a moment’s thought: “And if you do not like them you may throw them away after all!”

She laughed at that. “Oh, no, how extravagant! I think Mama would certainly have something to say at such shocking waste of money!”

“Would she?” he said, dashed. A happy thought occurred to him. “It doesn’t signify! You may throw them away as soon as we are married, and buy some new ones. Should you like to go to Paris? They have very good bonnets there. If only we can contrive to go without my uncle’s foisting Belper on to us!”

She said earnestly: “Gilly, no one can foist anyone on to you any more!”

He smiled a little ruefully. “Do you think so?”

“I know it. Only if you let them, and you will not.”

“Now I come to consider it,” he remarked, “even my uncle would not expect me to take my tutor with me on my honeymoon! Harriet, I think we should go to Paris! We could have the most diverting time! Should you care for it?”

“Yes, of all things,” she said, looking tenderly at him. “But first we must provide for Belinda!”

“So we must! I was forgetting about her. How vexatious it is! Are you sure you do not mind having her to stay with you until I have found Mudgley?”

“No, indeed!” she assured him.

He looked a little doubtful. “Yes, but I have just bethought me of your grandmother. What shall you tell her?”

“I shall tell her the truth,” Harriet replied. “For, recollect, she already knows that that horrid Lady Boscastle saw you in Hitchin with Belinda! And, if you do not very much object to it, Gilly, I shall tell her about your adventures, because I think she will be very much amused, and pleased.” She smiled a little. “Grandmama is not at all like Mama, you know, and she has been saying to me that although she likes you very well she would like you better still if you were not so very conformable and well-behaved! Of course I shall not tell her about Matthew! And I daresay she would like you to bring Tom to visit her, for she dearly loves anything that makes her laugh. She will be in whoops when she hears of the backward-race! I wonder, will he get into mischief here?”

“My God, I hope not!” exclaimed the Duke. “Perhaps I had best go back to the Pelican, for if he comes home from the theatre and does not find me heaven alone knows what he may take it into his head to do!”

“Perhaps you had,” Harriet said regretfully. “And I must go back to the drawing-room, or people will begin to wonder. Grandmama will let me bring her carriage to fetch Belinda in the morning. What shall you do then? Do you mean to remove to Cheyney?”

“Oh, no, I don’t wish to bury myself there! When Nettlebed has brought me my clothes, and I am fit to be seen again, I think I shall go to the Christopher. Do you attend the dress-balls? Will you stand up with me for all the country-dances?”

She laughed. “Oh, yes, but what will Tom do?”

“Good God, Tom! I must send off an express to his father. I fear he is shockingly vulgar, and will forgive me for my atrocious conduct merely because I am a Duke!”

She rose, and gave him her hand, saying playfully: “It will be well for you if he does, Gilly!”

He kissed her hand, and then her cheek. “Yes, very true! He sounds a terrifying person, and would no doubt make short work of a plain Mr. Dash of Nowhere in Particular. Thank God I am a Duke!”

Chapter XXI

When the news was broken to Belinda that she was to go to stay with a kind lady in Laura Place, she looked very doleful, and said that she would prefer to stay with Mr. Rufford, because ladies were always cross, and she did not like them.

“You will like this lady,” said the Duke firmly. “She is quite a young lady, and she is never cross.”

Belinda looked beseechingly at him. “Please, I would like to find Mr. Mudgley!” she said.

“And so you shall. At least, you shall if I can discover where he lives.”

Belinda sighed. “Mr. Mudgley would not let Mrs. Pilling put me in prison,” she said. “He would marry me instead, and then I should be safe.”

“I shall do my best to find him for you,” promised the Duke;

“Yes, but if you don’t find him I shall not know what to do,” said Belinda sadly.

“Nonsense! We will think of something for you,”

“Oh!” said Belinda. “Will you marry me, sir?”

“No, that he will not!” declared Tom, revolted.

“Why not?” asked Belinda, opening her eyes at him.

“He is not such a gudgeon as to be thinking of marrying, like a stupid girl!” Tom said contemptuously.

The Duke intervened rather hastily. “Now, Belinda, you know you don’t want to marry me!” he said. “You want to marry Mr. Mudgley!”

“Yes, I do,” agreed Belinda, her eyes filling. “But Uncle Swithin took me away from him, and Mr. Ware did not marry me either, so what is to become of me?”

“You will go with Lady Harriet, and be a good girl, while I try to find Mr. Mudgley.”

Belinda’s tears ceased to flow. She looked very much awed, and asked “Is she a lady, sir?”

“Of course she is a— Oh, I see! Yes, she is Lady Harriet Presteigne, and she will be very kind to you, and if you do as she bids you she will not let Mrs. Pilling send you to prison. And what is more,” he added, perceiving that she still seemed unconvinced, “she is going to fetch you in a very genteel carriage! In fact, a lozenge-carriage!”

“What is that?” asked Belinda.

“The crest on the panel—a widow’s crest.”

“I shall drive in a carriage with a crest on the panel?” Belinda said, gazing at him incredulously.

“Yes, indeed you will,” he assured her.

Tom gave a guffaw. “Stupid thing! He’s bamming you!”

Her face fell. The Duke said: “No, I am not. Tom, if you cannot be quiet, go away!”

“Well, I shall. I shall go out to see the sights. Oh, Mr. Rufford, there are some famous shops here! The waiter told me! Would you be so very obliging as to lend me some money—only a very little!—and I swear I will not get into a scrape, or do the least thing you would not like!”

The Duke opened his sadly depleted purse. “It will be no more than a guinea, Tom, for buy some cravats I must, and I am pretty well run off my legs.”

“What a lark!” exclaimed Tom. “Won’t you be able to pay our shot, sir? But Pa will do so, you know!”

The Duke handed him a gold coin. “I trust it will not come to that. There! Be off, and pray do not purchase anything dreadful!”

Tom promised readily not to do so, thanked him, and lost no time in sallying forth. The Duke then persuaded Belinda to pack her bandboxes, and went out to send his express to Mr. Mamble. By the time he had accomplished this, and returned to the Pelican, Belinda had finished her task, and was indulging in a bout of tears. He strove to reassure her, but it transpired that she was not weeping over their approaching separation, but because she had been gazing out of the window, and Walcot Street, which she knew well, put her so forcibly in mind of Mr. Mudgley that she now wished very much that she had never left Bath.

“Well, never mind!” said the Duke encouragingly. “You have come back, after all!”

“Yes, but I am afraid that perhaps Mr. Mudgley will be cross with me for having gone away with Uncle Swithin,” said Belinda, her lip trembling.

The Duke had for some time thought this more than possible, and could only hope that the injured swain would be melted by the sight of Belinda’s beauty. He did not say so to Belinda, naturally, but applied himself to the task of giving her thoughts a more cheerful direction. In this he was so successful that by the time Lady Ampleforth’s barouche set Harriet down at the inn, the tears were dried, and she was once more wreathed in smiles.

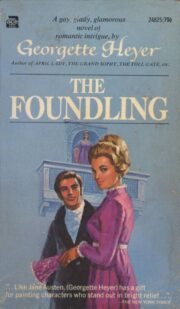

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.