Mr. Liversedge, who had been awaiting his moment, said with admirable common-sense: “If, sir, I may venture to make a suggestion, we should now repair to the Crown, which appeared to be a very tolerable house, and bespeak dinner in a private parlour, and beds for the night I shall give myself the pleasure of mixing for you a Potation of which I alone know the secret. It was divulged to me by one of my late employers since deceased, alas!—a gentleman often in need of revivifying cordials. I fancy you will be pleased with it!”

“We must find his Grace!” declared Nettlebed obstinately.

“It will be dark in another hour,” said Gideon. “Damn it, the fellow’s right! We’ll rack up for the night!” He yawned suddenly. “God, I am tired!”

“Leave everything to me, sir!” said Mr. Liversedge graciously. “That man of yours—a worthy enough fellow, I daresay!—is quite unfit to arrange all those little genteel details so necessary to a gentleman’s comfort. In me you may have every confidence!”

“I have no confidence in you at all,” replied Gideon frankly. “I foresee, however, that we shall end by becoming boon-companions! Lead on, you unmitigated scoundrel!”

Chapter XX

Serenely unaware that he was being pursued by two sets of persons in varying degrees of wrath or exasperation, the Duke conveyed his charges to Bath on the stage-coach, without incident. He made no stay in Reading, arriving there with only just enough time to catch the London to Bath coach. He experienced a little difficulty in procuring places at such short notice, but by dint of bribing several interested persons, he secured one inside seat for Belinda, and two outside ones for himself and Tom. Belinda was inclined to cry when she found that she could not sit on the roof, but by a fortunate chance a delicate-looking young gentleman boarded the coach, and took his place inside. He stared at Belinda in such blatant admiration that she at once became cheerful, and spent a very happy journey encouraging his respectful advances. He did not look to be the sort of dashing blade who would endeavour to seduce her with promises of rings and silken gowns, so the Duke, thankful to be spared the embarrassment of her easy tears, handed her in with no more than a mild request that she would refrain from informing her fellow-passengers that she was travelling to Bath under the escort of a very kind gentleman. He then climbed on to the roof to take his seat beside Tom, and resigned himself to a long and uncomfortable journey. Tom, having begged in vain to be allowed to tool the coach, sulked for some few miles, but revived upon recollecting that he had in his pocket a catapult which he had found time to buy in Aylesbury. His skilful handling of this weapon led to a little unpleasantness with an old lady by the roadside, whose fat pug dog was startled into unwonted activity by a pellet in the ribs, but as no one but the Duke had seen Tom aim the catapult, and he seized and pocketed it the instant he realized what Tom was so surreptitiously engaged upon, no one was able to bring the crime home to the culprit.

“Tom, you are the most shocking boy!” said the Duke severely. “If you have any other devilish engine in your pocket, give it to me at once!”

“No, upon my honour, I have not, sir!” Tom assured him. “But wasn’t it famous when the pug jumped, and ran off yelping?”

“Yes, a splendid shot. If only you will behave with propriety I will take you to Cheyney one day, and give you a day’s real shooting.”

A glowing face was turned towards him. “Oh, sir, will you indeed? I think you are the most bang-up, out-and-out person in the world! Where is Cheyney? What sort of a place is it?”

“Cheyney?” said the Duke absently. “Oh, it’s one of my—It is a house which belongs to me, near a village called Upton Cheyney, some seven miles from Bath, towards Bristol.”

“Is that where we are going?” asked Tom, surprised. “You never said so, sir!”

“No,” said the Duke. “No, we’re not going there,”

“Why not?” demanded Tom. “If there is shooting to be had, it would be much jollier than a stuffy inn in Bath! Do let us, sir!”

The Duke shook his head. He had a very lively idea of what would be the feelings of the devoted retainers in charge of Cheyney were he to arrive there in disgracefully travel-stained clothes, unheralded, unescorted, carrying a cheap valise, and leading Belinda by the hand. He supposed he would shortly be obliged to disclose his identity to Tom, but since he had no desire to be known at the quiet inn he had mentally selected in Bath, and placed little dependence on Tom’s discretion, he decided to postpone the inevitable confession. He said instead that his house was too far removed from Bath for convenience.

His knowledge of Bath’s hotels was naturally confined to such fashionable establishments as York House and the Christopher, in neither of which did he propose to set foot, but he remembered being led, as a boy, by the conscientious Mr. Romsey to gaze reverently upon the facade of the Pelican in Walcot Street, which had once housed the great Dr. Johnson. This respectable inn was no longer patronized by modish people, and had the added advantage of being situated not far from Laura Place, where the Dowager Lady Ampleforth resided.

It was not to be expected that a quiet and unpretentious hotel would meet with the approval of the Duke’s charges. Tom said that if they must put up at an inn he would like to choose the busy posting-house on the Market-place; and Belinda told the Duke reproachfully that she had once conveyed a bonnet to a lady staying at the Christopher, and had formed the opinion that it was a very genteel, elegant hotel, in every way superior to the Pelican. The Duke agreed to it, but gently shepherded his protégés into the Pelican. In the middle of protesting that it was a shabby place Tom was suddenly overcome by a suspicion that Mr. Rufford might not be able to afford to put up at the more fashionable houses, flushed scarlet, and loudly asserted his conviction that they would do very well at the Pelican after all. He then took the Duke aside to remind him that Pa would reimburse him for any monies expended on his behalf, and begged permission to sally forth to see the sights. As it was already time for dinner, this was refused him, but the blow was softened by the Duke’s promise to let him go to the theatre that very evening. Belinda at once said that she would like to go too, and, upon being told that it would be quite ineligible, was only induced to stop crying by a timely reminder of the awful fate in store for her if, by some malign chance, her late employer should be in the audience, and perceive her. She stood in such awe of Mrs. Pilling that she trembled, and turned quite pale, and had to be reassured before she could be brought to eat her dinner.

While the covers were being set upon the table, the Duke called for paper and ink, and dashed off an urgent letter to his agent-in-chief.

“My dear Scriven,” he wrote, “Upon receipt of this, be so good as to despatch Nettlebed to me with such clothing as I may require, and two or three hundred pounds in bills. He may travel in my private chaise, and bring my footman with him. It will be convenient for me to have also my curricle, and the match bays, and these may be brought by easy stages, together with my Purdeys, also at Sale, and the grey mare. I shall send this to you express, and beg you will not delay to follow out its instructions. Yours etc etc Sale.”

He was shaking the sand from his missive when it occurred to him that a little information about himself might be welcome to his well-wishers. He added a postscript: “Pray inform Lord Lionel that I am in excellent health.”

Having, in this masterly fashion, allayed any anxiety or curiosity which his household might cherish, he sealed his letter, directed it, and arranged for its express carriage to London. After that, he joined his young friends at the dinner-table, partook of a neat, plain meal, sped Tom on his way to the theatre, persuaded Belinda to go to bed, and took rueful stock of his appearance.

No amount of wear and tear could disguise the cut and quality of Scott’s olive-green coat, or the excellence of Hoby’s top-boots, but a riding-coat and buckskin breeches, even when in the pink of condition, could not by any stretch of the imagination be considered eligible garments in which to pay an evening visit in Bath. A week earlier, the Duke would have shrunk from the very idea of presenting himself in Laura Place in such a guise, but the experiences through which he had passed had hardened his sensibilities so much that he was able presently to confront old Lady Ampleforth’s porter, who opened her door to him, without a blush. The sound of a violin, and a glimpse of a great many hats and cloaks in the hall conveyed the unwelcome intelligence to him that Lady Ampleforth was entertaining guests. He did not blame the porter for eyeing him askance, but he said in his calm way: “Is Lady Harriet Presteigne at home?”

“Well, sir,” replied the porter doubtfully, “in a manner of speaking she is, but my lady has one of her Musical Parties this evening.”

“Yes, so I hear,” said the Duke, stepping into the hall, and laying down his hat. “I am not dressed for a party, and I shall not disturb her ladyship. Be so good as to convey a message to Lady Harriet for me!”

The porter, having by this time taken in the full enormity of the Duke’s costume, said firmly that he didn’t think he could do that, Lady Harriet being very much occupied.

“Yes, I think you can,” said the Duke tranquilly. “Inform Lady Harriet that the Duke of Sale has arrived in Bath, and wishes to see her—privately!”

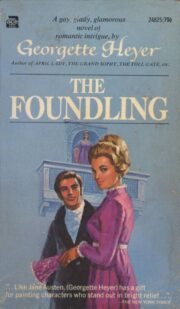

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.