Wragby ushered him into the sitting-room, endured a pungent stricture on the disorder in which his master chose to live, and only just prevented himself from saluting. Lord Lionel, however, recollected without this reminder that he had served in the 1st Foot Guards, and added a few scathing remarks on the customs apparently prevailing in Infantry regiments. Wragby, who was nothing if not loyal, nobly shouldered the blame for the untidiness of the room, said, “Yes, my lord!” and “No, my lord!” at least half a dozen times, and retired in a shattered condition to the kitchen, where he lost no time in venting his feelings on Captain Ware’s hapless batman.

Lord Lionel occupied himself for several minutes in inspecting his son’s library, and uttering “Pish!” in tones of revulsion. Then he paced about the floor for a time, but finding his path impeded by chairs, tables, a paper-rack, and a wine-cooler, he gave this up, and cast himself down in the chair before Gideon’s desk. He had promised his wife that he would write to her as soon as he reached London, and as he had not yet done so he thought he might as well fill in his time in this way as in any other. Amongst the litter of bills and invitation-cards, he found some notepaper, and a bottle of ink. He drew the paper towards him, and then discovered that Gideon, as might, he supposed, have been expected, used a damnable pen that wanted mending. He began to hunt for a knife, and his exasperation mounted steadily. It seemed to him of a piece with all the rest, Gilly’s disappearance included, that Gideon should have no pen-knife. He pulled open one of the drawers in the desk, and turned over a heap of miscellaneous objects in the hope of discovering a knife. He did not find one. He found Gilly’s signet-ring instead.

Captain Ware returned from parade twenty minutes later, and learned from Wragby that his father was awaiting him. He grimaced, but said nothing. His batman made haste to unbuckle his brass cuirass, and his sword-belt; Captain Ware handed his great, crested helmet to Wragby, and lifted an enquiring eyebrow. Wragby cast up both his eyes in a very speaking way, at which the Captain nodded. He stripped off his white gauntlets, tossed them on to the table, flicked the dust from his black-jacked boots, and walked into his sitting-room.

An impartial observer might have thought him a vision to gladden any father’s heart, for his big frame and his dark good looks were admirably suited to the magnificent uniform he wore. But when Lord Lionel, who was standing staring out of the window at the opposite row of chambers, turned to confront him gladness was an emotion conspicuously lacking in his countenance. He was looking appallingly grim, and his eyes held an expression Gideon had never before seen in them.

“I am extremely happy to see you, father,” Gideon said, closing the door. “I hope you have not waited long for me? One of our curst parades! How do you do?”

Lord Lionel ignored both the speech and the outstretched hand. He said, as though the words were wrenched out of him: “For God’s sake, Gideon, where is Gilly?”

“I have not the remotest conjecture,” replied Gideon. “To own the truth, I am a trifle weary of being asked that question.”

“You have not the remotest conjecture?” repeated his father. “Do you expect me to believe that?”

Gideon’s face stiffened; the resemblance between them seemed to grow more marked. “I do, yes,” he said in a level tone.

Lord Lionel held out a hand that shook slightly, “What, Gideon, is this?” he demanded, his hard eyes never wavering from Gideon’s face.

Gideon glanced down at his hand, and saw what lay in the palm of it. “That,” he said, still in that level voice, “is Gilly’s ring, sir. You found it in my desk. I am surprised you do not recognize it.”

“Not recognize it!” exclaimed Lord Lionel. “Do you take me for a fool, Gideon?”

Gideon raised his eyes from the ring, and met his father’s, in a look quite as hard as the one that challenged him. “I did not—no,” he said deliberately. He took the ring out of Lord Lionel’s hand, and restored it to his desk. He turned the key in the lock of the drawer, and removed it. “A precaution I should have taken earlier,” he remarked.

“Gideon!” Lord Lionel’s voice held a note almost of entreaty. “Be open with me, I implore you! Where is Gilly?”

“Don’t you mean, sir, what have I done with Gilly?” suggested Gideon sweetly.

“No!” snapped his lordship. “Nothing would make me believe that you would harm a hair of his head! But when I came upon that ring in your desk—Gideon, do you know what is being said in the clubs?”

“Yes, I have not been so much amused this twelve-month,” replied Gideon. “I own, however, that it does not amuse me very much to discover that you, sir, apparently share the town’s suspicions.”

“Don’t take that tone with me, boy!” said his lordship, flushing angrily. “A pretty thing it would be if I were to suspect my own son!”

“Just so, sir.”

“I do not!—Understand, I do not! But how came you by that ring, Gideon?”

“Oh, I drew it from the corpse’s finger, of course, sir!” Gideon said sardonically.

“Stop trifling with me!” thundered his lordship. “I have told you I believe nothing against you! If I was shocked to come upon a ring in your desk which Gilly always wears you can scarcely wonder at it!”

“I beg pardon, sir. Gilly handed it to me to keep for him. I have neither the desire nor the expectation to wear it.”

Lord Lionel sat down rather limply on the sofa. “I knew something of the sort must have happened. Where has that tiresome boy gone?”

“I have already told you, sir, that I do not know.”

Lord Lionel regarded him frowningly. “Did he dine with you on the day he disappeared, or did he not?”

“He did.”

“Then, confound you, Gideon, what the devil do you mean by telling everyone you had not seen him?” demanded Lord Lionel.

Gideon shrugged, and put up a hand to unhook his tight collar-band. “Being unable to answer further questions, sir, it seemed to me wisest to deny all knowledge of Adolphus.”

“I wish you will not call him that!” said Lord Lionel peevishly. “Do you mean to tell me he did not tell you what his intentions were?”

“He told me merely that he was blue-devilled, sir: a thing I had perceived for myself,” replied Gideon, with a look under his black brows at his father.

“Blue-devilled!” ejaculated Lord Lionel. “I should like to know what cause he had to feel so!”

Gideon’s lips curled. “Would you, sir? Then, by God, I will tell you! My poor little cousin is beset by persons who wish him nothing but good and since he has by far too sweet a disposition to send you, and Scriven, and Nettlebed, and Chigwell, and—but I forget the names of the rest of his retinue!—to the devil, he has been forced to fly from you all. I do not know where he has gone, or how long he means to stay away, or what purpose he has in mind!”

“Are you mad?” demanded his lordship, staring at him. “I have cared as much for Gilly as if he had been my own son !”

“More, sir, more!”

Lord Lionel gave a gasp. “Good God, boy, are you jealous of Gilly?”

Gideon laughed. “Devil a bit, sir! I thank God your affection for me never led you into shielding me from every wind that blew, or hedging me about with tutors, valets, stewards, and doctors, who would not let me set one foot in front of the other without begging me to take heed I did not step into a puddle!”

There was a moment’s silence. Lord Lionel said, almost pleadingly: “He was left to my care, and he was the sickliest child!”

“Oh, content you, sir, no one blames you for your anxiety when he was a child! But it is time to be done with dry-nursing him, and has been so several years! You will not let him be a man: you treat him still as though he were a schoolboy.”

“It is not true!” Lord Lionel said. “I have been for ever telling him it is time that he asserted himself!”

Gideon grinned. “Ay, so you have, and what have you said when he has made an attempt to do so? You desired him to learn to manage his estates, but when he tried so to do did not you and Scriven tell him that his notions were absurd, and that he must be guided by older and wiser heads?”

Lord Lionel swallowed, and said quite mildly: “Naturally Scriven and I—know better than he can—But this is nonsense, after all! You have said as much to me before, and I told you then—”

“Sir, I warned you not so long since that you would not long ride Adolphus on a curb-bit, and you would not attend to me. Well! You see what has come of it!”

Lord Lionel pulled himself together. “Be silent!” he commanded. “You will do well to remember to whom you speak, sir! Let me tell you this! You are answerable for much in having permitted Gilly to go off in this crazy way!”

Gideon lifted his hand. “Oh, no, sir! You mistake! I have no authority over Gilly! I must be the only one of us all to say so, too!”

“Gideon!” said Lord Lionel, striking his fist on the table. “This is beyond the line of what is amusing! You have let that boy go away without one soul to wait on him, or see that he does not fall into some accident, and however well that may do for another young man, it will not do for him! He has never been obliged to fend for himself; he will not know how to go on; he may become ill through some folly or neglect! I had thought you too much attached to him to have been guilty of such behaviour!”

“Believe me, sir, I am so much attached to him that I hope he will fall into all manner of adventures and scrapes! I have a better opinion of Adolphus than you have, or indeed than he has of himself, and I think he will learn to manage very tolerably. He does not yet know his own value. He is unsure because untried. I hope he will not too speedily return to us.”

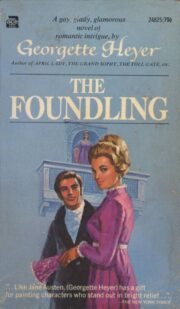

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.