“Yes, yes, I saw the notice! I had looked for a word from his Grace, but I have had no letter from him.” He paused, recalling his conversation with Gilly on the subject of his marriage. “H’m, yes! Well! Nothing had occurred to set up his back? some little nonsense, perhaps? He has sometimes some odd humours!”

“No, my lord, unless it be that his Grace—as I thought—did not quite relish Captain Belper’s companionship,” said Scriven, with his eyes cast down.

“Upon my word I do not blame him!” said his lordship. “I had not thought him to have been such a jackass! I am sorry now that I advised him of his Grace’s coming. But he would not run out of town for such a reason as that!”

The steward gave a little cough. “I beg your lordship’s pardon, but it has seemed to me that his Grace was not quite himself. The very evening before he—before he left us, he would go out alone. He would not have his carriage, nor permit us to summon a chair, my lord. Indeed, when I begged him to let me at least call a linkboy he ran out of the house in quite a pet—if your lordship will excuse the word!”

“Well, I daresay that might put him in a fidget, but it is nothing to the purpose, after all! I own that it is a little disturbing that he should stay so long away, but young men are thoughtless, you know! Tomorrow, if there should be no word from him I will make some discreet enquiries. Captain Ware no doubt knows who are his intimates. We shall clear up this mystery speedily enough, I daresay.”

On this bracing note, he dismissed Scriven. But when he was alone he sat for quite an appreciable time, an untasted glass of wine in his hand, and his eyes fixed frowningly upon the glowing coals in the grate. He remembered that Gilly had been foolishly agitated when the question of his marriage had been broached. He hoped that the boy had not made his offer against his will, and fallen into a fit of dejection. He was so quiet there was never any knowing what was in his head. Suddenly his lordship remembered that Gilly had had some odd notion of going to London alone, and of staying in an hotel. It really began to look as though he had had some plan of escaping from his household from the start. But why he should wish to do so Lord Lionel could not imagine. Had he been a wild young blade, like Gaywood, one would have supposed that he was bent on kicking up a lark, but it was surely the height of absurdity to cherish such a suspicion of poor Gilly. Lord Lionel could only hope that his son would be able to throw some light on a problem which was beginning to make him feel extremely uneasy.

Chapter XV

Lord Lionel passed a disturbed night. He came down to breakfast in the expectation of finding a letter from his errant nephew awaiting him; but in despite of the fact that the sum of one pound was paid to the Post Office every year by Mr. Scriven, out of the Duke’s income, to ensure the early delivery of the mail, no such letter gladdened his lordship’s eyes. Matters did not, of course, appear to be quite so desperate as they had seemed during the chill small hours, but there was no denying that Lord Lionel had little appetite for his breakfast. He was curt with Borrowdale, and even brutal to Nettlebed; and when a message was brought to him that Captain Belper had called he instructed the footman to tell this unwelcome visitor that he had gone out.

In a very short time he did go out. He spent the better part of the morning at White’s and at Boodle’s, and, being no fool, was soon able to discern that Gilly’s disappearance was the main topic of conversation amongst the haut ton. Interesting discussions ended abruptly with his entrance into a room; and from several hints that were dropped he discovered, to his wrath, that speculation was rife on his son’s part in the mystery. He had almost gone to Albany when he bethought him of an old crony, and strode off instead to Mount Street. Whatever the on-dits of town might be, it was certain, he reflected grimly, that Timothy Wainfleet would know them all.

He found his friend at home, huddled over a fire in his book-room, and looking at once wizened and alarmingly alert. Sir Timothy welcomed him with exquisite courtesy, gave him a chair by the fire, and a glass of sherry, and murmured that he was enchanted to see him. But it did not seem to Lord Lionel that Sir Timothy was quite as enchanted as he averred, and, being a direct person, he said so, in express terms.

“Dear Lionel!” said Sir Timothy, faintly protesting. “Indeed, you wrong me! Always enchanted, I assure you! And how are the pheasants? You do shoot pheasants in October, do you not?”

“I have not come to talk to you of pheasants,” announced Lord Lionel. “What is more, you know as well as I do when pheasant-shooting begins!”

Sir Timothy’s shrewd grey eyes twinkled ruefully. “Yes, dear Lionel, but I apprehend that I would rather talk of pheasants than—er—than what you have come to talk about!”

“Then you have heard of my nephew’s disappearance?” demanded Lord Lionel.

“Everyone has heard of it,” smiled Sir Timothy. “Yes! Thanks to the folly of Gilly’s steward, who, I find, could think of nothing better to do than to spread the news at White’s! Now, we are old friends, Wainfleet, and I look to you to tell me what is being said in town! For what I hear I don’t like!”

“I wonder why I did not tell my man to deny me?” mused Sir Timothy. “I never listen to gossip, you know. Really, I do not think I can assist you!”

“You listen to nothing else!” retorted Lord Lionel.

Sir Timothy looked at him in melancholy wonder. “I suppose I must have liked you once,” he said plaintively. “I like very few people nowadays; in fact, the number of persons whom I cordially dislike increases almost hourly.”

“All that is nothing to the matter!” declared his lordship. “There is a deal of damned whispering going on in the dubs, and I look to you to tell me what it is I may have to fight. What are the fools saying about my nephew?”

Sir Timothy sighed. “The most received theory, as I apprehend, is that he has been murdered,” he replied calmly.

“Go on!” commanded Lord Lionel. “By my son?”

Sir Timothy winced. “My dear Lionel!” he protested. “Surely we need not waste our time in discussion of absurdities?”

“I am one who likes to see his way!” said his lordship. “If I have to remain here a week, you shall tell me the whole!”

“God forbid!” said his friend piously. “I find you very unrestful, you know: not at all the kind of guest I like to receive! Do pray understand that I do not set the least store by the whisperings of ill-informed persons! But you will agree that there is food and to spare for gossip. I am informed—of course I do not believe it!—that the last man to see your nephew was his cousin, with whom he is said to have dined. A circumstance—always remember, my dear Lionel, that I do but repeat what I hear!—which Captain Ware denies. One Aveley met Sale upon his way to your son’s chambers. No one has set eyes on him since, you know! Malicious persons—the town is full of them!—pretend to perceive a link between this fact, and the notice which lately appeared in the Society journals. So nonsensical! But you know what the world is, my dear friend!”

“My son, in a word,” said Lord Lionel, staling at him with narrowed eyes, “is held to have murdered his cousin upon learning that he is about to marry, and beget heirs?”

SirTimothy raised a deprecating hand. “Not by persons of discrimination, I assure you!” he said.

“It is a damned lie!” said Lord Lionel.

“Naturally, my dear Lionel, naturally! Yet—speaking as your friend, you know!—I do feel that a little openness in dear Gideon—a little less reserve—would be wise at this delicate moment! He has not been—how shall I put it?—precisely conciliating, one feels. In fact, he preserves a silence that is felt to be foolishly obstinate. Strive to consider the facts of this painful affair dispassionately, Lionel! Your nephew—quite one of our wealthiest peers, I am sure! so gratifying, and due in great part, I am persuaded, to your excellent management of his estates!—announces the tidings that he is about to be wed; and within twenty-four hours he visits your son, who afterwards denies all knowledge of his whereabouts. He is not seen again; his servants search for him all over town; you come post from Sale; and the only undisturbed member of his entourage appears to be Gideon, who pursues his usual avocations with unimpaired calm. Now, do understand that not one word of this would you have had from my lips had you not forced me to speak, almost, one might say, at the pistol-mouth! The tale is as nonsensical as most rumours are. I advise you to ignore it. Let me give you some more sherry!”

“Thank you, no! I am going instantly to see my son!” said Lord Lionel harshly. “I collect that I have nursed my nephew’s fortune so that my son may ultimately benefit? Are you sure that I have had no hand in his disappearance?”

“That,” said Sir Timothy gently, “would be absurd, Lionel.”

Lord Lionel left him abruptly, and strode off down Piccadilly, his brow black, and his brain seething with rage. He had naturally no suspicion of his son, but the apparently well-attested information that he must have been the last man to have seen Gilly greatly disturbed him. If it were true, he was no doubt in Gilly’s confidence, but what could have possessed him to have aided and abetted Gilly in this foolish start? Gideon must surely know that his cousin could not be permitted to wander about the country like a nobody, a prey to chills, adventurers, highwaymen, and kidnappers! By the time his lordship had reached Albany, he had worked himself up into a state of anger against his son which demanded an instant outlet. This was denied him. Wragby, admitting him into Gideon’s chambers, said that the Captain had gone on parade, and was not expected to return for another half-hour at least. Lord Lionel glared at him in a way which reminded Wragby of his late Colonel, and said in one of his barks: “I will await the Captain!”

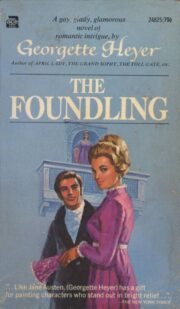

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.