“Bird-witted she may be,” replied Mr. Liversedge fair-mindedly, “but where, I ask you to tell me, Joe, could you find a more lovely piece?”

The gentleman in riding-dress paused between mouthfuls to heave a deep sigh. “Ah, if ever I see such a rare bleached mort!” he said, shaking his head. “What a highflyer, Sam! But no sense in her cockloft, which makes her dangerous ware for a man like me. Else I would have—”

“You would have done no such thing, Nat Shifnal, as I have erstwhile made plain to you!” said Mr. Liversedge. “Nothing could be more fatal for a man in my position than to be bringing damaged goods to market!” He stretched out a hand for the dish on which a somewhat mutilated sirloin of beef reposed, and drew it towards him. “I will trouble you for the carving-knife, Joe,” he said, with dignity.

His brother pushed it across the table. “She’s loped off in pudding-time, that’s what I say and will hold to!” he announced. “If you had of gone on the dub-lay, Sam, it’s low, but not a word would you have heard out of me! Nor I wouldn’t have blamed you for turning bridle-cull, like Nat here. But you took and tried to be a petticoat-pensioner, and that’s what I don’t hold with, and nothing will make me say different!”

Mr. Liversedge replied in a lofty tone that he would thank his brother not to use such vulgar terms to him. “There is, I will grant, a certain distinction attached to those who embrace the High Toby as their profession. But the dub-lay—or, as I prefer to call it, the very ignoble calling of a common pickpocket—is something I thank God I have never yet been obliged even to contemplate!”

“No, because every time as you’re nippered it’s me as stands huff!” retorted Mr. Minims.

“Easy, now, easy!” begged Mr. Shifnal placably. “I don’t say as Sam done right this time, but there’s no denying, Joe, he’s got gifts. For one thing, he talks as nice as a nun’s hen; and for another, there ain’t anyone to touch him for drinking a young ’un into a fit state for plucking.”

“Then let him stick to it!” retorted Mr. Mimms. “I got nothing against that lay, but petticoat-pensioners I can’t stomach!”

Mr. Shifnal regarded Mr. Liversedge curiously. “How did you come to be diddled by a greenhorn, Sam? It ain’t like you, I’ll cap downright! By what Joe tells me, you shouldn’t have had trouble in plucking that pigeon.”

Mr. Liversedge described an airy gesture with one white hand. “The greatest amongst us must sometimes err. I own that I erred. Talking pays no toll, or I might be tempted to say much in extenuation of what I admit to have been a misjudgment.”

“It wouldn’t be no use talking them breakteeth words to Nat,” said Mr. Mimms caustically. “He ain’t had your advantages, Sam, for all he’s able to pay his shot, and don’t have to come down on me for the very bread he puts in his mummer.”

Mr. Liversedge’s bosom swelled perceptibly, but after looking hard at his brother for a moment he apparently decided to ignore his lapse from good taste. He said: “What I ask myself is, Who was he?”

“If you was to be asking yourself how you was to set about making a living, there’d be some sense in it,” commented the aggressive Mr. Mimms. “It don’t matter to none of us who that downy young ’un was. I’ll allow he looked like a flat, but he knocked you into horse-nails, which I hope and pray as it will be a lesson to you not to meddle with swells again!” He perceived that he was not being attended to, Mr. Liversedge having fallen into a brown study, and added bitterly: “There you go! A-thinking up some more of your cork-brained lays! You won’t be happy till you’ve got yourself into the Whit, and me along with you!”

“Be silent, Joseph!” commanded Mr. Liversedge. “I must and shall make a recover!” He passed a hand across his brow as he spoke, and rather impatiently tore off the Duke’s handkerchief. “That young addle-plot was very perfectly acquainted with all the circumstances of this affair,” he said. “In a word, he was deep in Ware’s confidence. I hold to my original conviction that his purpose in coming here was to treat with me. Had I not, for a fatal instant, lowered my guard, I fancy I should now be in possession of a substantial sum of money—of which you, Joe, would have had your earnest, I assure you.”

“That’s handsomely said, Sam,” approved Mr. Shifnal. “What’s more, Joe don’t doubt you’d have paid him his earnest, nor no one that knows you.”

“No, I don’t,” said Mr. Mimms. “Because I’d ha’ seen to ityou did. But not one meg have I had out of you, Sam, and all I got is you borrowing from me to take and hire a shay to fetch that silly wench here, which I never wanted, nor don’t hold with!”

Mr. Liversedge disregarded him. “He was well-breeched,” he said slowly. “I perceived it at the outset. That olive coat—I caught but a glimpse of it beneath his Benjamin, but I flatter myself I am not easily deceived in such matters—was only made by a tailor patronized by members of the haut ton. Not a dandy, no! But there was an air of elegance—how shall I put it? A—”

“He was a flash-cull,” suggested Mr. Shifnal helpfully.

Mr. Liversedge frowned. “He was not a flash-cull!” he said with some asperity. “He was a gentleman of high breeding. His hat bore the name of Lock upon the band: I observed it when he laid it brim upwards on the table. That may mean little to you: it conveys to me the information that he is one who frequents the haunts of high fashion. During that period in my life when I acted as a gentleman’s gentleman, I became acquainted, with the nicest particularity, with every detail of an out-and-out swell’s attire. I recognized at a glance in this greenhorn a member of the Upper Ten Thousand.”

Mr. Shifnal being plainly out of his depth, Mr. Mimms kindly translated this speech for him. “He was as spruce as an onion,” he said.

“If you choose so to put it,” agreed Mr. Liversedge graciously. “Take only this handkerchief! Of the finest quality, you observe, and the monogram—” Suddenly he stopped short, as an idea occurred to him, and subjected the handkerchief to a closer scrutiny. It had been hemmed for the Duke by the loving hands of his nurse, who was a notable needle-woman. In one corner she had embroidered a large S, and had had the pretty notion of enclosing the single letter in a circle of strawberry leaves. “No,” said Mr. Liversedge, staring at it. “Not a monogram. A single letter. In fact, the letter S.” He looked up, and across the table at his brother. “Joseph,” he said, in an odd voice, “what does that single letter S suggest to you?”

“Nothing,” replied Mr. Mimms tersely.

“Samuel,” suggested Mr. Shifnal, after profound mental research. He saw an impatient frown on Mr. Liversedge’s brow, and corrected himself. “Swithin, I should say!”

“No, no, no!” exclaimed Mr. Liversedge testily. “Where are your wits gone begging? Joseph, what, I ask you, are these leaves?”

Mr. Mimms peered at the embroidery. “Leaves,” he said.

“Leaves! Yes, but what leaves?”

“Sam,” said Mr. Mimms severely, “it’s mops and brooms with you, that’s what it is! And if it was you as prigged a bottle of good brandy from the tap-room, and me blaming it on to Walter—”

“Joseph, cease trifling! These are strawberry leaves!”

“Very likely they may be, but what you’ve got to get into a passion for because the swell has strawberry—”

“Ignorant wretch!” said Mr. Liversedge, quite agitated. “Who but a Duke—stay, does not a Marquis also—? But we are not concerned with Marquises, and we need not waste time on that!”

“You’re right, Joe,” said Mr. Shifnal. “He is lushy! Now, don’t you go a-working of yourself into a miff, Sam! No one won’t waste any time on Markisses!”

“You are a fool!” said Mr. Liversedge. “These leaves stand in allusion to the rank of that greenhorn, and this letter S stands for Sale! That greenhorn was none other than his Grace the Duke of Sale—whom Joseph, by his folly in leaving this hovel to feed a herd of grunting swine, has let slip through his bungling fingers!”

Mr. Mimms and Mr. Shifnal sat staring at him in blank amazement. Mr. Mimms found his tongue first. “If you ain’t lushy, Sam, you’re dicked in the nob!” he said.

Mr. Liversedge paid no attention to him. A frown wrinkled his brow. “Wait!” he said. “Let us not leap too hurriedly to conclusions! Let me consider! Let me ponder this!”

Mr. Mimms showed no desire to leap to any other conclusion than that his relative had taken leave of his senses, and said so. He filled up his glass, and recommended Mr. Shifnal to do the same. For once, Mr. Shifnal did not respond to this invitation. He was watching Mr. Liversedge, quick speculation in his sharp face. When Mr. Mimms would have broken in rudely upon his brother’s meditations, he hushed him, requesting him briefly to dub his mummer. “You let Sam be!” he said. “Up to every rig and row intown, he is!”

“To whom,” demanded Mr. Liversedge, suddenly, “would young Ware turn in his dilemma? To his father? No! To his cousin, Joseph! To his noble and affluent cousin, the Duke of Sale! You saw him; you even conversed with him: was not his amiability writ large on his countenance? Would he spurn an indigent relative in his distress? He would not!”

“I don’t know what he done to no relative,” responded Mr. Mimms, “but I know what he done to you, Sam!”

Mr. Liversedge brushed this aside. “You are a sapskull,” he said. “What he did to me was done for his cousin’s sake. I bear him no ill-will: not the smallest ill-will! I am not a man of violence, but in his shoes I might have been tempted to do as he did. But we run on too fast! This is not proved. And yet—Joseph, it comes into my mind that he told me he was putting up at the White Horse, and this gives me to doubt. Would he do so if he were indeed the man I believe him to be? One would say no. Again we go too fast! He did not wish to be known: a very understandable desire! For what must have been the outcome had he come to me in his proper person? What, Joseph, if a chaise with a ducal crest upon the panel had driven up to this door? What if a card had been handed to you bearing upon it the name and style of the Duke of Sale? What then?”

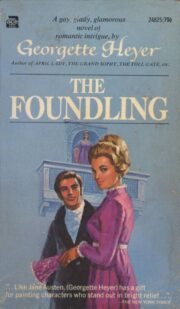

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.