“Tell me,” he said, “when you were in Oxford with Mrs.—Mrs.—I don’t recall the name, but the lady who was thought to be your aunt—”

“Oh, she was not my aunt!” Belinda said. “I did not like having to live with her at all, for she was so bothersome, and very often cross with me.”

“But who was she?” he asked.

“I don’t know. Mr. Liversedge was very friendly with her, and he said I should stay with her and do just what she told me.”

He could not help smiling. “And was that to make my—to make Mr. Ware fall in love with you?”

“Yes,” she replied innocently. “I did not mind that, for we went pleasuring together, you know, and he was excessively kind to me, and he said he would marry me, too, and then I should have been a grand lady, and had my carriage, and silk dress besides.”

“Did you wish very much to marry him?”

“Oh, no!” Belinda replied placidly. “I didn’t care, if only I might have all the things Uncle Swithin said I should. He said it would be more comfortable for me if Mr. Ware gave me a great deal of money, and I think it would have been, because he was so jealous, you know, that there was no bearing it. Why, when I only went out to get a pound of black pudding from the pork-butcher, and a gentleman carried the basket for me, there was such an uproar! And he read poetry to me, too.”

“That was certainly very bad!” the Duke said gravely. “But tell me what happened after Mr. Ware—when you were no longer expecting to marry him! Did you run away from that lady?”

“Oh, no, she would not keep me any longer, because she quarreled dreadfully with Uncle Swithin, and she said he was a Jeremy Diddler.”

“What in the world is that?” he enquired, amused.

“I don’t know, but I think Uncle Swithin wouldn’t pay her any money, and she said he had promised it to her for taking care of me. She was as cross as a cat! And Uncle Swithin told her how we should all of us have money from Mr. Ware, but there was an execution in the house, you know, and she would not stay there any more. It is very fidgeting to have an execution in your house, for they take away the furniture, and there is no knowing how to go on. So Uncle Swithin fetched me away in an old tub of a carriage, which was so horrid! I was stuffed to death! And we had to go in the middle of the night, and that was uncomfortable too.”

“He took you to that inn? Is it possible that he meant to keep you there?”

“Well, he could not help doing so,” explained Belinda. “Poor Uncle Swithin! he has so very little money left, and Mr. Mimms is his brother, so you see he does not have to pay him to stay there. And of course we was expecting Mr. Ware to send us a great sum of money, and then we might have been comfortable again. But Uncle Swithin says all is ruined, and it was my fault for not calling to Mr. Mimms to stop you when you went away. But he never told me I should do so!”

“Don’t you think,” he suggested gently, “that you will like just as well to go to your friend as to have a great sum of money?”

Belinda reflected, and shook her head. “No, for if I had the money I could also go to visit Maggie Street,” she said simply.

This was so unanswerable that the Duke abandoned the subject, together with a half-formed resolve to point out to Belinda the reprehensible nature of Mr. Liversedge’s attempts to extort money from undergraduates. Something told him that Belinda’s intelligence was not of the order that readily appreciated ethical considerations.

In a short time, Tom returned to the inn, his mission accomplished. If Mr. Rufford would step down to the George, he said, to confirm the arrangement he had made on his behalf, a chaise could be hired, and would be sent round to the White Horse as soon as it was needed.

The Duke was not very anxious to visit the George, where he had several times stopped on his way to his estates in Yorkshire, to change his horses, but he did not think that he had ever alighted there, and could only hope that he would not be recognized. He desired his protégés to pack their few belongings, and sallied forth, requesting Mrs. Appleby, whom he met at the foot of the stairs, to prepare his reckoning. Mrs. Appleby allowed him to see by her manner that he had sadly disappointed her; and the waiter, hovering in the background, plainly regarded him in the light of a hardened libertine.

In the event, no one whom he interviewed at the George showed the smallest sign of recognizing him. He thought the luck was miraculously with him, until it occurred to him, on his way back to the White Horse, that, had he wished to do it, he might have found it difficult to convince the landlord and the servants at the George that an unattended gentleman, staying at the White Horse and in need of a hired chaise, could possibly be his Grace the Duke of Sale. He reflected then that it was to be hoped he would have no occasion to prove his identity, since he had taken care to leave his visiting cards at Sale House, and had handed over to Gideon his seal ring.

When he reached the White Horse again, he found that although Belinda had packed her bandboxes, Tom was by no means ready to depart, having, in fact, made no attempt to stow away the articles of apparel procured for him into the carpet-bag which was all the Duke had been able to find in Baldock for the carriage of his effects. Tom had expended some part of the guinea the Duke had given him on the acquisition of a fascinating new toy, called, not without reason, Diabolo. He had already succeeded in breaking a water-bottle, and a cherished vase of unsurpassed hideousness which Mrs. Appleby stated had belonged to her husband’s grandfather and was quite irreplaceable. The Duke was greeted on his arrival with a strongly worded complaint from Mrs. Appleby, and a simple request from Belinda to buy her a Diabolo too. However, Tom, who found that he did not excel in manipulating the toy, said loftily that it was a stupid thing, and very handsomely made Belinda a present of it. But the Duke was obliged to do his packing for him, and by the time he had left Tom to strap up the carpet-bag, and had dealt with his own effects, and settled his reckoning with Mrs. Appleby, the hired chaise was at the door. He saw his charges into it, directed the post-boy to take them to the Sun Inn at Hitchin, and turned to take his leave of Mrs. Appleby.

“Mark my words, Mr. Rufford, sir,” she said bodingly, “you will live to regret it, for if ever I saw a light-skirt, which I never thought to soil my lips with such a word, I see one this day!”

“Nonsense!” said Gilly, and sprang up into the chaise.

“This,” declared Belinda buoyantly, “is beyond anything great, sir! To be jauntering about in a private chaise like a real lady, as fine as a star! If Mrs. Pilling were to see me now she would not credit her eyes, I daresay! Oh, if only Mr. Liversedge does not find me, and take me back again!”

“Mr. Liversedge,” said Gilly, “has a great deal of effrontery, but hardly enough, I dare swear, for that! Let us put him out of our minds!” He saw that she was still looking vaguely scared, and smiled. “There is nothing more he can do, Belinda, after all! Ten to one, he is by this time turning his mind into other channels.”

But little though he knew it he had wronged Mr. Liversedge. That gentleman had found himself so very far from well on the previous evening that he had been quite unable to bend his powerful mind to any more difficult problem than how he could most expeditiously cure the shocking headache that nearly blinded him. He bad gone to lie down upon his bed, and had responded to a suggestion that he would be better for a bite of supper only by a hollow groan. Mr. Minims, regarding him with a scornful eye, offered him consolation in the form of a reminder that he had warned him that no good could come of flying at game too high for him.

“You leave them swell bleaters be, Sam!” he adjured the prostrate sufferer. “Then maybe you won’t have no broken head another time!”

Mr. Liversedge opened a bloodshot eye. “Swithin!” he found strength to utter.

“Sam you was christened, and much good it done you to go a-giving yourself a silly flash name like Swithin!” said Mr. Mimms severely. “Well, if you don’t want no peck and booze there’ll be more for them as does, that’s one thing!”

On this cheering thought, he departed, leaving his afflicted brother to spread a cold compress over his head and to take another pull at the brandy bottle.

It was some hours later before Mr. Liversedge felt able to rise from his couch, and to totter downstairs to the kitchen. He still wore the Duke’s handkerchief knotted round his head, and he had by no means recovered his complexion, but the pangs of hunger had begun to attack him. He pushed open the kitchen door, and found that his brother was entertaining a guest, a thin, wiry gentleman, who wore a riding-suit of sober-coloured cloth, and a pair of well-fitting boots that seemed to have seen much service. He had a pair of bright grey eyes, which lifted quickly and warily as the door opened. He was in the act of consuming a prodigious portion of cold beef, but he held his knife suspended for an instant, until he saw who it was that had entered, when he relaxed, and waved the laden knife at Mr. Liversedge, saying cheerfully: “Hallo, Sam, old gager!”

Mr. Mimms, who was seated on the opposite side of the table, engaged in inspecting a collection of watches, purses, fobs, and rings, cast an appraising look at Mr. Liversedge, and said: “That flash mort of yours has loped off.”

Mr. Liversedge drew up a spare chair, and lowered himself into it, “Where to?” he demanded.

“I dunno, nor I don’t care. How you ever come to think there was any good to be got out of such a bird-witted wench downright queers me! Good riddance to her, that’s what I say!”

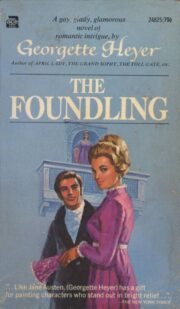

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.