“Then I think I had better drive you to the inn where I am putting up, and see what can be done for that black eye of yours. What is your name?”

The boy gave another sniff. “Tom,” he divulged reluctantly. “I want to go to London. And I would have gone, too, only that I asked those men the way to Baldock, and they said they would put me on the road, and then—and then—” He ground his teeth audibly, and said in a kind of growl: “I suppose I was a regular green one, but how was I to tell—?”

“No, indeed, it is the kind of thing that might happen to anyone,” the Duke agreed, propelling him gently towards the gig. “Up you get!”

“And I landed one of them a couple of wisty castors!” Tom told him, allowing himself to be helped into the gig. “Only they had cudgels, and that is how it came about. And they took my five pounds, and my watch, which Pa gave me, and when I came to myself they were gone. I don’t care for having my canister milled, but it is too bad to have taken all my money, and if I could catch them Pa would have them transported!”

The Duke, having put him safely into his seat, went to the cob’s head, and began to turn the gig in the narrow space available for the manoeuvre. He was not at all inclined to take his youthful protégé to an inn of such apparent ill-fame as the Bird in Hand, even though it seemed highly probable that Tom might there realize his wish of catching his assailants; and he decided that his business with Mr. Liversedge would have to be postponed until the next day. Having turned the gig, he mounted on to the box seat, gathered, up the reins, and gave the cob the office to trot homewards. Tom sat slumped on the seat beside him, sunk in depression, sniffing at intervals, and wiping his nose with a grubby handkerchief. After an interval, he said with would-be civility: “I don’t know why you should put yourself to this trouble, sir. I am sure you need not. I daresay I shall do very well when my head stops aching.”

“Oh, you will be as right as a trivet!” Gilly said. “Had you a bag with you, and did the thieves steal that as well?”

Tom fidgeted rather uncomfortably. “No. That is—Well, the thing is I couldn’t bring my portmanteau, sir, because—Well, I couldn’t bring it! But then, you know, I had my money, and I thought I could buy anything I might need.”

The Duke, feeling that he had much in common with his young friend, nodded understandingly, and said that it did not signify. “I expect one of my nightshirts will not fit you so very ill. How old are you?”

“Fifteen,” replied Tom, a hint of challenge in his voice.

“You are very big! I had thought you older.”

“Well, I do think anyone might suppose me to be seventeen at least, don’t you?” Tom said, responding to that gratifying remark, and speaking in a far less belligerent tone. “And I am very well able to take care of myself—in general. But if sneaks set upon one two to one there is no doing anything! And I shall never have such a chance again, because they will watch me so close—Oh, it is too bad, sir! I wish I was dead! They would have been sorry then! At least, Pa would, but I daresay Mr. Snape wouldn’t have cared a button, for he’s the greatest beast in nature, and I hate him!”

“Your schoolmaster?” hazarded the Duke.

“Yes. At least, he is my tutor, because Pa wouldn’t have me go to school, which I had liefer have done, I can tell you! And when it came to his reading to me in the chaise, not even something jolly, like Waverley, or The Adventures of Johnny Newcome, which is a famous book, only of course he took it away from me—he would!—but the horridest stuff about Europe in the Middle Ages! As though anyone could listen to such dry fustian! And in the chaise, sir! There was no bearing it any longer!”

“It was certainly very bad,” agreed the Duke sympathetically. “But they will all do it! I remember my own tutoronce tried to interest me in Paley’s Natural Theology upon one of our journeys from Bath to S—to my home!” he corrected himself swiftly.

“That sounds as though it would be just as dry!” said Tom, impressed.

“Oh, worse!”

“What did you do, sir?”

The Duke smiled. “I was very poor-spirited: I tried to listen.”

“Well, I hit Mr. Snape on the head, and ran away!” said Tom, with a return to his challenging manner.

The Duke broke into his low laugh. “Oh, no, did you? But how did you contrive to do that when you were driving along in a chaise?”

“I couldn’t, of course, but the thing is we changed horses at Shefford, and then when we had not gone a mile out of the town the perch broke, and we were obliged to stop. And the postilion was to ride back to Shefford to procure another chaise for us, and when he was gone old Snape said we would take a walk in the wood, and that would not have been so bad, but what must he do but pull his stupid book out of his pocket again, just when I had seen a squirrel’s drey—at least, I am pretty sure it was one, and I would have found out if he had but let me alone! But he is such a prosing, boring beast he don’t care for anything worth a fig, and he said we would read another chapter, and so I floored him. I have a very handy bunch of fives, you know,” he said, exhibiting his large fist to the Duke, “and I dropped him with a flush hit just behind his ear. And if you are thinking, sir,” he added bitterly, “that it wasn’t a handsome thing to do, to hit him from behind, I can tell you that I owe him something, for he is a famous flogger, and is for ever laying into me. Did your tutor too?”

“No, very seldom,” replied the Duke. “But he was a great bore! I fear I could never have floored him, for I was not a big fellow, like you, but I own I never thought of doing so. Did you knock him out?”

“Oh, yes!” said Tom cheerfully. “I don’t think he is dead, though. I could not wait to see, of course, but I should not think he could be. And in a way it will be as well if he is not, because they would hang me for it, wouldn’t they?”

“Oh, I don’t suppose it is as bad as that!” Gilly consoled him. “Did you then make your way from Shefford?”

“Yes, and the best of it is he will not know which way I went, and I kept to the woods, and the fields, so all the chaises in the world won’t help him. I thought I would get on the coach for London, and see all the sights there, which he would not let me do, horrid old addle-plot! Only fancy, sir! We drove up from Worthing, and we spent just one night in London, and the only thing he would let me see was St. Paul’s Cathedral! As though I cared for that! Not even the wild beasts at the Exeter Exchange! Of course I knew he would never take me to a theatre, and it was no use trying to give him the bag then, for someone would have been bound to have seen me. But when the perch broke, and such a chance offered, I do think I should have been a regular clodpole not to have seized it! And now—now I haven’t a meg, and it is all for nothing! But one thing issure!—I won’t go tamely home! If I can’t get to London, but very likely I shall think of a way to do so, I shall make for the coast, and sign on a barque as ship’s boy. If there had been any pirates left I should have done that rather even than have gone to London. Though I would like to see the sights, and kick up some larks,” he added wistfully.

“Don’t despair!” said Gilly, much entertained by this ingenuous history. “Perhaps we can contrive that you shall go there.”

An eager face was turned towards him. “Oh, sir, do you think I might indeed? But how?”

“Well, we will think about that presently,” promised the Duke, emerging from the lane on to the Hitchin road. “First, however, we must lay a piece of steak to that eye of yours.”

“Sir, you are a regular Trojan!” Tom said, in a rush of gratitude. “I beg your pardon for not being civil to you at first! I thought you was bound to be like all the rest, jawing and moralizing, but I see you are a bang-up person, and I do not at all mind telling you what my name is! It’s Mamble, Thomas Mamble. Pa is an ironmaster, and we live just outside Kettering. Where do you live, sir?”

“Sometimes in the country, sometimes in London.”

“I wish we did so!” Tom said enviously. “I have never been south of Kettering until they sent me to Worthing. I had the measles, you know, and the doctor said I should go there. I wish it had been Brighton! That would have been something like! Only not with old Snape. You can have no notion what it is like, sir, being Pa’s only son! They will not leave me alone for a minute, nor let me do the least thing I like, and everything is wretched beyond bearing!”

“But I know exactly what it is like,” Gilly said. “If I did not, I suppose I should have been just like all the rest, and should have handed you back to your tutor.”

“You will not!” Tom cried, in swift alarm.

Gilly smiled at him. “No, not quite immediately! But I think you must go back to your father in the end, you know. I daresay he is very much attached to you, and you will not like to cause him too much anxiety.”

“N-no,” agreed Tom rather grudgingly. “Of course I shall have to return, but I won’t do so until I have been to London! That would be worth anything! He will be in one of his grand fusses, I suppose, and I shall catch it when I do go back, but—”

“You might not,” the Duke said.

“You do not know Pa, sir!” replied Tom feelingly. “Or Snape!”

“Very true, but it Is possible that if he knows you have been my guest, and if I meet your papa, and talk to him, he may not, after all, be so very angry with you.”

Tom surveyed him doubtfully. “Well, I think he will be,” he said. “I don’t care, mind you, for I can stand a lick or two, but Pa is the biggest ironmaster in all our set, and as rich as—as Crassus, and he has the deuce of a temper! And he is for ever wanting to bring me up a gentleman, and he won’t have me do anything vulgar and jolly, or know the out-and-out fellows in Kettering, and he is bound to be in a rage over this!”

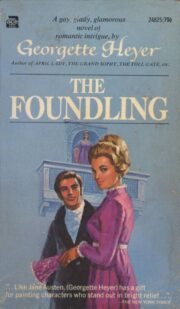

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.