“Perhaps the Runners is after him,” said the waiter. “He’s killed his man in a bloody duel, that’s very likely what he’s done, and he’s a-hiding of hisself.”

“Gammon!” said the boots scornfully. “He no more killed no one in no duel than a babe unborn!”

“Maybe there’s a fastener going to be served on him,” said the waiter doubtfully. “Though he do seem to be a well-breeched cove as isn’t likely to have got into debt.”

“No, he ain’t!” retorted the boots. “He come here on the stage, and he wouldn’t have done that if he hadn’t run aground. Swallowed a spider, that’s what he’s done. Missus ought to make him show his blunt, but she’s taken one of her fancies to him, and likely hell chouse her out of his reckoning.”

“He don’t look like a downy one to me,” objected the waiter. “And if he’d swallowed a spider he wouldn’t have handed me a fore-coachwheel only for asking of silly questions for him, which he did do.”

“What’s a half-crown to the likes of him?” said the boots disdainfully, but he was impressed by this proof of open-handedness in the Duke, and made up his mind to give his top-boots an extra polish before carrying them upstairs.

When he had partaken of breakfast, the Duke picked up his hat, and sallied forth to find the post-receiving office, where he enquired the direction of one Mr. Liversedge. The clerk said that he did not seem to know the name, and he rather thought he had handed a letter or two to a gentleman calling himself that, or something like it; but he declined to admit any knowledge of the Bird in Hand. No deliveries were made by the Post Office to any such hostelry, and if it existed at all, which he seemed loftily to doubt, it was possibly a common alehouse outside the town, such as would not be frequented by literate persons.

The Duke then bethought him of the market, and made his way there. It was the scene of considerable bustle and business, and in the excitement of watching a young bull, which seemed to have escaped from its tether, being rounded up; six pigs knocked down to a farmer in a red waistcoat; and a large gander putting to rout two small boys and a mongrel cur, he rather forgot the object in view. But when he had been strolling about the market-place for some time, he remembered it, and he asked a man who was meditating profoundly over some fine cabbages whether he knew where the Bird in Hand was to be found. The man withdrew his mind from the cabbages reluctantly, and after considering the Duke for a time, said simply: “You’ll be meaning the Bird and Bush.”

The Duke received very much the same answer from the next five people whom he questioned, but the sixth, a jolly-looking farmer with a striped waistcoat and leggings, said: “Why, sir, whatever would the likes of you be wanting with sich a place as that?”

“Do you know it?” asked the Duke, who had begun to think that Mr. Liversedge had been mistaken in his own direction.

“Not to say know it,” responded the farmer. “It ain’t the sort of place I’d go to, and what’s more, unless I’m much mistook, it ain’t the sort of place you’d go to either. For it ain’t got a good name, sir, and if you’ll take my advice, asking your pardon if not wished for, you won’t go next or nigh it.”

The Duke looked such an innocent enquiry that the farmer became fatherly in his manner, and recommended him to keep out of bad company. He said that if he were to call the Bird in Hand a regular thieves’ ken he wouldn’t be telling any lies, and added if it was plucking the Duke was after there were those whom he would very likely meet at the Bird in Hand who would leave him without a feather to fly with. He had to be coaxed to divulge the locality of the inn, and finally did so with a heavy sigh, and a warning that he would not be held responsible for whatever ill might come of it. “It’s betwixt and between Norton and Arlesey,” he said, “a matter of three or four miles from here, more, if you was to go by the pike road till you come to the road as leads to Shefford, and turn down it. But if you’re set on going there’s a lane which’ll take you right past it, and it goes by way of Norton, off the Hitchin road.”

Armed with this information, the Duke returned to the White Horse and sought out Mrs. Appleby, and asked her if she knew where he could hire a gig, or a riding-horse. It then transpired that if only he had told her earlier that he would be wanting a gig he could have had hers, and with pleasure, and old Mrs. Fawley, to whom she had lent it, might have gone to visit her daughter any other day, and not a mite of difference which. However, when she heard that the Duke only wished to drive quite a short distance, her brow cleared, and she said that if it should not be too late for him the gig was bound to be back in the stables by four o’clock, and could very well be taken out again. The Duke thanked her, and accepted this offer. She then firmly sat him down to a luncheon of cold meat, which he did not in the least want, and did her best to persuade him to let the waiter fetch up some porter, a very strengthening drink which would set him up rarely. But the Duke hated porter, and was resolute in declining.

Owing to old Mrs. Fawley’s inability to keep punctual hours, it was nearly five o’clock before the gig was returned to its owner; but the Duke thought that he would have time to reach the Bird in Hand, and to return again before darkness fell, and he decided not to postpone his visit to Mr. Liversedge. He naturally did not inform Mrs. Appleby of his destination, being reasonably sure, from what he had learned from his market-acquaintance, that she would do what lay in her power to restrain him from venturing to such a haunt of vice. It did not seem likely, in view of Mr. Liversedge’s declared requirements, that he stood in much danger of being robbed of the money in his pockets, or in any way molested, but he took the precaution of leaving the greater part of his money locked up in his chest of drawers; and he loaded one of his new duelling-pistols, and slipped it into his pocket. Thus armed, and having acquainted himself more particularly with the way to Arlesey, he mounted on to the gig, and set off at the sedate trot favoured by the stout cob between the shafts.

It was not long before he came to the lane leading from the Hitchin pike-road. He turned into this, but was soon obliged to allow the cob to slacken his pace to a walk, since the lane, once past the village of Norton, dwindled rapidly into something little better than a cart-track, and was pitted with deep holes. It was also excessively muddy; and he was forced continually to dodge unlopped branches of the nut-trees which bordered it. He met no other vehicles, which was just as well, since the track was too narrow to allow of two vehicles being abreast, and the only human being he saw was a well-grown schoolboy at the hobbledehoy stage, who came into view as he rounded the fifth bend, and splashed through a more than usually large pond of stagnant water.

He did not pay much heed to the boy at first, but as he drew towards him he noticed that he seemed to be in trouble, stumbling along in an uncertain way, as though he were ill, or the worse for drink. Then, as he came almost abreast of him, he saw that the lad, who was dressed in good but shockingly mired clothes, and seemed to have lost his hat, was extremely pale, and had a black eye. He drew up, his quick compassion stirred, and as he did so the boy’s uncertain feet tripped in a rut, and he fell headlong.

The Duke jumped down from the gig, and bent over him, saying in his soft voice: “I am afraid you are not very well: can I help you?”

The boy looked up, blinking at him in a bemused fashion, and the Duke perceived that in spite of his lusty limbs he was little more than a child. “I don’t know,” he said thickly. They took all my money. I fought them, but there were two, and—and I think they hit me on the head. Oh, I feel so sick!”

In proof of this statement, he suddenly retched, and was very sick. The Duke supported him while the paroxysm lasted, and then wiped his face with his handkerchief. “Poor boy!” he said. “There, you will be better now! Where do you live? I will take you to your home.”

The boy, who was leaning limply against his shoulder, stiffened a little at this, and said in a gruff way: “I’m not going home. Besides, it isn’t here. I shall do very well. Don’t trouble—pray!”

“But where is your home?” Gilly asked.

“I won’t say.”

This was uttered in rather a belligerent tone, which caused Gilly to ask: “Have you run away, perhaps?”

The boy was silent, and made an effort to scramble to his feet, thrusting the Duke away.

“I beg your pardon!” Gilly said, smiling. “I should know better than to ask you such awkward questions, for people have been doing the same to me all my life. We will not talk about your home, and you shan’t tell me more than you care to. But would you not like to get up into my gig, and let me drive you wherever it is you are making for?”

There was another silence, while the boy made an ineffectual attempt to brush the mud from his pantaloons. His round, freckled face was still very pale, and his mouth had a sullen pout. He cast a suspicious, sidelong look at the Duke, and sniffed, and rubbed his nose. “They took all my money,” he repeated. “I don’t know what to do, but I won’t go home!” He ended on a gulping sob that betrayed his youth, flushed hotly, and glared at the Duke.

Gilly was far too tactful to notice that unmanly sob. He said cheerfully: “Well, to be sure, it is very hard to decide on what is best to be done without having time to reflect. Have you friends in the neighbourhood to whom I could take you?”

“No,” muttered the boy. He added grudgingly: “Sir.”

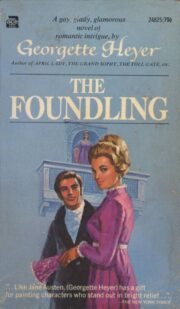

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.